Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 11 February 2020 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

It is that time of the year, when CEB goes to the Cabinet and the regulator (PUCSL) asking for emergency power – or its new euphemism “contingency power”, a term that does not exist in  the Electricity Act nor a defined procurement process.

the Electricity Act nor a defined procurement process.

Some diesel plants will appear, floating or otherwise. One paper quoted a senior CEB official speaking of a “drought” – confusing “drought” with “dry season”. The Government will be hard-pressed for energy with the threat of blackouts in the air. Despite bad reviews, this circus continues from 2016, making a lot of money for some.

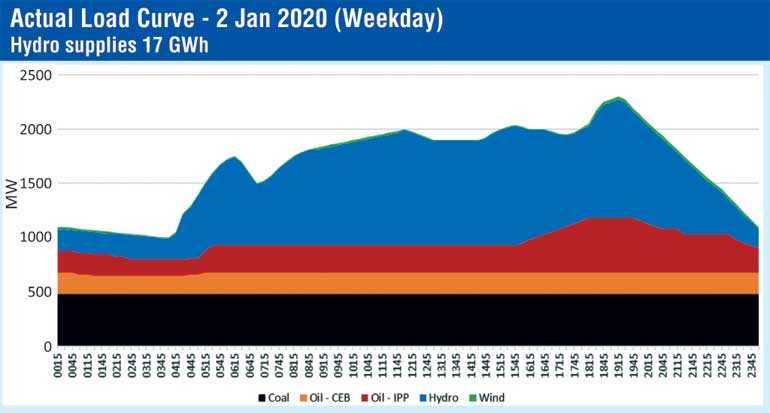

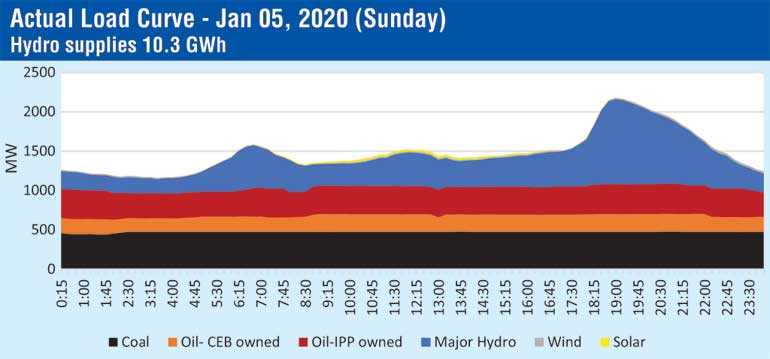

Sri Lanka currently does not have a problem meeting peak demand. The shortage is for energy during daytime. The majority of power cuts in 2019 and all of 2020 were during daytime. The peak demand is approx. 2,500 MW, the day peak being about 2,300 MW during a weekday. The country has approximately 3,300 MW of ‘dispatchable’ plants, quite sufficient to support the peak.

To supply the peak we need about 1,200 MW of hydro. In our current dispatch routine, we use a similar amount of hydro even during the daytime (especially on a weekday) rapidly depleting the hydro reserves. This leads to reservoir levels going down by about March-April, much earlier than the Yala rainfalls (south-western monsoon) creating an energy deficit.

Expanding solar PV would have reduced the amount of hydro used during daytime allowing us to retain water till May, as the simple analysis of load curves show.

The electricity generation capacity in Sri Lanka has not grown along with the increasing demand. This crisis was foretold as far back as 2016. A letter sent by the PUCSL to the Secretary of the Ministry of Power in April 2016, followed by a letter from the Secretary to the CEB in 2017, and then CEB Board Minutes directing the GM dated 29 June 2017 all stressed the urgency. The Board Minutes listed 995MW plants to be fast-tracked, but of this list, only 20MW of solar has been built by January 2020.

Even the blackouts of 2019 didn’t move things faster; only a few ground-mounted 1MW solar PV systems and 70MW of rooftop solar systems have been added since then. The CEB is yet to tender most of the plants in the Board Minutes from 2017, including oil-fired plants. Only emergency power is procured religiously.

