Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Monday, 15 February 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

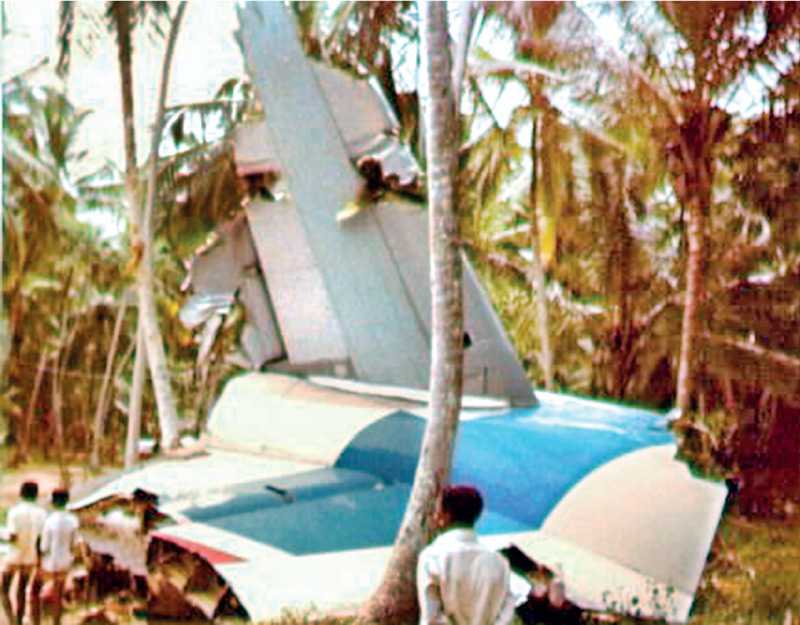

The crash site thronged by spectators – Photo DP collection

The tragic crash of Flight LL001, a Douglas DC-8-63CF operated by Icelandic Airlines and chartered by Garuda Indonesia, in November 1978 sent shock waves through Sri Lanka. The island was just emerging from a long period of self-imposed isolation. In November 1978, when the accident occurred, the country still did not have any TV stations.

The tragic crash of Flight LL001, a Douglas DC-8-63CF operated by Icelandic Airlines and chartered by Garuda Indonesia, in November 1978 sent shock waves through Sri Lanka. The island was just emerging from a long period of self-imposed isolation. In November 1978, when the accident occurred, the country still did not have any TV stations.

Radio news bulletins announced details of the accident, and the public turned out in their hundreds at the crash site, making crowd control a major challenge to authorities who had no experience in dealing with this sort of disaster. The earlier crash of the Martinair flight (in 1974) had occurred in a remote part of Sri Lanka that was hard to access, but this latest accident was in close proximity to the airport, thus attracting hordes of ‘rubber-necking’ sightseers.

Poor infrastructure

Many years of relative isolation had also resulted in much of the country’s infrastructure being in a sorry state. The airports were no exception, but lessons learned from the Martinair crash produced some improvements. However, these too had proved to be lacking, as some vital equipment (such as the Approach Lighting System – ALS) was not working on the night of the Icelandic crash, while the electrical power supply to the airport was best described as ‘erratic’.

The malaise had spread to the national carrier Air Ceylon, once a pioneering airline now reduced to a shadow of its former self. Founded in 1947, the airline had never achieved its potential due to inept management and government policies that did not allow the economy to expand. A Presidential Commission to investigate its shortcomings had led to a damning report published in July 1978. The situation was so bad that the government had decided to let Air Ceylon wither away, and a fresh start made by setting up a new company named Air Lanka as the national carrier.

The accident investigation

Aircraft accidents are investigated closely; in order to not only ascertain what happened, but also to learn from any shortcomings so as to prevent similar occurrences in the future. A multi-disciplinary team with representatives from the aircraft manufacturer, the operator, the airline, and the country where it occurred, work together to determine the facts and make recommendations for the future.

In this case the Government of Sri Lanka appointed a former Supreme Court judge, Justice Siva Supramaniam to inquire into “...the causes and circumstances... (of the accident) …”, “To consider whether any degree of responsibility … may be attributed to any one person” and “To recommend what steps, if any, should be taken to ensure the avoidance of similar accidents in the future.”i

At the time Sri Lanka was still functioning under the Air Navigation Regulations last amended 22 years earlier, in 1956. There were no professional aircraft accident investigators in the country, and expertise was lacking in many disciplines essential for conducting such an in-depth inquiry.

The basic facts

Icelandic LL001 had been on a fairly routine instrument approach to Katunayake airport on what might be described as ‘a dark and stormy night’, but weather conditions were not extreme. The crew had sighted the runway well before the Minimum Descent Altitude (MDA), as is evident from conversation on the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), one of the two components of the so-called ‘black box’ that record vital information on every commercial flight.

Yet, despite being ‘visual’, the aircraft deviated from the optimal 3° gradient that is the Glideslope (GS) prescribed by the Instrument Landing System (ILS; the radio signal that enables avoidance of obstacles on the ground during the final approach). First, the pilots climbed a little above the GS, then descended well below itii. At that stage the sound of rain could be heard on the CVR, and the crew were evidently seeing lightning flashes, a sure sign that they were in close proximity to a thunderstorm.

Shortly thereafter the aircraft descended well below the GS. The First Officer called out, “You are red on the VASI” (Visual Approach Slope Indicator), suggesting that they could see the runway lights, and knew they were too low.

The Captain responded with “Max Climb”, but it was too late. The aircraft impacted coconut trees, the tallest of which stood 163 feet above the runway altitude.

