Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday, 9 April 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“The global syndemic represents the paramount health challenge for humans, the environment, and our planet in the 21st Century” – The Lancet

For the first time in recorded history, bacteria, viruses and other infectious agents do not cause the majority of deaths or disability in any region of the world. Deaths from malaria, tuberculosis and diarrheal diseases have fallen more than 25% each since 2003. In 1950, there were nearly 100 countries, including almost everyone in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Southeast Asia, where at least one out of five children died before their fifth birthday. Today, there are none. The average life expectancy at birth in developing countries has risen to 70 years.

But the news is not all good. In the past, gains in longevity went hand in hand with broader improvements in health – care systems, governance, and infrastructure. That meant the by-products of better health – agrowing young work force, less deadly cities and a shift in countries’ health care needs to the problems of older people - were sources of wider prosperity and inclusion. Today, improvements in health are driven more by targeted medical interventions and international aid than by general development.

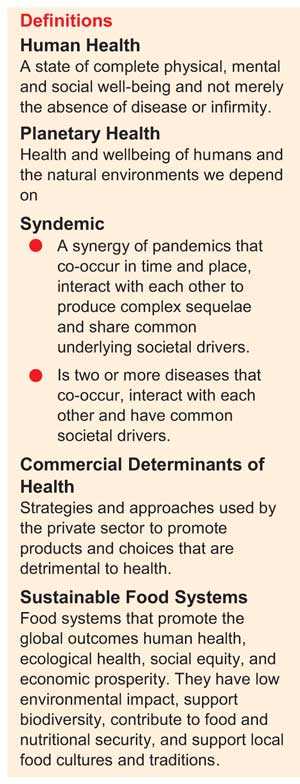

Human health has come to be viewed in terms of the mere absence of diseases or the successful or unsuccessful treatment/control of it. This is of course contrary to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health. Consequently, disease care has come to be accepted and synonymous with health care.

This misinterpretation of the definition of health is the fundamental cause of the rise of the epidemic of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) globally. Multidisciplinary research clearly shows that this is a manifestation of the global economic system that currently prioritises wealth creation over health creation. Put simply, the NCD epidemic is to a very large extent man made for the benefit of wealth creation. In economic terms, this situation represents a clear case of commercial success (wealthy corporations) but market failure (negative human health and environmental outcomes).

There can be little doubt of the reality of human-induced and sustained climate change. Scientific consensus of the link between Greenhouse Gas emissions (GHGs) and climate change only grows stronger and the effects – oncea hypothetical risk for the future – arealready becoming a clear and present danger in the form of rising seas levels, increasingly unpredictable weather patterns and extreme weather events.

Estimates of future economic costs of climate change are 5-10% of the world’s GDP, with costs in low-income countries that may exceed 10% of their GDP. The bulk of the human cost of climate change will also fall on low-income countries that are less able to cope and who have contributed least to the problem.

The net impact of health care (as opposed to disease care) on society is overwhelmingly positive. In today’s context of almost total disease care (as opposed to health care) we must recognize that there are costs as well as benefits to it. The concept of ‘value-based health care’ – wherehealth outcomes are weighed against the cost of securing them-has spread around the world in recent years. In reality though political, business (and at times even health) leaders tend to calculate cost only from an economic perspective, ignoring social and environmental externalities such as greenhouse gas emission, loss of biodiversity, unsustainable agricultural practices (including financial incentives in the form of subsides to beef, dairy, sugar, corn, rice and wheat) and poor urban planning (unhealthy cities).

