Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 4 April 2018 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The prime objective of the National Economic Council established in 2017 was to mitigate national poverty while strengthening rural economy. The three-pronged economic development plan of the Council comprises infrastructure, economic development and construction projects.

The prime objective of the National Economic Council established in 2017 was to mitigate national poverty while strengthening rural economy. The three-pronged economic development plan of the Council comprises infrastructure, economic development and construction projects.

Vesting crucial powers upon the Council, the Government intends to gain plethora of benefits from such economic projects. In anticipation of economic (and other) gains the country initiates projects, but there are chances of those being a burden rather than a blessing. Initiation through decline phases, the economic projects display different behaviours.

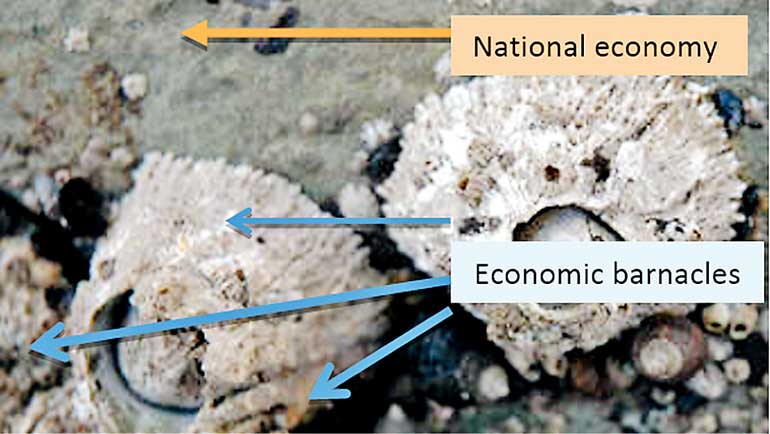

Some promising investments at origin deliver negative returns at decline, while certain projects at maturity do not retain its stability any further. Accordingly, it is wise to appreciate the imminent burdens rather than the visible promises. These economic burdens are named ‘barnacles’ as they adamantly ‘cling’ onto national economy and development.

Supported by capital budgeting and recurring costs, infrastructure projects are viewed as visible signs of development. The initial investment is high, reflects big figures and further has a significant running cost as well. Interestingly, the projects are short-life cycled and does not generate sufficient returns on investment. It creates an economic burden on the country as high maintenance costs impedes into the taxpayer’s finances when the projects mature into operational assets.

Economics that run on infrastructure includes road development projects (flyovers and highways), ports, harbours, airports, improved railways, and rural agriculture based on modern technologies. At initiation the projects seem promising, but towards stability phase only certain survive and others decline.

While perpetuity of projects are limited it begins to burden the economy with fuller force. The rising cost of living and incumbent expenses are hurdles to achieving full utilisation of projects. Could the general public afford to purchase a ticket in a full-fledged railway? This is the test of perpetuity for such assets.

The primary stakeholders, the general public, are influenced by both initiation and development of economic projects. The positioning of Sri Lanka in the Human Development Index (HDI) is thus rising steadily but slowly. Later on the Human Happiness Index and Human Innovation Index among others should also show a maintained rising. The Greater Colombo Economic Development Project (established under Principal Enactment No. 4/1978) presently known as Board of Investment projects since 1992 (under Amendment Act No. 49/1992) intends to strengthen economic development. For more than two decades, such BOI investments have shaped and sharpened diverse industries – hospitality, leisure and recreation, ethical commercial businesses and private-sector education.

Recording a positioning of 73 on HDI in 2016, Sri Lanka is showing high human development. A very high human development position is the level of self-actualisation in terms of economic gains. The multidimensional poverties of human safety (homicide rate), inequality, income (domestic food prices, domestic credit level, etc.) could be adjusted for long-term gains. After all, economic development is not driven by profits alone.

In volatile environments, the bargaining power of public for commodities need to be adjusted with changing economic situations. However, in debt-ridden times the question still triggers: Could we gain holistic returns on the economic projects and satisfy the needs of rural communities and the nation at large?

Barnacle 3: Construction – Lucrative or income regenerative assets?

The array of construction projects range from lifestyle living, commercial spaces to projects of wider national importance such as port and runaway expansions. Condominium projects benefiting individuals and businesses are a modern fashion for locals, expatriates and foreigners. This space management approach gives profits for real-estate owners and flow of income to the Government.

While a niche class benefits from this convenience living, the rights of shelter for low income earners are unaddressed. A question of affordability over accessibility, the economy is burdened and failed to quench the need of the wider society. The still remaining 80% provision for such projects could serve those hidden needs in a cost-effective manner.

In Asian nations there is a rising supply of condominiums, unmet by consumer demands as affordability inhibits purchasing powers (Forbes, 2017).The value-for-living concept rests on increased square feet and reasonable cost per square foot in a living unit. The inclusion of 15% VAT since March 2018 doubts the resale of assets at higher prices. Attractive projects may not have regenerative power on long-run.

Sri Lanka is an old-new country, small in geographic reach, but with an active regime of heterogeneous expansion projects. Thousands of years of heritage, over many decades of modern statehood have contributed to a project culture which has already created an identity of its own, while preserving the unique needs of different communities.

A socialist economy, Sri Lanka’s construction projects have absorbed many different social influences, as it blends expansion needs with optimising benefits, and strive to steer a course between Sri Lanka particularism and universalism. The constant search for sustainable projects is expressed through optimisation in a broad range of forms, to be appreciated and enjoyed by great many people as part of daily life. The interests of developing projects further do not generate profits, despite expansion at maturity phase. Widely known as “white elephants”, the country may have used economic feasibilities and environment impact assessment tools but, at much a surface level.

Infrastructure, economic development and construction projects the three dimensions of national economy depict societal and economic costs at different phases from origin through maturity to decline of projects.

After having enjoyed for many years one of the progressing GDP growth rates among regional economies, Sri Lanka is continuing the economic recovery it began in early 2010, after a thirty-year distinct slowdown in almost all economic activities. This trend continued in 2017, according to all economic parameters.

In the years 2011-2017 Sri Lanka’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) continued its slow but steady growth. In spite of the civil war, that caused temporary loss of the adjusted net savings, the GDP reached 11,048 per capita (PPP) in 2011. The speedy recovery and continuation of the rapid growth were again led by the business, financial and State sector projects, which expanded to 66.9% of GDP, resulting in domestic credit provided by financial sector (% of GDP) and gross national income per capita (2011 PPP$). Society is yet to decide – Is the national economy a casualty of the three-fold projects under the aegis of the Economic Council?

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law, researcher on legal-economic aspects and university lecturer.)