Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Saturday, 4 August 2018 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Much has been discussed about Sri Lanka’s tourism boom and the impending human resource shortfall that the industry will have to face.

Much has been discussed about Sri Lanka’s tourism boom and the impending human resource shortfall that the industry will have to face.

Recently a private sector initiative, organised by You Lead (of the USAID) unveiled a practical and comprehensive road map on how to address some of these issues. (You Lead: Sri-Lanka-Tourism and Hospitality Workforce Competitiveness Roadmap – 2018-2023)

Although detailed numbers and assessments are difficult to be derived accurately due to the lack of proper information, it is generally accepted that about 100,000 extra direct staff at various levels will be needed to service the expected growth in tourism in the next three years (Economy Next 2018).

The aforementioned road map details out for the first time, a private sector view of what needs to be done, with clear initiatives and action plans. It evaluates the impending shortfall in the next few years, assesses what are the training facilities available in the country, what are the shortfalls, and how to address these shortcomings. It also addresses the need to create a strong awareness among youth about the diverse career possibilities in the tourism industry for creative persons.

One aspect that has been touched upon in this road map is the large number of skilled Sri Lankans working abroad, and strategies to try and lure them back once their contracts are over. This led to considerable discussion about the exodus of well-trained hospitality staff to the Middle East and Maldives.

Hence it was felt that this would be an opportune moment to discuss this issue in greater detail in a monograph.

The Sri Lankan labour force

Local general employment: It is a well-known fact that the Sri Lanka has a high literacy rate of 95% (Ministry of Higher Education) with a labour force of 8,249,773 over the age of 18 years (Department of Census and Statistics 2016). The unemployment rate is about 4.5%.

“The number of women participating in Sri Lanka’s workforce has declined to 36% in 2016 from 41% in 2010” according to the World Bank. This is very much lower than the world average of 54% (World Bank: Labour force female participation rate 2016). In Asian nations this could be due to marriage, childrearing, and related household chores and gender discrimination.

Foreign employment: Remittances of Sri Lankans working abroad have assumed a great importance to the Sri Lankan economy. Today Worker remittances have become Sri Lanka’s largest foreign exchange earner and the country’s balance of payment has been highly dependent on the income generated by migrant employees.

Worker remittances in 2017 declined 1.1% to $ 7.16 billion from $ 7.24 billion recorded during the same period of 2016. (Ceylon Today 2018). The significance of remittances to Sri Lanka’s balance of payments and the economy, is of such a magnitude that some have described the contemporary Sri Lankan economy as a ‘remittance-dependent economy’.

Sri Lanka’s total foreign employed workforce has climbed to 1,189,359 (about 14% of the labour force above 18 years of age) by December 2016 according to Foreign Employment Minister Thalatha Athukorala.

There is an average ‘outflow’ per year of about 260,000 of which 66 % are males. House maids amount to about 26%. (Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment – SLBFE 2017)

Local tourism employment: Tourism is considered to be one of the foremost industries that provide a wide range of employment opportunities for young people. The Sri Lanka Development Authority (SLTDA) 2016 annual report indicated there are 146,115 staff in all grades in direct employment in the industry. However the tourism industry has a great multiplier effect, where it is estimated that every 100 direct jobs created in Sri Lankan tourism sector, generates about 140 indirect jobs in the supplementary sectors (WTTC, 2012).

Based on this Sri Lanka’s total tourism workforce should be around 205,000. However the real informal sector which includes the various trades men, beach operators, etc. who are involved with tourism, comprise a formidable number. Hence industry specialists are of the view that the real impact of tourism on the livelihoods of people could be more than 300,000.

According to the SLTDA some 15,346 new rooms will come into operation by 2020 in 189 new establishments in the formal sector. This author has estimated that the new staff required to service these new rooms will be about 87,000 only in the direct/formal sector). Taking into consideration the multiplier effect of the informal sector, this total could then swell to more than 200,000, resulting in a total estimated workforce in tourism of about 500,000 or more by 2020 (the WTTC expects this figure to be somewhat higher at 602,000 persons).

This would then mean that about 7%-8% of the Sri Lankan labour force would be engaged in tourism by 2020.

Local tourism employees in foreign employment: It is a well-known fact that a large number of Sri Lankan skilled hospitality employees are employed in the Middle East and Maldives. However there are no credible statistics of these numbers available.

