Saturday Mar 07, 2026

Saturday Mar 07, 2026

Thursday, 23 November 2023 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ruined Rajapaksa heritage

Following Ranasinghe Premadasa?

Still the front-runner

The Economic Right

The best speeches of the Budget 2024 debate were by Anura Dissanayake, Sajith Premadasa, Dullas Alahapperuma and Prof. Charitha Herath.

The best speeches of the Budget 2024 debate were by Anura Dissanayake, Sajith Premadasa, Dullas Alahapperuma and Prof. Charitha Herath.

Dullas did a Michael Fassbender (‘The Killer’) on Ranil’s Budget, nailing its main features as the exact opposite of its stated goals.

Dullas did a Michael Fassbender (‘The Killer’) on Ranil’s Budget, nailing its main features as the exact opposite of its stated goals.

Charitha argumentatively rolled-out the soundest conceptual framework for a viable alternative economic strategy.

Charitha argumentatively rolled-out the soundest conceptual framework for a viable alternative economic strategy.

Sajith ran a light-saber through the lunacy of Ranil’s strategy, raising the most crucial question of the debate: “how can you meet your revenue targets and cover your deficits while deliberately shrinking the economy?”

Sajith ran a light-saber through the lunacy of Ranil’s strategy, raising the most crucial question of the debate: “how can you meet your revenue targets and cover your deficits while deliberately shrinking the economy?”

AKD’s was a compellingly serious speech; a strong articulation of a realist-progressive perspective and program for recovery, modernisation and development. (https://youtu.be/7lkwNN-0E3Q?si=5jrX-s37KPOj-LYY)

AKD’s was a compellingly serious speech; a strong articulation of a realist-progressive perspective and program for recovery, modernisation and development. (https://youtu.be/7lkwNN-0E3Q?si=5jrX-s37KPOj-LYY)

The competition and cooperation between these perspectives/personalities can provide a better future from this time next year.

Cry for Argentina

The victory of the economic rightist presidential candidate in Argentina, a Trump-Bolsonaro clone who will certainly polarise and destabilise Argentina in the coming years and eventually generate a left-Peronist backlash and outcome, should not mislead Sri Lankan readers. He was running against the Peronist government and its centrist Finance Minister. If you run against a centre-left government as an Opposition candidate, you can do so from the populist Right and win because you represent the protest vote against the status quo.

You can’t do that if you are running against a right-wing neoliberal President and his economic model.

What would have worked in Sri Lanka as a protest vote against a Gotabaya or Sirimavo-NM administration, is the opposite of what works against a Ranil-led status quo.

Budget 2024, Election 2024

The SJB forgot that Budget 2024 is the eve or commencement of Election Year 2024. SJB economic ideologues seem to confuse an election with an Economics paper at the university, set by a right-wing economics professor. Obtaining sufficient marks at an Economics exam is one thing, obtaining sufficient votes to win a nationwide election is quite another.

At an election you have to appeal to and persuade a majority of voters that you/your candidate/your party is their best chance of relieving their distress and realising their aspirations in the shortest possible time. An election is a competition at which you have to persuade a majority that you/your side is better than the other side in the task of representing them and defending their interests.

In that respect, the SJB didn’t do anywhere as well as it might have in the Budget 2024 debate. It also racked up an impressive score of ‘own goals’, thereby greatly helping the JVP-NPP.

The JVP-NPP’s main argument in the electoral arena 2024 is quintessentially the same as the JVP-DJV’s main argument in the civil war 1989, namely that the Premadasa-led rival formation is part of the old, elitist UNP Establishment and a continuator of its anti-people, anti-national policies.

In 1988-’89 the JVP-DJV allegation was proved totally wrong by Premadasa’s policies, and it was thereby defeated in the civil war. In 2023, the Premadasa-led SJB is going out its way to prove the JVP-NPP allegation right and therefore the latter is way ahead in the polls with an electoral victory a feasible prospect.

True, for his part, Sajith Premadasa disowned Ranil and neoliberalism in his Budget speech. But that was a single speech, barely reported, and the disclaimer was token. In the last 3 minutes of his speech, Sajith demarcated it from Ranil’s policy paradigm. That should have been the first 3 minutes, not a postscript.

Dr. Harsha de Silva’s contribution was illustrative and revealing. He reminded President Wickremesinghe that as PM he had led a 3-person team which included Harsha to a Harvard seminar by Prof Ricardo Hausmann. The seminar had identified ‘obstacles to growth’ in the Lankan economy and the team had committed to their elimination. Harsha asked Ranil why, when he now has the chance as President, he doesn’t “bring together all those forces committed to removing obstacles to growth”. In sum, a coalition of the neoliberal economic Right.

