Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Saturday, 30 September 2017 00:54 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Similar to most developing nations in the east, Sri Lanka has had a long-standing tradition of disallowing abortions, even as far as drawing it to be a criminal offence punishable under the penal code of 1883.

Similar to most developing nations in the east, Sri Lanka has had a long-standing tradition of disallowing abortions, even as far as drawing it to be a criminal offence punishable under the penal code of 1883.

However, earlier this year, a cabinet select committee forwarded a proposal to the Government extending the exceptions for legal abortions to include, rape and incest, underage pregnancies and foetal impairment apart from the nominal case of potential harm to the mother.

Needless to say, these proceedings were inadvertently welcomed by feminist activists and the so called “neo-liberalists”. Yet it is my belief that the English were right in stating that the only reasonable argument for an abortion is the potential threat to a mother’s life, and I hope to validate this argument through the body of this opinion, by looking at abortion overall.

Current assertions

of the Penal Code

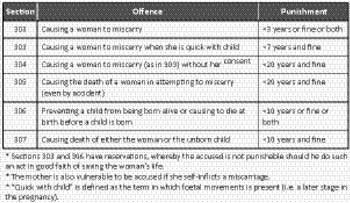

As stated in the introduction above, the penal code of 1883 reserves sections 303 up to 307 for the purposes of abortion as described in the table.

A theist’s dilemma

It is of no doubt that the first and foremost opposition for legal abortion is theocracy. Main stream religions including the Abrahamic trilogy vehemently call for the rights of the unborn child. Their common precept is that “life begins at conception and not at birth”. However, I’m of the opinion that this fundamental principle forwarded by theists is flawed.

For example, the Christian scripture in Jeremiah 1:5, Romans 8:29 and Ephesians 1:4 states that God has known us [the child] before the foundation of the world (even before we were formed in our mother’s womb). Therefore, it is quite adequate to state that life begins when God conceived us in his mind.

This causes further conflicts in religious interpretation of the principle of abortion and its applicability. This being, if life begins before conception, is the denial of human conception, abortion? If so, contraception could be a crime. So is the refrainment of intercourse. Should we penalise both the preceding, as done in the African continent following the pope’s call for not using contraception, ending up in a world where rising population could not sustain itself, depleting nature and its fertility.

Hence, even though theists have a noble ideology of the sanctity of life, I do not believe that religion answers the question of the beginning of human life satisfactorily.

The moral crisis

Founded on religion is a society’s moral code. Given the multicultural society that we live, our value system has been shaped by our history and the liberal precepts accepted by all. Thus, Sri Lanka together with many other nations, has signed onto the UN human rights treaty. Thereby, the state has the right to intervene in one’s family to protect the wellbeing of a child, provide an adequate environment for the child’s upbringing and protect the child’s right to be born.

Inherently, the state does have the obligation to protect a child even in a mother’s womb. Unfortunately, our moral values have also failed to provide us with an answer to the exact time a child is brought to life. So, when is human life first formed?

Medical ethics

Physicians have had the answer to this question long before we have. Is it accurate scientifically is for a later debate. Thus, medical ethics state that when a doctor treats a pregnant woman, he has two patients. This thereby implies that even though a doctor’s priority is the mother, his actions should capsulate the wellbeing of the child. So, does this answer our dilemma?

Sadly, it does not. This only validates our claim that life is ascertained even within the womb. Yet it fails to conceptualise the exact point in time where such life is brought into existence.

The pragmatist’s point

Having concluded that life is evident even within the womb, we move on further to analyse the exact point of life. The Oxford dictionary defines life as, “the condition that distinguishes animals and plants from inorganic matter, including the capacity for growth, reproduction, functional activity, and continual change preceding death”. The key words in this definition are ‘continual change’ and ‘functional activity’.

Functional activity could be the time in which animation of the human body is evident. Medical experts in this area would call it foetal movement while legalists simply term it, quick with child. And it is nothing but pure coincidence, that our penal code tends to provide increased sentencing for later stage abortions (sec 303). Does this mean that an abortion in the earlier trimester is valid? No. Our penal code still attributes it as a criminal offence. But in a strictly philosophical sense, are early stage abortions allowable?

