Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday Feb 23, 2026

Monday, 10 July 2023 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Authorities can successfully implement the adjustment program only if they can command the cooperation of the people

A contentious issue pertaining to superannuation funds that include the giant in the sector, Employees Provident Fund or EPF, is the tax treatment of their gross earnings. These funds are subject to a tax of 14% on their gross income minus the cost that they have incurred in producing that income. In fact, the superannuation funds had not been subject to tax till 1989. In that year, the Government which had been faced with a severe revenue shortage due to the JVP insurrection in the South and LTTE war in the North had chosen to tax the working population’s meagre savings by imposing a tax of 10% on their gross income.

A contentious issue pertaining to superannuation funds that include the giant in the sector, Employees Provident Fund or EPF, is the tax treatment of their gross earnings. These funds are subject to a tax of 14% on their gross income minus the cost that they have incurred in producing that income. In fact, the superannuation funds had not been subject to tax till 1989. In that year, the Government which had been faced with a severe revenue shortage due to the JVP insurrection in the South and LTTE war in the North had chosen to tax the working population’s meagre savings by imposing a tax of 10% on their gross income.

As a result, EPF which is the largest fund became the largest single corporate income taxpayer in the country. It was therefore a cash cow for the Treasury. Hence, despite the representations made by many, including this writer as its Superintendent at the Central Bank, all the successive governments continued with the happy taxing of this lucrative source. Instead of abolishing this offensive tax, in 2017, the Yahapalana Government led by the current President Ranil Wickremesinghe chose to increase the tax rate from 10% to 14% to fill the empty coffers of the Government. As at today, it is this rate that is applicable to all these superannuation funds in the country.

Tax is on Gross Income and not on Net Income

The tax on superannuation funds at 14% has not been openly disclosed in the Inland Revenue Act of 2017. It has been done rather in a roundabout way. In the interpretation section of the Act (S 195) which is the most unusual place to announce a new tax, companies have been defined to include a host of societies catering to their members, namely, friendly societies, building societies, pension funds, provident funds, retirement funds, superannuation funds or funds or societies that have similar features. The common similar feature is that they should be owned and operated by their members. Then, in the first schedule to the Act that outlines the tax rates applicable to different individuals, it has been specified that these funds should pay a tax of 14% on their taxable income.

Taxable income has been defined in the Act (S 3) as the Assessable income minus qualifying payments. Since superannuation funds do not enjoy deductions on account of qualifying payments, their taxable income is identical with the assessable income. The only deduction which these funds can make when calculating the tax liability is the cost incurred by them in the production of earnings (S 11(1)). In a normal business, these costs include the salary bill, other administrative expenditures, depreciation of fixed assets, and loan losses that they have incurred in the production of the income involved.

In terms of the Inland Revenue Act, the capital expenditure items or dividends declared are not permitted to be deducted. The capital expenditure is not a current expenditure and hence only its depreciation part, according to the rates fixed by the Inland Revenue, is permitted to be deducted. Dividends are not an expenditure incurred in earning the income but something that arises after ascertaining the net profits and involve the distribution of such profits among the owners.

In terms of the Inland Revenue Act, the capital expenditure items or dividends declared are not permitted to be deducted. The capital expenditure is not a current expenditure and hence only its depreciation part, according to the rates fixed by the Inland Revenue, is permitted to be deducted. Dividends are not an expenditure incurred in earning the income but something that arises after ascertaining the net profits and involve the distribution of such profits among the owners.

Tax treatment of superannuation funds is different from that of financial institutions

The tax treatment of a superannuation fund differs from that of a financial institution with respect to the treatment of the interest paid to their fund suppliers. In the case of a financial institution, interest paid is a cost and therefore the institution can charge it to the profit and loss account in ascertaining the net surplus or deficit for tax purposes. The depositors and bondholders of a financial institution are not owners and hence, any payment to them is not a distribution of profits among them. However, a superannuation fund is owned by its members who are also beneficial partners. Hence, any payment to them, though it is called interest paid, for tax purposes, it is simply a profit distribution like the payment of dividends.

Since dividends are not allowed to be deducted when ascertaining the net surplus or deficit for tax purposes, the superannuation funds are also not allowed to deduct the interest paid when ascertaining the taxable income. As a result, financial institutions pay a tax of 30% on their net income, whereas superannuation funds pay 14% on their gross income. There, the two different rates are not comparable since the tax base involved differs significantly from each other.