Harsha intervened later in the debate to defend the large-scale recourse to private money markets by Dr. Indrajit Coomaraswamy as head of the Central Bank under PM Wickremesinghe, creating that most toxic ISB node of our foreign debt overhang.

There couldn’t be a clearer establishment of continuity between the incumbent’s policies and SJB economics. This is the exact opposite of what JR Jayewardene and Ranasinghe Premadasa did: establish discontinuity with the policies of their predecessors.

In the Budget debate in 1976, the last of the Sirimavo-Felix regime, the intellectually sharpest radical-left critique of the Budget from the Opposition benches came from SLFP rebel-turned-independent Ronnie de Mel. The next year, he was JR Jayewardene’s pick as Finance Minister, bypassing Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake. In late 1987, readying for his breakout Presidential bid next year, Prime Minister Premadasa authored the Preface to prominent leftist Janadasa Pieris’ translation of Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika which argued for a reformed, renovated socialism. Sajith should process these.

Given the ‘multidimensional vulnerability’ documented by the international reports that Sajith and Harsha referred to in their speeches, the SJB could surely do better than list ‘improvement of the ease of doing business’ as the first step its administration would take. Telling that to a citizenry buried under the rubble of poverty is like reassuring those trapped under the rubble in Gaza that a new, liberalised import policy would bring in new bulldozers which can dig them out.

Since Independence, no one was more dynamic an industrialiser than President Premadasa, but he was elected President by leaning into the 1988 campaign with Janasaviya, a pioneering poverty-alleviation program.

Harsha de Silva argued in the Budget debate that Premadasa was able to undertake such programs because of a high rate of savings. On the contrary, when his Housing program was blocked in Cabinet in 1980 on the grounds that it skewed the figures, Premadasa funded it by launching the Sevana Sarana Development Lottery. A decade later, in the midst of twin civil wars, Premadasa funded the Free-Midday Meals program for school children through an innovative move by Mayor Sirisena Cooray of bundling the collection of payments of municipal rates. Premadasa supplied Free School Uniforms by securing the textiles from China. If there was a will, there was a way.

Premadasa was no empiricist; no captive of statistics. He was a thinker who brought a different perspective to bear, changing the construct:

“Whatever development we may bring about should be to the benefit of the poor. Development in any sense should help people live...!”

“Whatever development we may bring about should be to the benefit of the poor. Development in any sense should help people live...!”

--President Premadasa, ‘Providing Assets to the Asset-less’, 13.2.’89

“What sort of Sri Lanka do we want to create? We must strive to build a fair society for all. This means a society in which everyone is provided with the tools and the opportunity for advancement. The tools the State must provide are security, education, social justice, access to opportunity.”

“What sort of Sri Lanka do we want to create? We must strive to build a fair society for all. This means a society in which everyone is provided with the tools and the opportunity for advancement. The tools the State must provide are security, education, social justice, access to opportunity.”

President Premadasa, Annual Conference of the Judicial Service Association, 3.11.’90

Minimal solutions for the many, rather than high standards for a few, will be our vision for the immediate future.”

Minimal solutions for the many, rather than high standards for a few, will be our vision for the immediate future.”

President Premadasa, ‘Learning, Unlearning and Relearning’, 9.12.’90

SJB economic ideologues who nostalgically uphold UNP economic policy regimes and lament their incomplete implementation are obtuse. In Sri Lanka, any economic model that veered too far from a mixed economy in one or the other direction, triggered chronic instability which derailed the economic model itself. The UNP economic model resulted in uprisings (Hartal ‘53), landslide defeats (1956, 1970, 2019-2020), and armed rebellions (1987-’89). The SLFP-Left model resulted in armed rebellion (1971), landslide defeats (1977), and popular uprisings (2022). Given the Sri Lankan ethos, a social democratic socioeconomic model is the only thing that works in terms of sociopolitical stability and therefore, sustainable economic progress.

Political paradox

There is a glaring paradox in Sri Lankan politics today. With the government and the incumbent enormously unpopular, the traditional see-saw effect should cause the main Opposition’s—the SJB’s--popularity to rise, but it too is sinking, while the leftist Anura Dissanayake’s and his JVP-NPP’s popularity is rising.

