Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Tuesday, 8 February 2022 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa

Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa

Central Bank Governor Nivard Cabraal

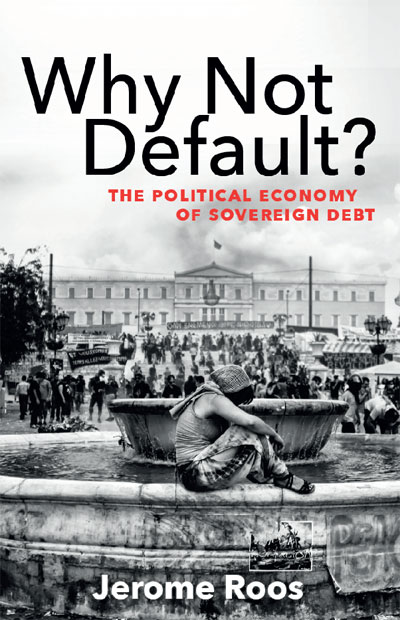

Why Not Default: The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt’ author Jerome Roos

|

Sri Lanka may be on the verge of defaulting on its sovereign debt. Some economists are even proposing default as the way forward. To understand the consequences of default for the country, we engage with a scholar who provides a novel perspective. London School of Economics academic Jerome Roos’ book, ‘Why Not Default: The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt’ (Princeton University Press, 2019), presents an important set of ideas about what default potentially means for countries that face sovereign debt crises.

Sri Lanka may be on the verge of defaulting on its sovereign debt. Some economists are even proposing default as the way forward. To understand the consequences of default for the country, we engage with a scholar who provides a novel perspective. London School of Economics academic Jerome Roos’ book, ‘Why Not Default: The Political Economy of Sovereign Debt’ (Princeton University Press, 2019), presents an important set of ideas about what default potentially means for countries that face sovereign debt crises.

Using historical and comparative examples, Roos outlines the critical mechanisms by which countries either avoid default or embark on an alternative path by choosing default. More generally, as Roos argues, “It has become clear that future scholarship on sovereign debt— and on global finance more generally—can no longer bypass its social and political dimensions” (p.18).

Roos admits that the focus of his book is not on the internal politics within the debtor countries themselves (p.77). But he provides a useful framework for grasping the dynamic role of power in understanding why countries choose to default, or not. Embedded within his perspective is the assumption that if a left-leaning pro-default coalition is strong enough, it can reject the onerous conditions offered in a bailout agreement by a lender of last resort, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). It can potentially weather the short-term shocks of default to pursue a more sustainable economic strategy. In contrast, most countries which must undergo debt restructuring to avoid default must sacrifice the livelihoods of their citizens for the interests of creditors.

From the perspective of the current crisis in Sri Lanka, we see that the choice has apparently been flipped on its head. Now the people advocating default are predominantly right-wing neoliberal experts, as opposed to an intransigent Government that claims to be charting a new path. Rather than a rejection of austerity, default is considered another path to debt restructuring, which involves forcing the public to absorb the costs of private speculation and extraction. Nevertheless, even though Roos’ political assumptions are complicated by the specific axis along which the current Sri Lankan debate is polarised, he helps us understand the general consequences of default.

From the perspective of the current crisis in Sri Lanka, we see that the choice has apparently been flipped on its head. Now the people advocating default are predominantly right-wing neoliberal experts, as opposed to an intransigent Government that claims to be charting a new path

Thus, for those who see default as a reasonable option, we must instead outline the factors that would shape Sri Lanka’s own approach to default. These would define its politics and distributional consequences. Applying Roos’ framework, we argue that default cannot be understood in progressive terms in our current context. Rather, it must be recognised as another way in which the elites within the debtor country—in our case, Sri Lanka—are attempting to reconstitute their effective control over the country’s economy.

|

The theoretical framework

Roos begins his book by exploring, from a theoretical point of view, why countries in general tend to avoid default, in contrast to the previous historical epoch, before the 1980s, when default was a much more frequent occurrence. As he argues, because of its increased structural power, finance capital has a tremendous degree of leverage over the policies of debtor countries. As he puts it, “We can define structural power as the capacity to withhold something upon which another depends” (p.58). Debtor countries rely not only on access to international capital markets to try and rollover debt, but also basic facilities such as trade credit (p.16). Accordingly, Roos’ point is that finance capital defines the rules of the game, making it significantly more likely that debtor countries will comply with restructuring, as opposed to trying to chart an independent course by defaulting.