A contentious process

The final report of the Commission of Inquiry is typically an unemotional document. But reading between the lines of the bland prose, and from anecdotal evidence given by the few remaining people who were involved, this investigation was a contentious affair.

A delegation from Icelandic Airlines was present, and they appear to have been intent on protecting their dead colleagues from damage to their professional reputations. They seem to have insisted that the glideslope (vertical) portion of the ILS was “bent” due to poor maintenanceiii. Several complaints from other airlines stating that the ILS was “tripping”, and “unreliable”iv were produced as evidence of culpability on the part of the airport.

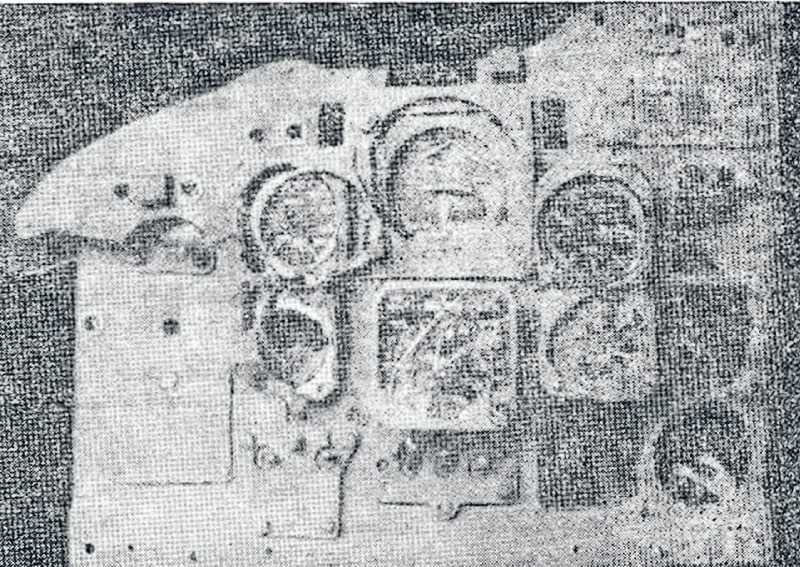

Justice Supramaniam appears to have gone to great lengths to educate himself on the technical details of the navigation equipment and instruments on the flight deck of the DC-8-63. Part of the Captain’s instrument panel was recovered and a photograph of it (see given picture) appears in the final reportv.

The newly appointed Executive Chairman of Air Lanka, (the late) Captain S. Rakkitha Wickramanayake, himself an experienced, senior pilot, also testified at the Commission. He categorically stated that if the approach had been discontinued at the correct altitude, the aircraft should not have impacted a tree as low as 163 feet above the runway. He also stated that if the GS was “bent” and it gave an inappropriate ‘fly down’ command, if he was the flying pilot he would have “disregard(ed) it”vi.

Probable cause

The final report stated that the probable cause of the accident was “… the flight crew’s failure to conform to the laid-down approach procedures.”

While fixing the blame squarely on the crew, the report also mentioned, in the last comment of Section XV, “Contributing to the accident was the fact that there was a down-draught of the wind which probably rendered recovery more difficultvii…”

Windshear and micro-bursts

It is important to note that this accident occurred more than 40 years ago, when aviation was still a relatively risky undertaking. The industry has improved its safety rate exponentially since then. The ‘black boxes’ recovered from LL001 were of the older analogue type, with less information provided than the newer digital flight recorders then being introduced.

The dangers associated with thunderstorms, though evident, were not fully understood in 1979. It was only when Delta Airlines Flight 191, a Lockheed L-1011 TriStar (the safest aircraft of its time and equipped with digital flight data recorders) had a fatal encounter with a thunderstorm in Dallas, Texas in 1985, that the destructive power of a thunderstorm was fully revealed. That accident, which resulted in 134 fatalities, was attributed to an “encounter at low altitude with a microburst-induced severe windshear, from a rapidly developing thunderstorm located on the final approach courseviii.” A ‘microburst’ is defined as ‘a localised column of sinking air or downdraft within a thunderstorm’ix. This was a little-understood phenomenon in 1979.

Did LL-001 encounter a microburst?

A microburst close to the ground just ahead of an aircraft on approach would cause the airplane to first encounter a headwind that would cause it to climb. If the crew did not recognise what they were experiencing and abandon the approach, they would then encounter a severe downdraft, followed by an increasing tailwind from which it may not be possible to recover in close proximity to the ground. With the benefit of hindsight it would appear that the crew of Icelandic Airlines Flight LL001 encountered a thunderstorm and a severe microburst while on approach to Katunayake airport at night, causing a loss of altitude sufficient to impact trees in the vicinity of the field.

This is easy to discuss on the ground, but in the cockpit of an aircraft, on a dark and stormy night on approach to an unfamiliar airport, such clues are easy to miss.

The aftermath

The findings of the Commission and the publicity surrounding them led to many changes in Sri Lanka. Civil Aviation Regulations were amended to comply with international norms and the infrastructure was updated. Thankfully, since then there has not been a major accident involving a passenger aircraft in the country.

Footnotes:

iReport of the Commission of Inquiry into Icelandic Airlines aircraft TF-FLA Page 1

iiIbid Annex IV Page 43

iiiIbid Page 19

ivIbid Page 25

vIbid Annexe XIV Page 77

viIbid Page 26

viiIbid Section XV Page 33

viiiNTSB/AAR-86/05

ixUS National Weather Service definition

The tail section of the doomed airliner – Photo DP collection

The Captain’s instrument panel