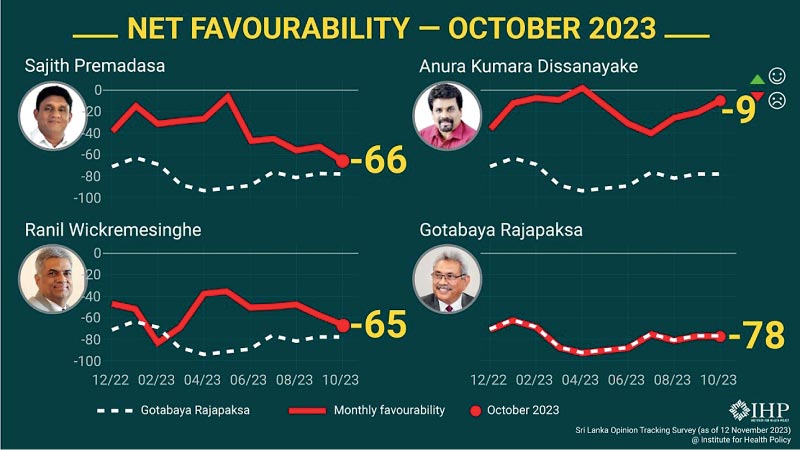

“In IHP SLOTS polling in October…NPP/JVP leader A.K. Dissanayake saw his ratings improve to -9 (up 10 points)…SJB leader, Sajith Premadasa’s favourability dropped to a new low of -66 (down 13 points) reaching similar levels to President Ranil Wickremasinghe whose favourability dropped 8 points to -65.”

“In IHP SLOTS polling in October…NPP/JVP leader A.K. Dissanayake saw his ratings improve to -9 (up 10 points)…SJB leader, Sajith Premadasa’s favourability dropped to a new low of -66 (down 13 points) reaching similar levels to President Ranil Wickremasinghe whose favourability dropped 8 points to -65.”

(https://ihp.lk/news/pres_doc/IHPPressRelease20231117.pdf)

The SJB, under the ideological-programmatic influence of its right-wing economic ideologues, has irrationally positioned itself at that end of the see-saw at which the unpopular President is sitting, not the opposite end which is rising. The SJB’s policy profile is barely distinguishable from that of the incumbent. It shares the same discursive-programmatic space as Wickremesinghe. It does not offer a change which is also an exit. That is a particularly painful paradox within a paradox: from lone Opposition MP through PM to President, Ranasinghe Premadasa always represented and manifested pro-people change, never the elitist establishment.

The SJB is protesting primarily against the Rajapaksas, who are not the rulers determining the economic policy which is grinding the citizenry, as is the President. Yet, the main Opposition’s targeting of Ranil is secondary and tangential. As Eran Wickramaratne clarified: “we aren’t saying President Ranil failed; we saying the Budget failed”.

The SJB’s problem is not with President Ranil Wickremesinghe and his economic policies but rather with the company he keeps, the Rajapaksa-led Pohottuwa. The voters cannot help but think that if the SLPP was dumped, the SJB would be happy to serve under Ranil with only a tactical tweaking of his economic agenda.

Anura Dissanayake and the JVP-NPP are ahead because the SJB has gifted them a monopoly of the protest vote against the status quo, the Establishment. Furthermore, the SJB’s comparative inactivity in the public domain, contrasts sharply with the NPP-JVP’s visible dynamism. It seems as if the main parliamentary Opposition may not be the main Opposition in the public eye, while the much smaller parliamentary Opposition, the JVP-NPP may be the main Opposition outside parliament in the public domain.

The space that the SJB occupied in the public imagination has been diminished because it was conceded and forfeited. Anura Kumara and the JVP-NPP have successfully, positively impacted the public imagination, though it hasn’t occupied as much of it as it thinks and as irreversibly as it thinks.

With the popularity of the incumbent and his administration going up in flames, according to both the Verite and IHP/SLOTS polls, why is the SJB climbing onto the pyre of Ranil’s popularity by hugging his economic ideology and policy agenda? It is being manipulated by those unscrupulously ambitious few who wish to sabotage a Sajith presidency 2024, seize the leadership of the SJB in defeat, and reunify it with Ranil’s UNP as a single right-wing party for parliamentary election 2025.

Vacant, vacated centre

As the results of the General Election of 1947 clearly revealed, at Independence in 1948 Ceylon was polarised between conservative Right and Marxist Left.

SWRD Bandaranaike’s exit from the UNP in 1951 and the SLFP’s founding created a durable moderate centre. After its ‘Silent Revolution’ in 1956 which shocked both Right and Left, they shifted to the centre so as to win.