Roos identifies three main reasons for why cases of default in recent history are extremely rare: 1) the immense concentration of international creditors, 2) the interlocking of lenders of last resort, especially the IMF, with debtor governments, and, as he puts it, 3) “the growing dependence of the capitalist state—and the capitalist economy more generally—on private credit” (p. 12).

Roos’ point is that the third factor especially entrenches the shared interests of the elites in the creditor and debtor countries. Elites within debtor countries themselves ensure compliance with the terms of a bailout agreement because they are most likely to lose out in a default scenario in which the government rejects austerity as a condition of debt restructuring. Moreover, these forces are more likely to obtain a better deal regarding terms of credit than a progressive pro-default coalition that opposes austerity (p.15).

|

Historical and comparative examples

Historical and comparative examples

The ways in which these dynamics play out in each historical situation is very different. For example, in Sri Lanka’s case as mentioned earlier, it is now sections of the economic establishment that are promoting default for their own ulterior purposes. Nevertheless, the strength of Roos’ framework is that it is supple enough to handle these divergent outcomes, while exploring the potential consequences for debtor countries themselves. As he points out in his analysis of Argentina, it is the “exception that proves the rule” (p.174) because of the breakdown of the three enforcement mechanisms mentioned above.

In Argentina’s case, by 2001, the country was experiencing massive popular protests. Working people and middle classes hit hardest by crisis opposed the elite’s attempts to impose austerity. Meanwhile, the creditors holding Argentinian debt changed in composition. Institutional buyers exited the market while retail investors purchased more debt (p.180). This centripetal dynamic resulted in the fragmentation of the creditors, undermining their leverage. Finally, for its own geopolitical reasons, the US accommodated the left-leaning Kirchner government that eventually took power and opposed austerity (p.214). These dynamic variables enabled the country to pursue default as a viable option.

The same convergence of factors did not apply in Roos’ other two recent contemporary examples of Mexico, during the 1980s, and Greece, during the 2010s. For example, in the latter case, during Greece’s debt crisis, there were also massive mobilisations against austerity imposed by debt restructuring. In the referendum of 2015, the Greek people even voted against terms for a bailout agreement promoted by the European Troika (the European Commission, European Central Bank, and IMF).

But Greece’s own left-leaning government, Syriza, ultimately complied with the terms of the agreement. The lenders of last resort, the Troika, remained staunch in their position against any breach of the agreement (p.275). Syriza, too, was unwilling to grapple with the ultimate implications of default, which would have potentially meant abandoning the Euro.

Default and devastation

Roos concludes that any long-term transformation of the global debt structure would require “mass social mobilisations” within countries in the global North and South (pp.309). He also mentions in brief other potential strategies that debtor governments themselves can adopt, such as exemptions for pensioners and other smaller categories of investors, to shield them from the full effects of default (p.306).

But, as Roos makes clear from the outset, default can be a devastating process. We quote him at length below to describe the dynamics following default:

“The spillover costs of default would initially spread through the transmission belt of the financial sector, with a default on foreign creditors likely to provoke capital flight, a stock market crash, and a collapse of domestic banks and pension funds. But given the centrality of finance to contemporary capitalism, the consequences would quickly ripple throughout the wider economy, risking massive social dislocation in the process.

