Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Wednesday, 11 September 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

“Interest rate” has become a buzzword in the day-to-day life of everyone irrespective of profession, social status or geographical location they are in. Be it a retired pensioner or corporate investor, interest rates has become a barometer for the social wellbeing.

At macro level, rate of interest is identified as the most crucial aspect of a market economy. It dictates the cost of borrowing and return on savings. The level of investment in the economy, consumer spending, inflation and economic activities prevails in an economy as a whole are influenced by the market interest rates. Hence, central bankers all over the world are concerned about market interest rates in exercising monetary policy of a country.

Monetary policy is the process by which a central bank manages money supply and the cost of money in their effort to achieve price stability and keep inflation within a targeted range. The reserve ratios or open market operations of a central bank can exert direct influence on the money supply of the economy, whereas policy rates of a central bank can be used as an indirect influencing factor.

In the Sri Lankan context Standing Deposit Facility Rate (SDFR) and Standing Lending Facility Rate (SLFR) can be used to influence the cost of credit. Monetary policy is generally been spoken from the perspective of borrowers and its argued that lower interest rates encourage borrowing in the economy resulting higher investment and ultimately economic growth.

The policy transmission problem

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has continuously pursued an accommodative monetary policy during the recent past. CBSL validated the market expectations in its fifth Monetary Policy Review with a downward adjustment to key interest rates by 50 basis points. The liquidity condition of the market was positively addressed by CBSL through the reduction of Statutory Reserve Ratio (SRR) by 2.50% in two instances, November 2018 and March 2019.

The measures by the CBSL are crucial in the present-day context to reignite economic activity, given the significantly weakened growth impulse of the economy. The Monetary Policy Review clearly reflects that CBSL is gravely concerned about the transmission of the impact of the rate cut into the economy.

It is clear that the Central Bank has been monitoring the lapses in policy transmission over the time. In April 2019, with the directions on Maximum Interest Rates on deposits, CBSL spoke about the need of speedy monetary policy transmission and reduction of bank lending rates. In the latest Policy Statement, CBSL decisively states that caps on market lending rate is an option on the table unless the intended reductions are not materialised by the banking sector.

Interest rate regimes: The Indian perspective

The concerns of CBSL are justifiable since the inefficient policy transmission restricts the scope of spurring credit growth. The decision of the Central Bank to use a heavy hand on banks to reduce market interest rates can be viewed as a speedy and effective alternative in the short term, given the restrictions on deposit interest rates already in place. However, it will not be a viable option for CBSL in longer term. There should be a proper mechanism in place to address the issue.

The lending rate regimes followed by Reserve Bank of India (RBI) provide a classic example for the evolution of a result-oriented mechanism. RBI has taken several approaches to develop a fair interest rate mechanism in the banking industry, since the 1960s. During the timespan of 1960s to 1990, RBI adopted administered interest rated regimes, prescribing minimum and maximum rate of interest to be charged on advances, interchangeably.

A major breakthrough to this mechanism came in 2003, with the introduction of Benchmark Prime Lending Rate (BPLR). It is the rate which banks charge for their most credit worthy borrowers. Even though BPLR was referred as a floor rate it was criticised as subsidising corporate customers at the expense of retail customers. The next era of policy measures, to synchronise bank interest rates with the market conditions, was introduced in 2010, with the introduction of the Base Rate Mechanism. The calculation of base rate includes all the elements of lending rates that are common to all type of borrowers.

There were four main elements of the calculation namely, cost of deposits, Negative Carry on Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) and Statutory Liquidity Ratio (SLR), Un-allocatable overhead cost and Average return on net worth (expected profit margin). Base rate acted as the minimum interest rate bank can charge from its customers. However due to variety of inefficiencies in base rate regime, RBI switched to a new system with a clear transparent calculation method and more responsive to monetary policy, with effect from 1 April 2016. It is call Marginal Cost of Funds based Lending Rate (MCLR).

What is MCLR??

Marginal Cost of Funds based Lending Rate (MCLR) is a comprehensive system designed to calculate the interest rates of a bank with a positive correlation to the RBI policy rate adjustments. It can be defined as tenor-linked internal benchmarks published monthly for different maturities. Actual lending rate will be arrived at adding components of spread to the MCLR. It is a minimum interest rate that can be charged to a floating rate loan. Spread will be added to this minimum rate base on business strategy and credit risk premium. A credit risk rating model should be used to calculate credit risk premium.