The CEB still spent weeks in 2019 arguing for the solar rooftop tariff to be reduced, to slowdown the momentum of rooftop solar adoption. The uncertainty created by this move, along with multiple restrictions (circulars issued by the current CEB GM when he was the AGM of Distribution) has indeed slowed down the solar rooftop system deployment, increasing the deficit.

From 2016, CEB has refused to provide Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for small (less than 10MW) renewable energy projects citing an opinion of the Attorney-General, insisting these projects must be tendered. Of course, this opinion was not considered when the CEB provided three PPAs for Waste to Energy projects at Rs. 36 per unit. The end result was over 180MW of mini-hydro, 80MW of biomass and 1480MW of small solar PV (5MW or lower) stalling. The CEB has also refused/delayed the renewal of expired mini-hydro PPAs (approx. 70MW) for several years. These can come online as soon as the PPAs are signed, providing cheap electricity. However, CEB showed no hesitancy in renewing the PPAs of Ace Power plants outside the legal provisions of the Electricity Act, at a rate nominated by the company. Implementing the renewable projects by themselves would have saved us power cuts in 2019 and 2020.

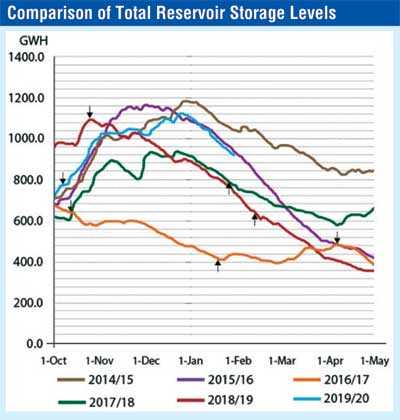

Sri Lanka received abundant rain during the Maha 2019 season with reservoirs reaching spill level. By 1 January 2020, CEB had 1100 GWh of hydro capacity – 200GWh more than it had at the same time last year. Only 1 January 2015 had higher reserves in the last nine years. 2019 also saw the addition of 70MW of ‘supplementary power’ from Ace Matara and Asia Power Horana on questionable legal grounds. Norochcholai Unit 1 repair completed on 4 February added another 80MW output – a 150MW plus against a 163MW deficit of Kelanitissa Combined Cycle Plant. Could the 200GWh surplus tide us through?

With the way things are going, probably not. But more renewables on grid and greater reliability of the Norochcholai coal plant would have been sufficient to overcome a deficit in 2020 and even the next few years.

Analysis suggests a link between coal power and emergency power/power cuts.

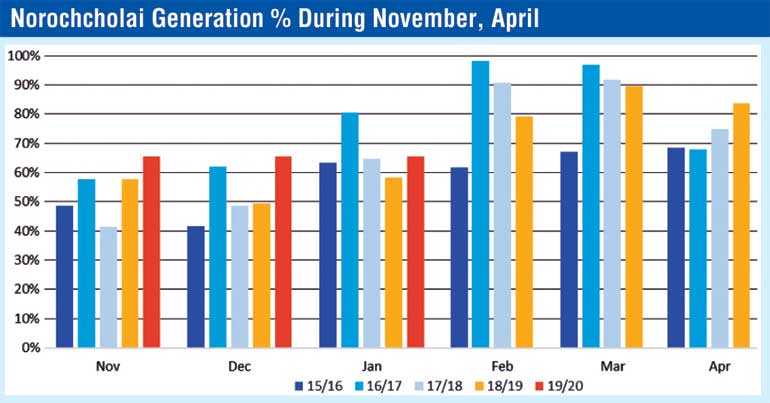

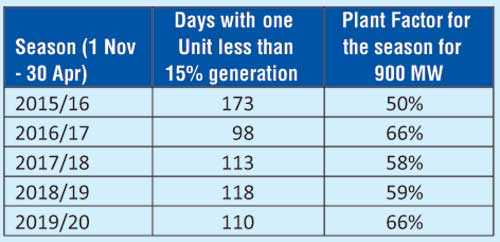

With the high variability of Maha rainfall (north-eastern monsoon) leading to a period of approx. five months of dry weather, it is important to use hydro reserves with care from November to April. One would imagine the CEB would use other plants such as coal at optimum level in this period. Analysis shows the coal plant running at significantly low plant factors and with high outages (planned or otherwise) during this period.