With the collapse of the SLFP due its alliance with the Right (Ranil’s UNP), the centre was renewed with the birth of the SLPP. With the collapse of the UNP after its shift to the neoliberal Right (Ranil’s quarter-century), the centre was renewed with the birth of the SJB. Or so it seemed.

In reality, the SLPP abandoned the moderate-nationalist progressive populism of the Mahinda Sulanga (2015-2018) and shifted to the Right under Gotabaya Rajapaksa and now Ranil Wickremesinghe. It will suffer the SLFP’s electoral fate.

The SJB shifted right by an ideological embrace of the UNP’s most right-wing manifestations and moments, i.e., BR Shenoy proposals (1965), policies of the Ranil Wickremesinghe administrations (2001-4, 2015-2019) and global neoliberalism (Ricardo Hausmann), pivoting 180 degrees from President Premadasa’s pro-people, progressive policy paradigm.

Today the centre is vacant. There is a vacuum. We are almost back to 1947-48 and the sharp polarisation between Right and Left.

In 1956 the country would have swung Left to evict right-wing martinet Sir John Kotelawala, had SWRD’s SLFP not been available as a centre-left alternative.

The SJB sees itself as ‘the alternative Government’ but forgets the operative adjective ‘alternative’ and its difference from ‘substitute’ or ‘successor’. There cannot be a strong political centre with a right-wing economic ideology. The logical corollary of a strong political centre is a centrist economic ideology and model. Will Sajith and the SJB return home to his father’s progressive centrism?

Ranil-Gota are guilty

The Supreme Court verdict on the economic crisis is time-specific: 2019-2022. Mahinda Rajapaksa wasn’t President, Gotabaya was. Mahinda was rendered a powerless PM by Gota’s 20th amendment.

The verdict does not pertain to the two terms of the Mahinda Presidency. My wife and I were in the audience in Singapore in late-2009 when that country’s Deputy PM named postwar Sri Lanka as the fastest growing economy in Asia—itself the fastest growing region of the world-- outside of China.

The economy went into crisis in the decade it was run by Ranil Wickremesinghe as PM followed by Gotabaya as President.

The Central Bank bond scam; the removal of the Foreign Exchange Control framework dating from the early 1950s and its substitution by a permissive new law in 2017 which facilitated the massive outflow of dollars; and the hefty borrowings from the private money markets, were the Ranil-led UNP’s contribution to the crisis.

I was the first to warn against Gotabaya’s economic model in print, as early as May 2018, after he presented his policy manifesto at the Shangri-La Hotel:

“…My second concern is the economic policy model that was rolled-out at the Shangri-La by Gotabaya. As a high-growth strategy on the right flank of the Mahinda coalition, under Mahinda’s leadership i.e., a sub-set of a larger Mahinda policy paradigm, it would be fine. However, as a stand-alone model or the dominant (Presidential) one, it will generate major structural contradictions, triggering a cycle of conflict.

“…My second concern is the economic policy model that was rolled-out at the Shangri-La by Gotabaya. As a high-growth strategy on the right flank of the Mahinda coalition, under Mahinda’s leadership i.e., a sub-set of a larger Mahinda policy paradigm, it would be fine. However, as a stand-alone model or the dominant (Presidential) one, it will generate major structural contradictions, triggering a cycle of conflict.

The GR model as unveiled at Viyath Maga gave no importance to poverty, the peasantry, landlessness, inequity, poverty reduction, and social upliftment. It had no place for the people or social justice. The goal was high economic growth with law and order. Social questions and public welfare were conspicuously absent and the assumption seemed to be ‘trickle down’…

…The paradigm generates contradictions and resistance along three axial routes:

(i) The South-South axis, where social insensitivity, inequity and structural marginalisation will trigger clashes with students, workers, peasants, fisherfolk and neighbourhood communities.

(ii) The North-South axis, where tokenistic integrationism/assimilationism in place of a geopolitically sustainable political equation, will render the Tamil Question utterly intractable.

(iii) The Democracy-Autocracy axis, where the top-down technocratic model itself requires authoritarianism (Felix called it “a little bit of totalitarianism”) and will thereby erode legitimacy and trigger resistance…”

(https://www.dailymirror.lk/article/GOTABAYA-S-BREAKTHROUGH-150250.html)

Later, I challenged Gotabaya on his Shangri-La economic policy speech at a private dinner hosted by Dilith Jayaweera.