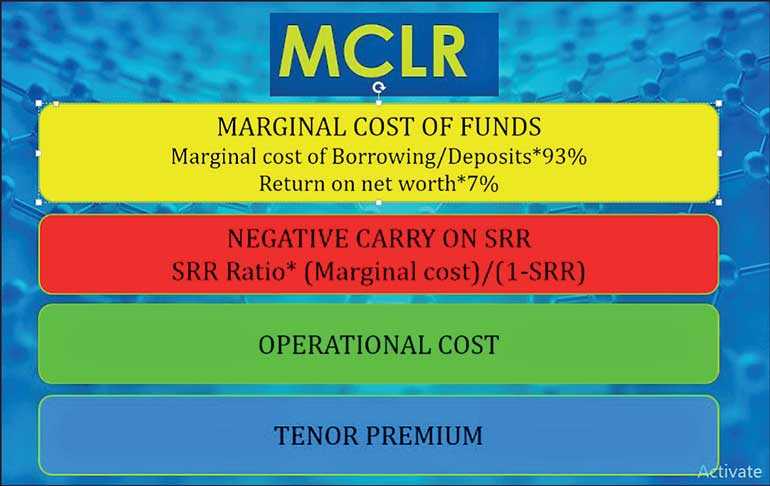

There are four elements of MCLR; Marginal Cost of Funds, Negative Carry on account of Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR) (in Sri Lankan context it is SRR – Statutory Reserve Ratio), Operating Cost and Tenor Premium.

MCLR in Sri Lankan context

MCLR is an effective mechanism which comes with transparency in methodology with a fair ground for both borrowers and banks. It enables banks to be competitive in the market while enhancing long-term value. The marginal cost of funds is the key component in focus in MCLR. It assesses the deposits as well as borrowings of a bank under different product categories as well as under different maturity baskets they are in. For example it is Fixed Deposits with three-month maturity and six-month maturity. Marginal cost will be the product of rates at which funds raised and balance outstanding (as of calculating date) as a percentage of total deposits and borrowings.

The other major component included under Marginal Cost of Funds is return on net worth. Net worth or equity considered under MCLR is the Tier 1 capital (7% of risk weighted assets) of banks. The cost of equity has being defined by RBI as the minimum desired rate of return on equity as a mark-up over risk free rate. The two components are given a weightage as 93% for marginal cost of borrowing and 7% for return on net worth.

The policy transmission to the wider market has been ensured under this component of MCLR. Specifically in the Sri Lankan context where deposit rates are also controlled MCLR will be an ideal solution to be explored. The calculation takes into account the latest interest rates and outstanding deposit/borrowing cost incurred by bank. Hence if bank changes deposit rates in response to a policy rate adjustment that new rate will also be applied in the cost calculation. Then the lending rates will automatically be adjusted in the market.

Negative Carry on CRR is a component which strikes a balance between bank’s interests and consumer’s interests. CRR (SRR in Sri Lanka) is the percentage amount, out of deposits liabilities, a bank has to maintain as cash balance (Vault cash) or deposits with central bank.

In the Sri Lankan context this is 5% of deposit liabilities). This portion of funds remain as idle assets of bank as physical money is not earning anything to bank and central banks are not paying any interest on bank deposits under them.

However on the other hand banks have incurred a cost for this portion of idle deposits. Hence under MCLR mechanism this cost will be taken into consideration in proportionate to the deployable deposits (1-CRR).

Operating cost segment refers to the cost associated with the loan granting process including the cost of raising funds. However banks are not allowed to include service charges (which banks recover from customers) to this segment as it will give an undue advantage to banks.

Tenor Premium is defined it as the costs arise from loan commitments of longer tenors. It refers to the premium chargeable for the liquidity risk component arises out of maturity mismatches. In simple terms for shorter periods tenor premium will be lower and longer period it will be higher.

MCLR, which is arrived as a combination of above components is not a static single rate, which defines minimum lending rate for banks. It is market sensitive set of rates which are reviewed monthly on a preannounced date. Banks shall publish this internal benchmark rate for minimum five tenors (overnight, one month, three months, six months, one year). This will be challenging to banks increasing operational and technological expenses. However the advantage is that MCLR will create a much competitive rate structure with lower rate for lower tenors.

External benchmarking

Although MCLR resolves the issue of policy transmission and responsive market interest rates, Reserve Bank of India has taken a step forward taking into consideration of aligning floating rate retail loans with an external bench mark.

MCLR together with all other prior mechanisms tested by RBI were internal benchmarks, which are calculated by banks themselves under the guidance of regulator. External benchmark may be a reference rate published by an independent benchmark administrator or present prevailing rate such as Repo rate or Treasury bill rates under different tenors. The benchmark rate should incorporate policy rate adjustments to transfer the adjustment to the market through banks.

However the central banks should be cautioned in nominating a specific benchmark. For instance, benchmark is T Bill rates and the rates are volatile over the year, which will affect the Net interest margins of the bank since the cost of funds will not change accordingly.

However, the next step beyond MCLR is not far from reach for the Sri Lankan market. A proper consultation with stakeholders and an independent body set up with the representations of industry veterans associated with the Sri Lanka Forex Association, Primary Dealers Association and Association of Professional Bankers may realise an effective external benchmark base system.

(The writer is a Banker and an Associate member of Institute of Bankers and could be reached via email at [email protected].)