In 2015, Level A maintenance of Unit 1 planned for six months from July 2015 but took a whole year to power up; Unit 1 boiler tubes exploded in April 2017, though the plant was powered back up in May 2017 and ran 80MW afterwards till 2020. The shutdown of Unit 3 in December 2018 resulted in the plant not being able to be powered up for two months past the due date, leading to power cuts in 2019. The 90-day planned shutdown of Unit 1 in 2019 October only came back online on 4 February 2020 – 20 days later than scheduled. These 20 extra days depleted hydro reserves by approx. 120 GWh (10% of the reserves on 1 January). The storage level curves show the steep declines of 2016-17, 2018-19 and 2019-20 seasons.

Why the CEB schedules shutdowns during October-January when water has to be saved from mid-November is unclear, but it’s not difficult to see who benefitted. Why not schedule them during the Yala rainfall, using climate predictions to plan? The chart shows how the plant performed compared to system capability from November-April, leading to hydro depletion and heavy reliance on oil-based generation.

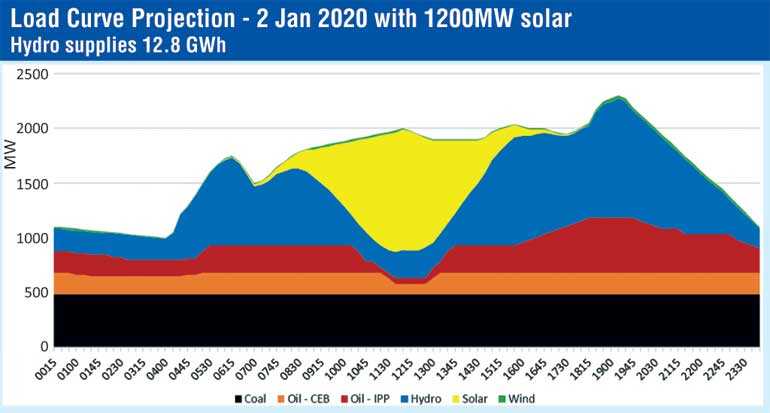

Solar PV generation would offset hydropower utilisation during the daytime, reducing the depletion rates, thus ensuring that we do not run out of water before the Yala rains arrive. CEB could have simply unblocked the pending proposals for ground-mounted solar, as well as rooftop solar at least after the power crisis in 2019. An opportunity gone unnoticed.

During daytime, it is possible to run the system with 200MW (the lowest discharge) and ramp up during evening and peak. The analysis shows that the difference between 2 January and 5 January hydro use was 6GWh. We could have had renewable energy easily saving this amount on a daily basis, be it solar, mini-hydro or biomass if enabled.

The analysis shows how a 1200MW solar PV in the grid would have not only displaced hydropower but also reduced some of the expensive oil-powered generation, saving CEB billions of rupees and reducing their loss. It is quite possible to build this capacity within 1.5 years through a combination of rooftop, ground-mounted and floating solar. A solar system can be built between four to six months from project approval.

"From 2016, CEB has refused to provide Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) for small (less than 10MW) renewable energy projects citing an opinion of the Attorney-General, insisting these projects must be tendered. Of course, this opinion was not considered when the CEB provided three PPAs for Waste to Energy projects at Rs. 36 per unit. The CEB has also refused/delayed the renewal of expired mini-hydro PPAs (approx. 70MW) for several years. These can come online as soon as the PPAs are signed, providing cheap electricity. However, CEB showed no hesitancy in renewing the PPAs of Ace Power plants outside the legal provisions of the Electricity Act, at a rate nominated by the company. Implementing the renewable projects by themselves would have saved us power cuts in 2019 and 2020

The analysis shows how a 1200MW solar PV in the grid would have not only displaced hydropower but also reduced some of the expensive oil-powered generation, saving CEB billions of rupees and reducing their loss. It is quite possible to build this capacity within 1.5 years through a combination of rooftop, ground-mounted and floating solar. A solar system can be built between four to six months from project approval"

