Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Tuesday, 24 November 2020 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Australians and the world had much to celebrate. More than 26,000 Australian uniformed personnel were sent to Afghanistan to fight alongside US and allied forces against the Taliban, Al-Qaeda and other Islamist groups. Australian troops inducted into the Afghan War as allies of the US after the 9/11 attack in New York in 2001 were accused of massacring Afghan civilians. That is bad. However, the good news is that in Australia, the accused killers are not being celebrated as heroes but are being charged.

Australians and the world had much to celebrate. More than 26,000 Australian uniformed personnel were sent to Afghanistan to fight alongside US and allied forces against the Taliban, Al-Qaeda and other Islamist groups. Australian troops inducted into the Afghan War as allies of the US after the 9/11 attack in New York in 2001 were accused of massacring Afghan civilians. That is bad. However, the good news is that in Australia, the accused killers are not being celebrated as heroes but are being charged.

Australia and Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka and Australia bear nominal similarities. Our population is about 21.67 million; Australia’s is about 24.99 million. We are both democracies. Australia extended its adult suffrage to all in 1967, regardless of ethnicity. We extended our restricted suffrage to hill country Tamils much later in 2003 with the passage of ‘The Grant of Citizenship to Persons of Indian Origin Act’.

What is common now is that Sri Lankan troops and Australian troops stand accused of war crimes. But parallels end there. How we have handled war crime accusations is riddled with common features and major differences.

Handling war crimes accusations

One common feature concerns the real heroes – the whistle-blowers. Our own soldiers carried out many atrocities against LTTE cadres, with some of the information regarding these reaching the Human Rights Council through whistle-blowers. Likewise, in Afghanistan, too, it was troops who brought out the ghastly tales of what their comrades had done – new patrol members were coerced to shoot a prisoner in order to achieve his first kill, in a practice known as “blooding”, reports AFP, adding that once troops killed a six-year-old child in a house raid, and in a separate incident, a prisoner was shot dead to save space in a helicopter. The 400+ page report reveals the culture of blood-lust among Australian troops, headlined CNN.

The alleged scale of Sri Lankan killings is vastly different – more than 39 by Australians and over 40,000 by Sri Lankans, according to the UN (while the book Palmyra Fallen by Rajan Hoole, through examination of data including family size, calculates the figure at over 100,000).

Like our government, the Australian government’s first instinct was to scare those who would talk about it. Australia spent years trying to suppress whistle-blower reports, with police even investigating reporters writing about those accounts.

Likewise, in Sri Lanka, MP Imtiaz Bakeer Marker informed Parliament that the Government is preparing to arrest 200 journalists and social media activists. Moreover, just as Britain’s Channel 4 brought the cruel images into our homes, in 2017, public broadcaster ABC published the Australian allegations. In response, as AFP reports: “Australian police launched an investigation into two ABC reporters for obtaining ‘classified information’.” ABC’s Sydney headquarters were raided last year, before dropping the case. Recall our NGO people going to Geneva, and Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu and Jehan Perera getting a grilling on their return.

Good sense, however, prevailed at last in Australia. In a proper democracy, facts cannot be suppressed for too long because there is a free press. In Sri Lanka, our press is often too scared to report after what happened to Keith Noyahr and Lasantha Wickrematunge. Our press is yet to report on Australia’s crimes, a major story. Alternatively, much of our press takes a nationalist line, ridiculing those who call for justice. Not so in Australia. An inquiry was launched.

In Sri Lanka, however, the whole country seems communalist, going by recent election results. In the height of the election campaign, even the Opposition seemed to reflect the communalism of the Government in opposing war crime trials. As Sinhalese fight shy of their democratic duty to call for accountability; to Tamils, it seems that there are no good Sinhalese left. Therefore it urgently devolves on the Government to recognise the cleavage its politics is causing and reverse course.

If Sri Lanka persists in resisting accountability, it is likely that in the present rights milieu, we will ultimately be cornered and forced into trials by the world – if not soon, at least in time, or the entire human rights regime we have pushed forward with the UN would lose value as a tool of those in power.

