Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Tuesday, 6 November 2018 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The plan was to slowly ease back into writing by focusing on the challenges posed by new technologies such as artificial intelligence and distributed ledgers. But my readers’ minds are on other things, like cross overs by Parliamentarians.

The plan was to slowly ease back into writing by focusing on the challenges posed by new technologies such as artificial intelligence and distributed ledgers. But my readers’ minds are on other things, like cross overs by Parliamentarians.

I was engaged with the Constitutional reform process in 2015 and 2016, especially on the 19th and 20th Amendments of 2015. The former was approved and is very much in the news. The latter, dealing with electoral reforms, was gazetted, not taken up for debate and died. The electoral-reform debate meandered on until it got mired in the swamp of delimitation.

Both the common candidate and the incumbent had promised to change the particular variant of Proportional Representation (PR) that had been in place since 1989. A few of us from civil society spent an inordinate amount of time discussing the pros and cons of various alternatives with representatives of political parties and nudging them toward consensus.

Factors conducive to corruption such as the high costs of campaigning across entire districts under the extant system were central to the discussion. The problems posed by coalition formation after elections and the related phenomenon of cross-overs were also debated.

How were cross-overs addressed in 2015?

Some who were involved in the drafting of the 19th Amendment are now talking about who was responsible for the exclusion of anti-cross-over provisions in that particular text. It was not outside the realm of possibilities to shoehorn such a provision into that ungainly and inelegant document, but it would seem that the logical place would have been in the 20th Amendment which dealt with how the Members of Parliament were to be elected and removed, etc. The still-born 20th Amendment of 2015 (Gazette Part II of June 12, 2015) included relevant provisions:

Section 99B(10): Where a vacancy arises in any polling division due to the resignation or expulsion of an elected member to represent any polling division or the termination of such member’s party membership or due to death or any other cause, the Commissioner of Elections shall take action to conduct a by-election for such polling division. Where a vacancy occurs in respect of a member elected under the proportional representation system, the secretary of such political party or the leader of the independent group has the authority to nominate a member for the particular polling division out of the candidates who contested the election or out of any additional candidates who have been given nominations but not contested from the polling division.

Provided that, in the case of an expulsion of a member of Parliament, his seat shall not become vacant if prior to the expiration of a period of one month from the date of such expulsion such member applies to the Supreme Court by petition in writing and the Supreme Court upon receipt of such application determines that such expulsion was invalid and, such petition shall be inquired into by three judges of the Supreme Court who shall make the determination within two months of the filing of such petition. Where the Supreme Court determines that the expulsion was valid the vacancy shall occur on the date of such determination:

The basic premise was that the ability of political parties to terminate the memberships of party members, and thereby expel those who crossed over, which is currently practically non-existent would be restored with safeguards for due process. The Amendment stipulated that a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court, and no other judicial body, could rule on the validity of the expulsion of an MP by a political party. The ruling had to be given within two months.

The above formulation is logical. An MP who won partly because of the party and partly on the strength of her personal popularity would have the chance of coming back even after a cross-over based on a new mandate from the voters of that particular polling division. One who entered Parliament solely on the strength of the party would not have such an opportunity.

Could this rule be applied rather than a blanket ban?

The above logic, if applied to the MPs elected under the current PR system, would result in those crossing over to another party for whatever reason being expelled by their parties, losing their seats, and being replaced by nominees of their party. The only safeguard would be judicial oversight of the expulsion process. None of the current MPs won solely on their own popularity. In order to vote for them, the voter had to first vote for the party that included them in the list. It is unjust for one elected as a result of being included in a party list to violate the discipline of that party and keep the benefits of being an MP, and perhaps the additional rewards proffered for crossing over.

It is easy, in the heat of the moment and in response to credible evidence of MPs being bought, to argue for a blanket ban. But it is not necessarily right. Absolute prohibitions of cross-overs convert MPs into slaves of their parties. Especially in countries like ours, where inner-party democracy is practically non-existent, such a ban would give enormous power to party leaders. The possibility, even if remote, of principled opposition to a party’s position would be eliminated. The results of prohibitions on cross-overs can be seen in the docile behaviour of MPs in Bangladesh, where party leaders are all powerful.

What can be done now?

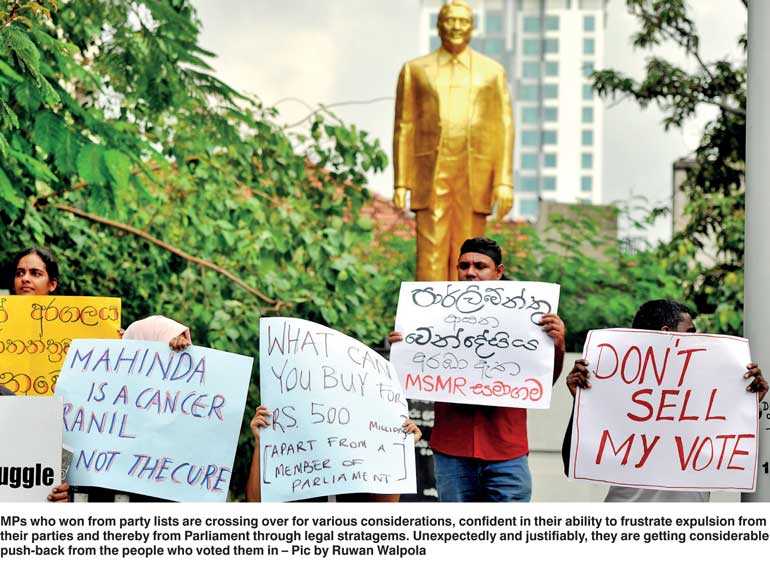

MPs who won from party lists are crossing over for various considerations, confident in their ability to frustrate expulsion from their parties and thereby from Parliament through legal stratagems. Unexpectedly and justifiably, they are getting considerable push-back from the people who voted them in. In the absence of a minimal change to the law, such as the limiting of judicial review by court and by time, this is the best that can be done at this time.

If it appears that the reform of the PR and preferential voting system will not happen, those seeking to reduce opportunities for corruption must campaign to strengthen the ability of political parties to maintain some degree of control over their members, subject to judicial oversight as envisaged in the 2015 proposal for electoral reform.