No. As stated earlier, the second key phrase in the definition of life is ‘continual change’. From the initial formulation of an egg, a foetus changes continually to become a child in nine months. Hence it is undeniable in validating the religious fallacy that life begins at conception. Either that or we contact Oxford to change the definition for ‘life’. Moving on, now we will consider the ills of legalising abortion as a whole followed by the specific exceptions that are being proposed.

Promiscuity

Currently living in Australia, I have witnessed the social promiscuity to which abortion has curtailed a nation. ‘Sex’, as it seems, is a casual foreplay. Funny, yet functional, being a virgin creates an ‘awwww!!!!’ moment money can’t buy. Teenage fornication, adulterous adulthood and debaucherous single lives is surprisingly common. What has  this led to in the long run?

this led to in the long run?

Unfit parents and state dependent families. Ineffective contraception. Prop up of a ‘red light’ district and God knows what. In the UK, debates are currently hovering around second and third time abortion clients. A well-known parliamentarian identified it quite correctly as “abortion being used as contraception”. One might argue that we Sri Lankans do not share the same values of the English, as such legalising it here would not cause a social change.

Yet I beg to differ. Russian social conservatism is second to none, that it is the only non-Muslim country that punishes ‘gays’ with death. Just before the fall of the Soviet Union, where abortion was legal then, the number of abortions surpassed the number of registered births in a given year. Upon such revelations, Russia pulled back on its abortion rhetoric. I believe that this validates my claims of social promiscuity as a result of legalising abortions.

The social paradox

Unlawful abortions are rising in Sri Lanka. Reports state that as much as 54 abortions per 1,000 people is performed per annum in our country. As some of these treatments are done unprofessionally and not forgetting illegally, the risk it poses on the mother rises with it. So why is there an increase in abortions?

It is a mere fact that many women and young girls are being exploited by men both in the social pre-text and at their workplace. Independent women’s health associations have claimed that most work place related abortions stem up from the garment industry. Given the prevalent social conservatism, these women would resort to abortion in order to secure future marriage prospects and social disenfranchisement.

However, it is my belief that such acts of violence against these women can only be curtailed, if they come forward. I do know that it is easier said than done, but I seem to see no way around it. Sri Lanka does lack the communal benefits made available to women in such circumstances in developed nations, but it is our complacency that causes much pain. To cover up a crime, these women carry out a moral crime of denying the life a child formed through less favourable means. So, I ask, is it better to kill an innocent child than to punish the scoundrel who impregnated the mother?

Every mother, either by choice or not, should consider one thing. Our belief of social disapproval regarding pre-marital pregnancy, though true, is a fallacy. We have seen countless examples of children born through unbecoming circumstances, achieving great things. A child’s potential is not defined by its conception, but by its own ability. I hope that these arguments clearly articulate my disapproval of the first and second proposed exceptions to the existing code.

Who plays god?

The third proposed exception looks at providing the choice for abortions upon successful acknowledgement of a foetal impairment. This includes a poor quality of life upon birth and sometimes, the inability of a child to survive apart from the mother’s womb. So, who makes this judgment?

In the past, we have seen occasions where doctors have incorrectly diagnosed children with impairments before birth, while such assertions proved to be wrong upon arrival. I do not blame doctors for this, because countless experts have stated that diagnosing foetal impairments in itself is prejudicial and even if a foetus is impaired in some way, there is a chance that such anomalies could be cured within the womb or by medical intervention.

Yet, this proposed exception denies a child’s right to fight for its existence. Moreover, there is the question of medical validity. I am aware of the fact that the state has the obligation to provide a good quality of life for the unborn child, while potential foetal impairment could actually restrict it. But on the contrary, does the state have the right to deny a child its right to life due to its imperfections, while many barren women have literally expired all means to conceive? Fruit for thought!

(The writer is a FX trader and a poker enthusiast, www.jemuelcj.wordpress.com.)