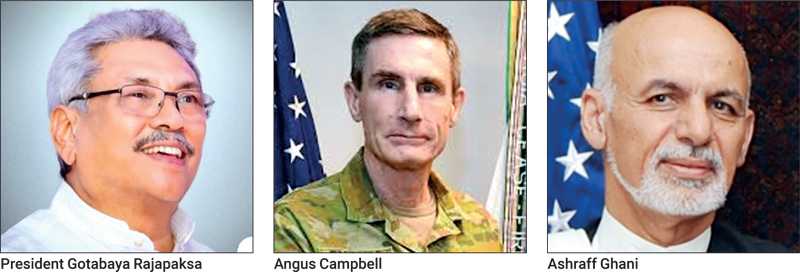

After a year-long investigation, Chief of Defence Force General Angus Campbell (Chief of Army since May 2015) on Thursday (19 November) admitted there was credible evidence that his special forces unlawfully killed at least 39 Afghan civilians, prisoners, farmers and children, recommending the matter be taken up by a prosecutor investigating alleged war crimes.

As AFP reported, Campbell announced: “Some patrols took the law into their own hands. Rules were broken, stories concocted, lies told, and prisoners killed." The pattern is all too familiar to us. Just imagine our President Gotabaya Rajapaksa or Army Commander Lt. Gen. Shavendra de Silva making similar admissions. It would transform how the populace views the State and promote reconciliation.

The office of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani stated that Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison had "expressed his deepest sorrow over the misconduct". While AFP mentions that Australian officials dispute this account, CNN does not mention the dispute and gives Prof. Ghani’s account as fact.

In this context, I met Prof. Ghani in Afghanistan during the 2017 Forum of Election Management Bodies of South Asia (FEMBOSA). We hit it off because of our shared university backgrounds. He was at the head of the table at the State dinner and asked for me to sit on his right, continuing our discussions. I had asked for a vegetarian meal and by mistake, the rice had chunks of lamb. In Buddhist Sri Lanka, I am usually given ‘vegetarian’ food with Maldive fish and my favourite fried brinjal is ruined for me. I have been in countries where I was thoughtlessly told to remove the meat and eat the rest. Prof. Ghani, however, asked for a new special dish to be brought. That is culture; multiculturalism. I believe his account, which fits with Morrison announcing the appointment of a special investigator to prosecute the alleged war crimes and Campbell recommending that Distinguished Service medals awarded to special operations forces who served in Afghanistan during 2007-2013 be revoked.

An independent panel was also set up to drive cultural and leadership changes within the armed forces. The Australian government is taking a stern view against the culprits, and is a sound example for us in Sri Lanka to emulate.

Sri Lankan mendacity

We must stop denying the massacres. Hundreds who surrendered have disappeared. The International Truth and Justice Project has listed 293 such persons. As JDS Lanka reported, in several instances, the military confirmed LTTE cadres had surrendered to the army, including in 2012 when an Army Court of Inquiry acknowledged that the military captured LTTE cadres and that 11,800 cadres had surrendered to the military. The BBC cites video evidence on the surrender it calls compelling.

Lying is so endemic to our Government that officials inured to it fail to recognise when they make ridiculous claims. When responding to an RTI request after the military had conceded accepting the LTTE-ers’ surrender, the Information Officer of the military Brigadier Sumith Atapattu stated: “LTTE members have not surrendered themselves to the Sri Lanka military during the last stages of the war, and they have handed themselves over to the Sri Lankan Government.”

Former Minister of Rehabilitation and Prisons Reforms D.E.W. Gunasekera in July 2010 admitted that he had met the ‘widows’ of top LTTE-ers V. Balakumar and Yogaratnam Yogi, who had been in the Army’s protective custody. Calling them widows, he inadvertently admitted to their husbands being dead.

And then, as the BBC reported on 20 January: “Sri Lanka's President has acknowledged for the first time that more than 20,000 people who disappeared during the country's Civil War are dead.” The conclusion on government mendacity and how the 11,800+ died dictated by common sense is inescapable.

India, the LTTE?

“What of India and the LTTE owning up to their killings?” ask those who defend our Government. Where there was real crime, the Indian army has presently carried out disciplinary inquiries. For example, as recently as September, NDTV reported that soldiers involved in a controversial encounter in which three terrorists were claimed to have been killed in Jammu and Kashmir on 18 July have been indicted by the Indian army.

