Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Wednesday, 4 September 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

We are in a period of waiting, the incumbent Government is moving towards closure, the pith and substance of the future government, unformed and unclear as yet. Some of the recognised political parties have already announced their candidate for the presidential race, although the process of negotiations and the gathering of alliances for the elections, is yet going on.

For sure, new political unions and fresh manifestos will be ceremoniously ushered, but in the personalities put forward, there will be a certain sameness. Unlike in the mature democracies, nearly all the candidates are old hands, or from one or two ‘political’ families. Vision, political skills and leadership is not given to all, it is a question of bloodline, or perhaps good ‘karma’. The system may fail repeatedly, the country in chaotic despair, but the old leadership mould will not be discarded.

Parliaments, exercise of the vote, political parties and ideologies are concepts of foreign origin. We did not aspire for them, but were adopted willy-nilly during the colonial era. Having no history in the development of these concepts, we see them through different eyes, using them in a different cultural context.

Elections anywhere in the world are public contests, often in the nature of a debating match between conflicting policies, with the voter as judge. To exercise judgment, we presume many things of the voter; maturity, a relevant value system and a reasonable awareness of the issues facing the country, being essential. However, his choice is limited by the system before him. The voter has to choose from one of the candidates put forward by a political party; the party may be democratic only in name, its processes centrally controlled, decision making in the grip of a select few.

In its design, the political system we have adopted is dialectical. There are conflicting opinions/ideologies and clash of “big’ personalities; electioneering generates excitement in otherwise drab villages; the local party organisers are motivated, purposeful, even violent; perhaps see the beginning of a political career for themselves.

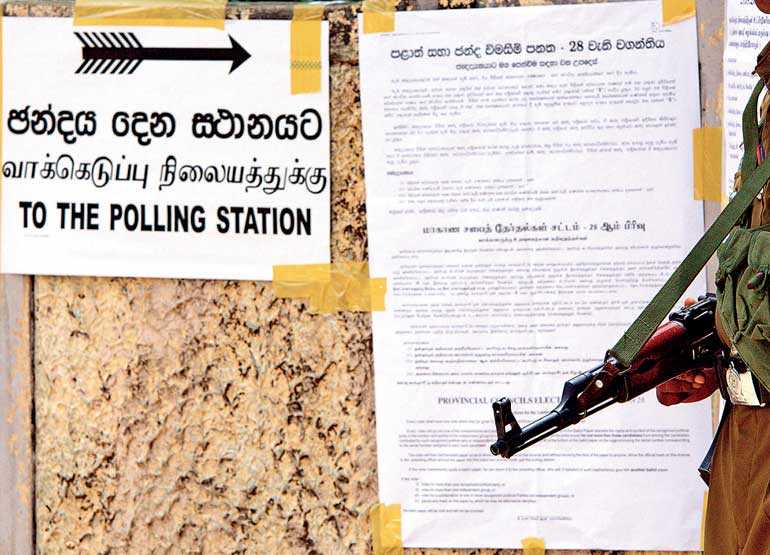

Matinee like personalities, ‘thuggish’ in appearance, the effect of pumping iron in their private gymnasiums showing, arrive. They are now dressed in white national costume, symbolic of a pure heart, immersed in the indigenous; travelling in long convoys of modern vehicles with a posse of bodyguards. Uniforms, guns, powerful vehicles; the irresistible military power of the State of Sri Lanka in display. And all this to impress the voter… on election day he trudges to the polling station.

This fundamental imperfection in the system goes to the heart of the matter. We expect a culture of democracy and integrity from politicians who emerge out of a not so democratic and terribly warped apparatus. For them, a political career is a livelihood, and an entry point to an elite status. As a result, there is a tendency to hog leadership positions as well as the jealous guarding of such positions until passed on to a person from his immediate family, in the manner of a family heirloom.

All our political woes, in all probability, arise out of this organised cheating of the franchise. There are elections, but only to choose between Twiddle Dee or Twiddle Dum (or their family members). Even when there is no direct family connection, political power is retained by a small oligarchy, more or less. The rest of the population, either incapable or invalidated, their only function, to periodically vote for whoever is put forward. There is an illusion of a democratic system, which only obscures the reality of a deep corruption.

In this country, we have so called political families, some who have dominated from pre-independence times. A fact which will only embarrass in a more mature society, is taken as an achievement to be boasted of here.

Increasingly, it is becoming apparent that mere systems, whether you call it a democracy or something else, cannot work to its potential unless the people are equal to it.

There are many defects in a democracy, but ultimately, it is the function of the voter to address them through their vote. When societies do not address fundamental issues weighing them down, or, are incapable of true reform, no system can deliver.

The Nobel Prize winning writer/philosopher V.S. Naipaul, who in his bestselling travel books was said to, “put nation States on the psychiatrist’s couch and then take a reading of their mental health”, has examined the endless distress of many a society.

In a long essay, ‘Argentina and the ghost of Eva Peron,’ Naipaul turned his searing eyes on that large country. Another time, another continent and another culture, true, but his observations of Argentina is not without relevance to us. I quote selectively:

“The dictator is overthrown and more than half the people rejoice. The dictator had filled the jails and emptied the treasury. Like many dictators, he hadn’t begun badly. He had wanted to make his country great. But he wasn’t himself a great man; and perhaps the country couldn’t be made great. Seventeen years pass. The country is still without great men; the treasury is still empty; and the people on the verge of despair.”

“Now after eight Presidents, six of them military men, Argentina is in a state of crisis no Argentine can fully explain. The mighty country, as big as India, and with a population of twenty-three million, rich in cattle and grain, Patagonian oil, and all the mineral wealth of the Andes, inexplicably drifts.”

“There are policemen with machine guns everywhere. And there are mounted police in slate grey; and blue-helmeted anti-guerrilla motorcycle brigade and those young men in in well-cut suits who appear suddenly, plainclothesmen, jumping out of unmarked cars. It is as if the energy of the State now goes into holding the State together. Law and order has become an end in itself: it is a part of the Argentine sterility and waste.”

“Argentina is a simple materialist society, a simple colonial society created in the most rapacious and decadent phase of imperialism. It has diminished and stultified the men whom it attracted by the promise of ease and to whom it offered no other ideals and no new idea of human association. New Zealand, equally colonial, also with a past of native dispossession, but founded at an earlier imperial period and on different principles, has had a different history.

It has made some contribution to the world; more gifted men and women have come from New Zealand’s population of three million than from the twenty-three millions of Argentines.”

“A businessman I met listed three new ways of thinking. Argentina no longer believed in a foreign enemy; no longer believed it was a European country: and it had lost the idea of the limitless wealth of the land.”