An excessive punishment meted out to superannuation funds

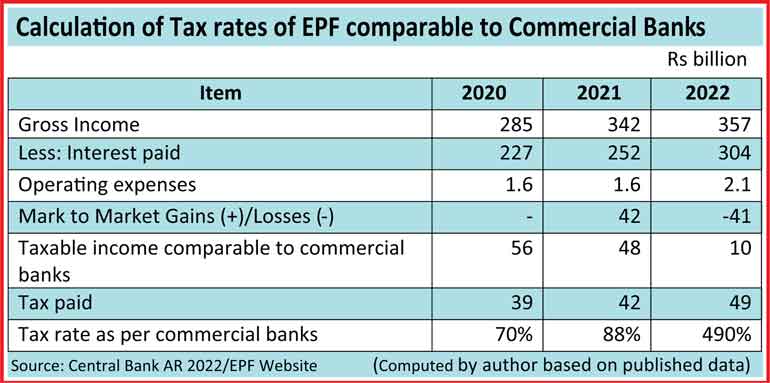

There have been recent attempts at treating these two rates as comparable when fixing the penalty tax rate of 30% on superannuation funds that fail to exchange at least 50% of their Treasury bond portfolio with Treasury under the ongoing domestic debt optimisation program. These are two incomparable numbers. When the taxes paid by superannuation funds, though at 14%, are expressed as a percent of the taxable income of financial institutions, the tax rate rises significantly. Table 1 presents my calculation of same for EPF for the years from 2020 to 2022. For this purpose, by using the published date, EPF’s income and expenditure accounts were represented.

According to the calculations, in 2020, the taxes paid by EPF, when expressed as a percent of its net income, the tax rate amounted to 70%, in 2021 to 88% and in 2022 to 490%. This is a severe tax burden on EPF members. Similarly, if the tax rate is increased to 30%, the tax rate based on the comparable tax base applicable to financial institutions will shoot to 149% in 2020, 188% in 2021, and 1050% in 2022. This will, therefore, be excessive punishment meted out to non-cooperating superannuation funds.

According to the calculations, in 2020, the taxes paid by EPF, when expressed as a percent of its net income, the tax rate amounted to 70%, in 2021 to 88% and in 2022 to 490%. This is a severe tax burden on EPF members. Similarly, if the tax rate is increased to 30%, the tax rate based on the comparable tax base applicable to financial institutions will shoot to 149% in 2020, 188% in 2021, and 1050% in 2022. This will, therefore, be excessive punishment meted out to non-cooperating superannuation funds.

Potentially negative net worth Central Bank should consult its staff before implementing DDO plan

Any debt restructuring against the creditor is painful. When a nation does so, it involves passing the pain on to all the creditors concerned. However, in the present DDO plan, it has been suggested to pass the burden on to the Central Bank in the case of Treasury bills and to superannuation funds in the case of Treasury bonds. The Central Bank will agree to exchange its Treasury bill portfolio amounting to Rs. 2.7 trillion and provisional advances that take the form of an overdraft extended to the Government amounting to Rs. 340 billion for a longer maturity bond repayable within 5 and 15 years. When the fair value of these bonds is reassessed comparative to the existing portfolio, Central Bank’s financial position may turn out to be a negative net worth.

Though a central bank can continue with a negative net worth for some time, it will badly reflect on its creditworthiness. This will adversely affect the Central Bank’s ability to raise short term funds for financing temporary liquidity shortages from external sources and providing guarantees to the Government when it raises external loans. Hence, it is a malaise which need be addressed immediately. But it will require the Government to recapitalise the Central Bank which in turn will be borne by the taxpayers of the country. Taxpayers will have to provide capital funds to the Central Bank either by paying more taxes or sacrificing some of their current benefits or both. Whatever the course of action taken, it will be a pain imposed on taxpayers. Further, since the negative net worth of a central bank will adversely affect the career prospects and emoluments of its staff, it is advisable to consult the trade unions in the central bank before implementing this proposal.

Pain inflicted on superannuation funds

In the case of Treasury bonds, members of superannuation funds will have to bear a pain. The authorities have excluded all other bond holders from the pain on the ground that some of those bond holders are already supporting Sri Lanka’s economic recovery program by paying higher taxes than that paid by superannuation funds. For instance, commercial banks pay an income tax of 30% and another tax of 18% on their value-added financial services. As mentioned above, this rough comparison is erroneous because it is two tax bases which are being compared.