But it is sad to see that, rather than doing so, CEB is keen to buy a further 200MW of oil-powered plants for one year. There is no conceivable way that new power plants will be able to remove gaps in the power system in one year – CEB’s track record for not building power plants on time speaks volumes. The only urgency CEB has displayed was for emergency power procurement; that haste is not seen in procuring any other form of power. They also remember the law only to hinder renewables, and forget it at other times, such as running Norochcholai power plant in violation of its EPL and national law. With this track record, one has to wonder why some people push for more coal power as a solution to the power crisis.

This of course is a first – I am yet to find a coal plant that was built to fix a short-term power shortage. The typical time frame used globally is seven years. The CEB claiming that the Norochcholai expansion can be done in three years is laughable at best. This project still has no completed feasibility study, without which an EIA cannot be made. A typical baseline for an EIA would require one year of data monitoring – even wind farms must have this. There is no funding agreement. In this day and age, there is no coal plant that goes forward without it being challenged in courts globally. Looking at the history of Norochcholai environmental violations, lax enforcement, church and community opposition, it is hard to see how this will be built quickly.

Not forgetting that building another coal plant will reduce the President’s 80% renewable energy target by 10%.

If the CEB is unable to build the coal plant by 2023 as they imagine (the likely scenario), we will again end up with emergency power.

The Sri Lankan power sector emergency power/supplementary power is dominated by a handful of companies – Aitkin Spence, Aggrekko, VPower and Altaaqa. The failure of the coal plant and the lack of renewables benefit these and other oil-based generation firms such as LTL. This excessive reliance on oil-based power (more expensive than renewables and gas) results in significant financial burden on CEB and the country.

Power procurement in Sri Lanka has always been a contested territory, never refusing to entertain analysts with claims and counter-claims that border on absurdity. The current emergency power purchase also at least raise numerous eyebrows.

According to the CEB generation plan 2018-2037, there are three oil-based power plants (100 MW, 70MW and 150MW) to be procured in 2018, three 35 MW gas turbines (2019 and 2020) and one 300 MW natural gas power plant to be procured in 2021 (in addition to the 300MW now stuck in courts). CEB has yet to tender these 625 MW and the large renewable energy plants scheduled. Somehow, they have ample time and resources to tender emergency power.

The advertisement for procurement of 200MW oil based ‘supplementary power’ for 12 months was published on 23 December 2019 with a return date of 16 January. Bidders had three weeks littered with holidays to bid. The procurement did not have regulatory approval – there is no provision in the Act to get ‘supplementary power’ – nor has there been an ‘emergency’ since what ails the grid is a systematic starving of generation capacity.

On 14 Jan, two days before the tender closure, the tender was extended till 30 January. It appears that the tender is awarded to a firm who also supplied emergency power last year. The timelines given in the tender is impossible to meet – for example, PPA signed in two weeks, and the project to be completed along with an EIA or IEE in four weeks. Even with CEB’s  super-efficiency for emergency power, this is a tall order. The Minister has stated they are thinking of extending the contract to three years; this possibly is not allowed in procurement guidelines.

super-efficiency for emergency power, this is a tall order. The Minister has stated they are thinking of extending the contract to three years; this possibly is not allowed in procurement guidelines.

The irony is that there is provision for CEB to procure 200MW for a longer term (three years), approved by the PUCSL, Ministry and the Board, all the way back in 2016/17. If this tender had been floated last year, at least after the power cuts, we would have gained a lower rate with good competition, and stopped us doing emergency tenders every year. Why the approved procurement was not done in time, but then rushed into an emergency purchase for a shorter timeframe is a good path of inquiry.

Sadly this is only one snapshot of what ails the sector. Unless serious reforms are done, there will not be any renewables in our grid, nor other types of power plants, and we will be continuously procuring emergency power year-on-year. The problems are deep-rooted; a culture that is fiercely anti-renewable, that can only worship emergency power.

We are left with nothing but to pray for rain.