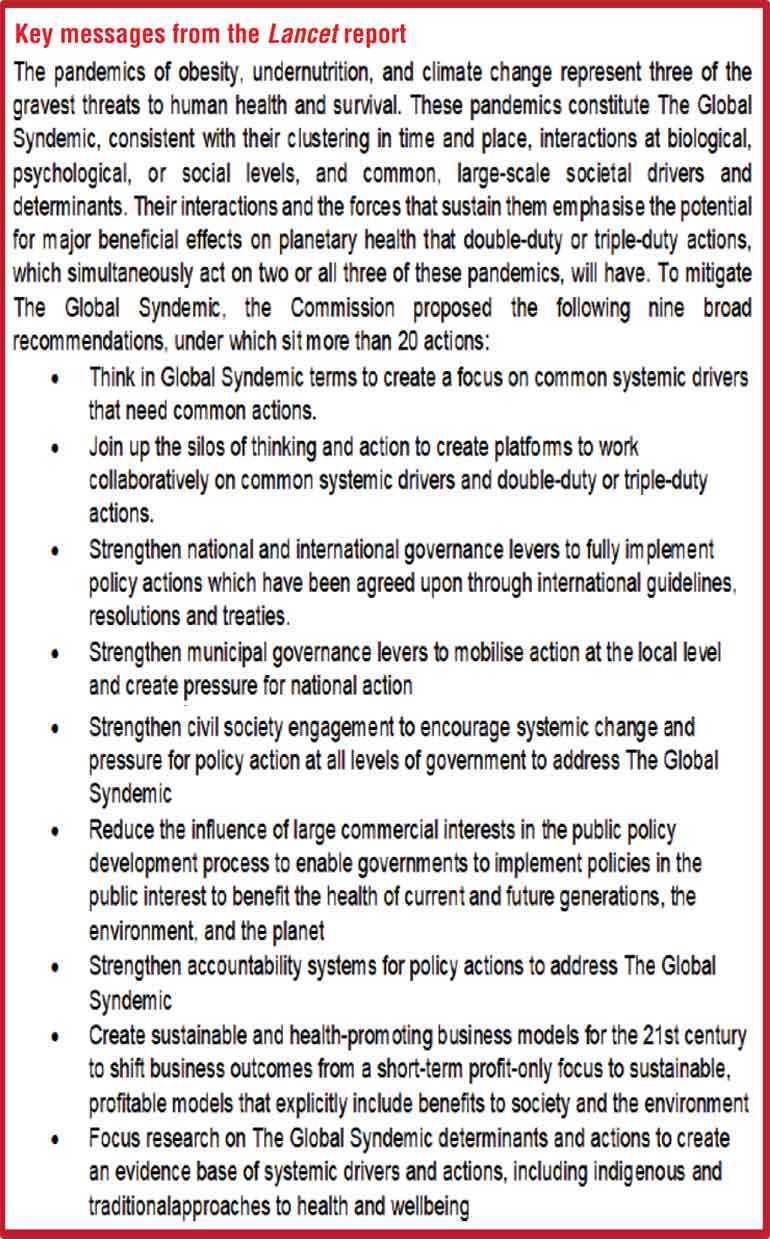

In this context The Lancet Commission report on ‘The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition and Climate Change’ provides a welcome scientific analysis by a team of multidisciplinary international experts who lays forth the evidence as to why every one of us must have some understanding of the global syndemic. More importantly the report sets a framework within which each one of us are duty bound to contribute towards for the future sake of planetary and human welfare, to achieve the outcome of health with wealth!

The Lancet Commission report started out as a Commission on Obesity and changed direction during the three years of work by the commissioners, to put obesity into the much wider context of the global syndemic of obesity, under nutrition and climate change. The authors bravely reject the temptation to summarise the problems of, and solutions to, global obesity alone. They also leave it to others to explain what we know and don’t know about nutrition and obesity and related metabolic disorders.

The report takes the concept of the syndemic a step further and applies it to go beyond individual diseases, in effect shifting focus from diseases to people and shifting focus from disease care towards health care (both human and planetary health). It identifies in an evidence-based manner the deep systemic problems which are responsible for causing and sustaining the global syndemic.