In the case of Treasury bonds, members of superannuation funds will have to bear a pain. The authorities have excluded all other bond holders from the pain on the ground that some of those bond holders are already supporting Sri Lanka’s economic recovery program by paying higher taxes than that paid by superannuation funds. For instance, commercial banks pay an income tax of 30% and another tax of 18% on their value-added financial services. As mentioned above, this rough comparison is erroneous because it is two tax bases which are being compared.

The tax base of commercial banks is net income after deducting the interest paid, while that of superannuation funds is gross income where interest paid to members is treated as a profit distribution and hence non-deductible. As a result of agreeing to the DDO plan, they must be content with a lower future income flow. If they do not agree, they will have to pay a higher tax at 30% calculated on their gross income and not on the net income.

Whatever the course they choose, it is an inequitable pain-bearing. The threat that if they do not agree to DDO plan, the Government will have to default debt servicing is not an equitable distribution of the pain. That pain should be borne by all the Treasury bond holders since all of them have benefited in the past equally from the secured investment that guaranteed a fixed return.

Multiple tax stages applicable to EPF members

An important fact that has not been reckoned when deciding to pass the full pain on members of superannuation funds, especially those of EPF, has been the multiple stages at which they pay taxes to the Government. In the first instance, they pay a tax of 14% on their gross income and forego a sizeable portion of the would-be income they should have received. Secondly, when they make the contribution to EPF, such contributions are not allowed as a qualifying payment. Hence, they pay normal taxes on the money they saved as well. Third, when they get benefits from the fund, they are subject to a terminal benefit taxation as well if the total benefit is more than Rs. 10 million.

Fourth, since the Government does not adjust the interest rates on the securities it issues to fully compensate the prevailing inflation levels, the difference between the low rate which the fund receives and the rate comparable with inflation is a tax they pay to the government. In the name of equity and fairness, these multiple stage taxes should be reduced to a single stage. It will require the government to abolish the tax on gross interest earnings and subject them only to a terminal benefit taxation at the appropriate rates.

Inflation haircut by superannuation funds

The inflation factor on the holdings of Government securities has not been properly reckoned. When a consumer price index has advanced to a higher level, it is a price level that prevails as at a particular date. Though the inflation rate may be receding compared to the level of the index on a previous date, the current levels of prices remain taxing all the consumers. The holding of Government securities is a stock figure in money or nominal terms. To convert it to a real value, one should divide it by the prevailing value of the consumer price index and multiply by 100. For instance, in January 2021 in which month the new re-based Colombo Consumers’ Price Index or CCPI was released, the value of the index was 100. The same index has now advanced to 192 as at end-June 2023. It depicts a real value of 52 on every 100-rupee bond held by investors.

In other words, the value has fallen by 48% over this period. Consequently, the Rs. 3.4 trillion portfolio of EPF in nominal terms as at the end of 2022 has a real value of only Rs. 1.8 trillion. This is despite the growth of the fund at the prevailing interest rates through investing in Government securities. This reduction in the principal value can be termed an ‘inflation haircut’. Non-reckoning this part when offering the DDO plan to superannuation funds seems to be an oversight.

DDO haircut

Similarly, when superannuation funds agree to the DDO plan, they should necessarily forego a part of the interest income which they would have earned under normal circumstances. In the case of EPF, according to the Central Bank Governor Nandalal Weerasinghe, DDO will reduce the current EPF rate of return of 11.5% to about 9.4%. Therefore, this is simply a DDO haircut.

Similarly, when superannuation funds agree to the DDO plan, they should necessarily forego a part of the interest income which they would have earned under normal circumstances. In the case of EPF, according to the Central Bank Governor Nandalal Weerasinghe, DDO will reduce the current EPF rate of return of 11.5% to about 9.4%. Therefore, this is simply a DDO haircut.

Should the pain be passed on to all the bondholders?

If the pain is passed on to all the bondholders equally, it would have been a fair and equitable treatment. Though there is a fear that it would lead to instability of the financial system, that could be avoided it the pain is transferred to all equally. Then the people would have felt that they have been treated fairly. Such a trust is a must when a country goes through a painful adjustment to come out of a serious economic crisis.

Authorities can successfully implement the adjustment program only if they can command the cooperation of the people.

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)