“Exporters and importers would no longer be able to obtain trade credit, causing shortages of crucial consumables and industrial inputs; depositors would fear the safety and value of their savings and would likely instigate a bank run and mass capital flight, making the imposition of unpopular capital controls all but inevitable; producers would no longer be able to attract foreign or domestic investment and would start laying off workers in droves; households would see unemployment skyrocket while no longer being able to obtain credit for consumption, as a result of which aggregate demand would dry up—in sum, the bankruptcy of the state would risk provoking the bankruptcy of large parts of the domestic economy, with devastating social consequences (at least in the short term) and potentially grave implications for the government’s capacity to legitimise itself in the eyes of its citizens.” (p.16)

Thus, even to consider default, the debtor government must be incredibly clear-eyed about the risks. It must be capable of managing massive short-term disruption. This approach also assumes that the government has a plan to successfully transform the country’s economy in the long run, to move away from continued dependence on debt.

|

Politics of default in Sri Lanka

The differences between the examples outlined above, especially Argentina, and Sri Lanka should be clear. Whereas in the case of the former, default was proposed by a left-leaning government that came to power through massive popular mobilisation opposing austerity, default is now being bandied about as a solution by our mostly right-wing economic experts, ostensibly as a way of keeping “food on the table.”

The reality, however, is that not only are these experts unwilling to tolerate a rupture with austerity, but they also do not see default as implying divergence from continued dependence on debt. In fact, the debate among experts themselves right now is what is ultimately the fastest way for Sri Lanka to regain access to international capital markets!

Finally, they have not evinced the slightest bit of awareness of the vast range of challenges that would make default, and debt restructuring in general, a brutal process for Sri Lanka in the current moment. For example, as Roos himself puts it, many trends in the global economy had to converge in favour of Argentina for the country to navigate the challenges of default, such as the growth of its trade surplus because of a boom in commodity exports.

In contrast, Sri Lanka is staring down the barrel of the gun with the US Federal Reserve likely to raise interest rates soon. These manoeuvres within the heart of global capitalism will further isolate Sri Lanka from external capital and put massive pressure on the country’s Government to conform to an agreement that favours creditors above all else.

While our experts talk about putting food on the table, the reality is that they aren’t even considering, much less publicising, the real structural reforms that would be necessary to ensure ordinary people’s survival. As mentioned elsewhere, these include cutting down on the import bill by prioritising essential imports, distributing subsidies to cover the effective increase in food prices, and investing in domestic food production.

Progressive positions

Although Roos considers what would make a progressive pro-default coalition successful, we can invert the focus of his argument. We must consider the range of factors that would likely make debt restructuring, either before or after default, a far more painful process for ordinary Sri Lankans under the current circumstances. Progressives seriously pondering default, or debt restructuring in general, must comprehend the array of forces stacked against Sri Lanka. They must reckon with the political implications of an IMF-led reform process that this choice would engender.

Despite whatever progressive veneer the IMF may now try to adopt, the reality is that a bailout agreement would rule out import restrictions. The latter contravene the core ideological assumptions of that institution. One doesn’t need to be a starry-eyed leftist to realise that the IMF is shaped by the interests of powerful creditor countries. And as Roos also points out, what is ultimately at stake in any default or debt restructuring is the degree of democratic control a country has over its own policies (p.80; p.301).

By embedding itself further within the IMF-creditor nexus, Sri Lanka would be sacrificing whatever little control it has left, and accepting whatever solution is proposed by the powers that be. In this context, the current Government is proceeding along the parallel path of subordinating itself to regional and global powers. It is mulling over the strategic assets it can pawn, while attempting to manage the political fallout.

In contrast, if we are serious about getting out of this mess altogether, we must be honest about our goals and realistic about the strategies to achieve them, especially considering the extent to which Sri Lanka’s economy continues to be characterised by overwhelming dependence on the external sector. Only a comprehensive alternative to both the Government’s dilettantish policies and austerity-driven debt restructuring—whether before or after default—will enable Sri Lanka to regain control of its economy, thereby ensuring that its people can survive the current economic crisis and thrive in the long run. At the heart of the political question about default and restructuring debt is who takes on the social and economic burden of decades of extraction through sovereign debt by global finance capital and its comprador elite in Sri Lanka. Our firm commitment is that it should not be the working people. How about you?

(Devaka Gunawardena is an independent researcher who holds a PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles and Ahilan Kadirgamar is a Senior Lecturer, University of Jaffna.)