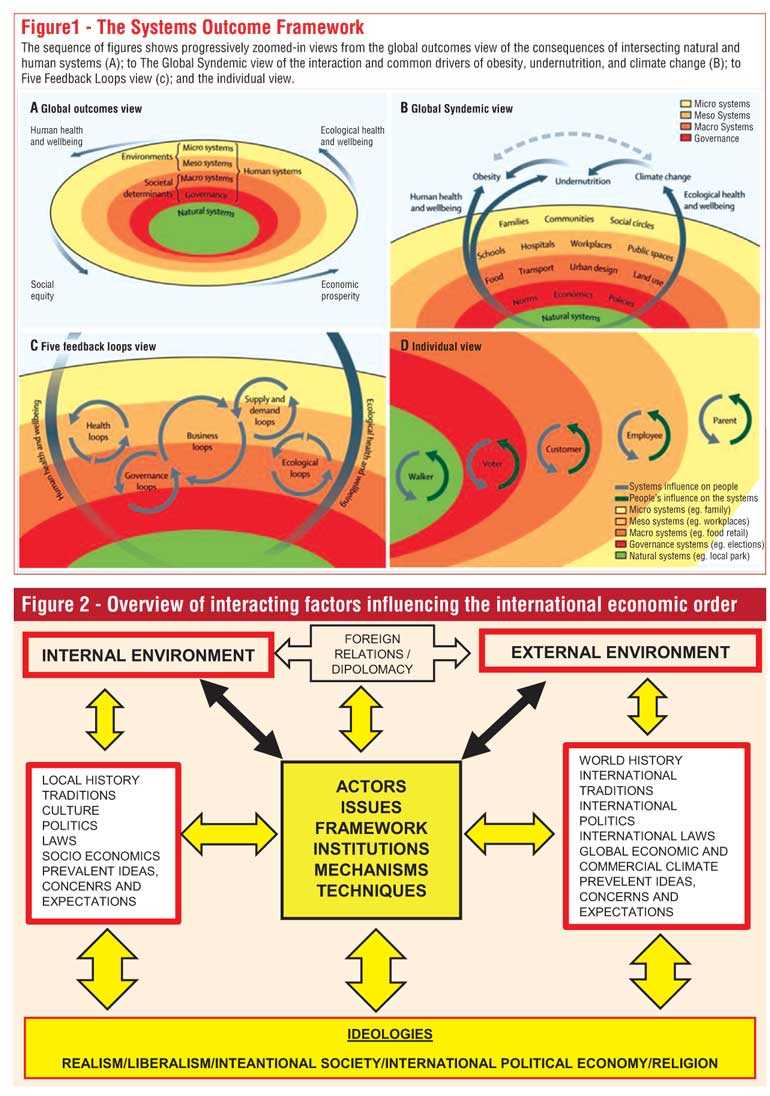

Prominent among them are the global industrial system that spurs homogeneity in production and consumption, externalises harms to health, social cohesion and environment and prizes cheap food. It analyses the multi-layered and multidimensional array of factors that are implicated in the dramatic global rise of obesity, under nutrition and climate change (Fig.1).

The Commission lobs a comprehensive and fair critique at the outcomes of the international economic order. At a time of inward-looking national governments, emerging populist movements in many countries and misguided distrust of data and science, strong international efforts and voices are needed to build bridges between these conflicting scenarios while respecting the divergent ideas, concerns and expectations emanating from this diversity (Fig. 2).

But there is a massive lacuna in this regards, primarily due to policy inertia. The policy inertia of course stems from the reluctance of political decision-makers to implement effective policies, powerful opposition by vested commercial interests, and insufficient demand for change by the public and civil society.

The Commission suggests ways to harness the power of politics and economics to find solutions to the global syndemic. The report is full of good and necessary ideas but here’s where advocacy needs to be audience-appropriate and the economic figures presented in the report can be very helpful.

The paradoxical lack of demand for change by civil society towards improving human and planetary health is largely due to the commercial determinants of health. As noted by Dr. Margaret Chan the Immediate Past Director General of WHO “…efforts to prevent non-communicable diseases go against the business interest of powerful economic operators”. The commercial determinants of health leads to unhealthy commodities, industrial epidemics, profit-driven diseases and corporate practices harmful to health. The focus on lifestyle choices, especially in relation to marketing to children has a profound impact on the global syndemic.

In the context of commercial determinants of health, the report devotes more than adequate analysis to business models for the 21st century and reducing power imbalances and conflict of interest. In doing so it emphatically acknowledges the central role of the private sector in creating wealth, income and jobs, advancing innovation, and mobilising domestic resources.

Given the enormous size and contribution of the corporate sector globally, it is critical that corporations are included in the collective work to address major societal issues, such as the global syndemic, in ways that ensure effectiveness and accountability for their actions. There needs to be widespread recognition that current politico-economic systems and prevailing global regulatory structurers have incentivised businesses to be the engines driving the global syndemic and allowed them to prevent policy action to reduce it. In other words, the current system allows or incentivises the privatisation of profit and the socialisation of the costs of the global syndemic.

Complex social, environmental and health challenges have been addressed successfully through social change process, leading to cultural shifts in values and to public policy actions that have changed population behaviours. In this context the Commission describes among other strategies the Seven Generation Stewardship Concept of the Iroquois Indigenous people where by the current generation lives and works for the benefit of seven generations in to the future.

Our generation has the insight, evidence and opportunity to act and change path for better human and planetary health. The Lancet Commission report on ‘The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition and Climate Change’ is a start to make this happen.

The full report is available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)30310-1/fulltext.