After inquiry, finding that troops exceeded powers vested under the Armed Forces Special Power Act, disciplinary action followed. That is another example for Sri Lanka to emulate, sans the exoneration on appeal or a pardon after conviction, as is our template. We are naked but do not know it.

Why should India not apologise for the killings during 1987-1990? The answer is that she should for actions where criminality is undeniable. However, crimes committed in the course of military confrontations are hard to investigate, and as far as we know, neither the Indian nor the Sri Lankan army had investigative mechanisms in place then. It would have been better for everyone if they had. The LTTE was itself callous with regard to civilian welfare, and in documented instances, connived at civilian deaths for propaganda effect and recruitment.

India came at Sri Lanka’s invitation to preserve the integrity of the island and left promptly when she was betrayed by Sri Lanka and asked to leave before her job was done. Our Government, thereby, revived the LTTE and facilitated the return to war.

That brings up the question of "why I do not ask for trials against and apologies from the LTTE for its crimes pointed out by the UN and many Tamils. After the Government had killed the very people to be charged and to be asked to apologise, there is no one to be tried or to apologise.

In contrast, with persons disappeared after surrendering to the Army before witnesses and family, there is no excuse for Sri Lanka. The country will be better defended at far less expense if the human qualities of the security forces are improved with the cooperation of the UN and ICJ, and accountability mechanisms put in place.

Einstein’s thought experiment

Just imagine Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Shavendra de Silva apologising to those massacred by our forces, and calling for medals being taken back from our murderous soldiers! That is reconciliation!

Instead, soldiers accused of war crimes here receive ambassadorships and high government office. What a horrid example! Indeed, our Government is vainly expending effort trying to stop through judicial orders the relatives of the dead remembering them in religious ceremonies, even when the courts rule that they have no authority to do that. Every opportunity at reconciliation is being frittered away.

Fearing the law

For truly innocent people, there is nothing to fear from the full application of the law. If our accused troops massacred no one, they should be the first to ask for a war crimes trial to clear their name. All will concede that – like President Donald Trump having a right to say, despite the evidence, that the 2020 election was rigged, and being entitled to his day in court – our accused soldiers, too, have the right to say that they killed no one and be allowed their day in court.

The resistance to that normal process shows that they have something to hide.

We Sri Lankans are conditioned not to trust the law. Every experience points to the law being politically biased. People charged and convicted under one government are mysteriously exonerated on appeal under another government. Others convicted under one government are pardoned under the next. Most in private admit not trusting our legal system.

The Election Commission and the law

There is really no law to speak of in Sri Lanka. I have documented many instances where the police and the Attorney General have blocked several election complaints from moving forward. We use laws as a tool, deciding to prosecute or not based on influence and political colour.

A good example is a complaint from the last General Election by the EPDP against Jaffna’s SLFP Leader Angajan Ramanathan, about propaganda meetings at temples and using road development projects, projected as due to personal effort.

As usual the Commission took its time and the complaints seem to have vanished. Then the EPDP wrote again, alleging that the Commission had done nothing, and threatening to take action against the Commission for covering up.

The matter came up as a Commission Paper at a recent meeting. It said that the matter had been passed on to the Police, and the Police had responded that they had investigated, and the reported incidents had not occurred. This contradicted independent press reports. We decided to ask the Police to check again carefully.

Upon hearing this, EPDP personnel had inquired from the DIG concerned. He allegedly responded that the complaint never came to them and that they never issued a report.

I asked the Commission Secretary for the Police report. He responded that he does not have a copy but the Commission Paper came from the Legal Division.

If confirmed, very serious questions will be raised over how a Commission can be run when internal documents cannot be trusted. The new Commission, when it takes office, would do well to investigate this if election laws are to have any meaning beyond showing the world that there are laws that are in force rather than laws for show. My experience is that it’s the latter.

With real laws, our soldiers have nothing to fear. Sri Lanka needs to look outside for standards or we will end up as a failed state the way we are heading. The Australian example is a good way to start.