Hence some conservative assumptions will be made as follows, to estimate these numbers:

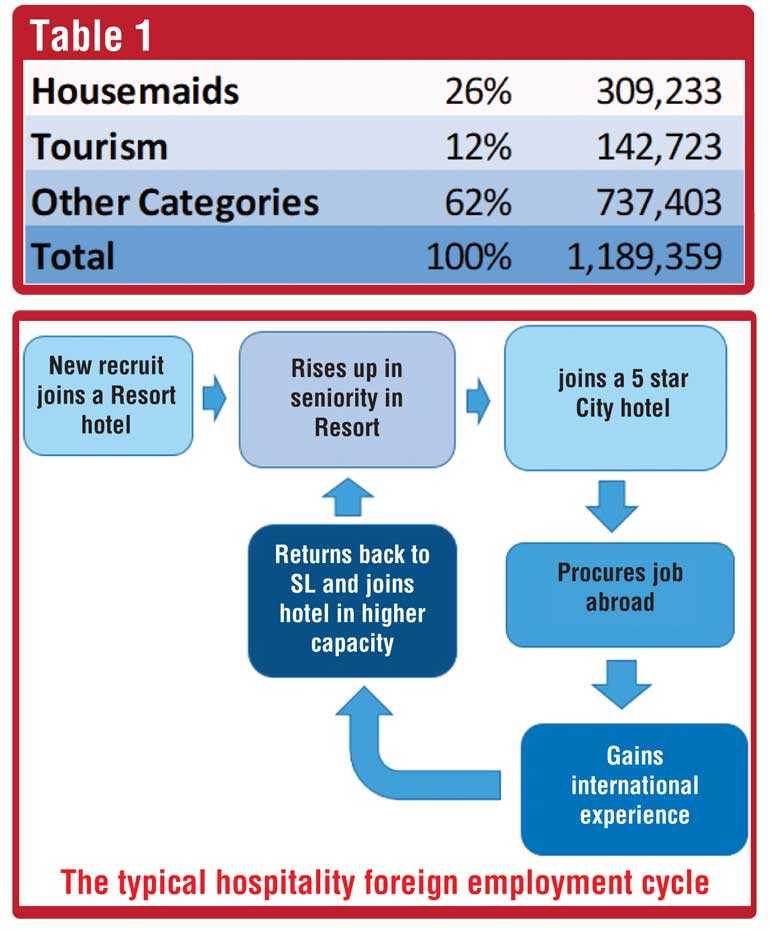

The total estimated SL workforce abroad: 1,189,359

Percentage of Housemaids (ref. SLFBE): 26%

Assume that 12% of the non-housemaid category are tourism related jobs

Hence on this basis the estimated breakdown will be as seen in

table 1.

This analysis indicates that some 140,000 SL tourism employees could be employed in foreign countries.

According to the SLFEB, on the average 260,000 employees leave for foreign employment each year.

If the same ratios as above is applied, then it would mean that the annual attrition or ‘outflow’ of tourism employees each year would be about 30,000.

The issue

From the forgoing basic analysis, it is seen that some 140,000 tourism employees are employed abroad and effectively ‘loses’ about 30,000 employees each year. The issue at hand therefore is whether this is a good thing or bad.

At first glance it appears that SL is losing its skilled tourism staff to establishments abroad, which is effectively a ‘brain drain’. However, closer study of this phenomena reveals a slightly different picture.

Step 1: As most tourism practitioners know in the hotel industry in SL, very often, raw untrained young people join a resort to start their working career in hospitality. They start from the bottom rungs, gain experience and work their way up the hierarchy in their chosen department or field. Even the basics of grooming and etiquette are instilled in the resort environment. Therefore most good resort hotels are really the basic training grounds for young aspiring hoteliers.

Step 2: After some years of gaining experience, the recruit rises up the ranks in the resort to higher positions of employment.

Step 3: Eventually the individual may leave the resort to work in a 5-star city hotel, to gain more experience and knowledge. Most often it is a young person’s dream to work in a star class city hotel, which gives him a wider exposure of the industry

Step 4: After some years of work in the 5-star city hotel, the young aspirant may look for employment abroad. Good pay, accommodation facilities, air tickets and other benefits lure these young men and women abroad on contractual employment. Most international hotels brands operating in the Middle East and Maldives look for staff having good experience in a 5-star environment. So it is not an unusual phenomena to see a steady exodus of trained personnel to foreign lands to work there.

Step 5: In a good foreign hospitality working environment, especially with international brands, there is a high level exposure to good practices and experience, most often working in close contact with world renowned experts in the respective fields. In this manner the young person gains a wealth of knowledge and experience while being well remunerated for his services.

Step 6: Most such foreign employment is on a fixed term contract, possibly renewable over a few cycles. Eventually the employee earns sufficient money for his living back home in Sri Lanka, and decides to come back. When he returns with his new experience and knowledge under his belt, most hotels in the city or resorts would very easily recruit him, at a much higher position than before he left.

Thus the cycle is closed, with the young employee now in a higher position both at work and society, with some reasonable savings in the bank to look after his family.

Conclusion

From the foregoing analysis and evaluation, it clear that in the case of the tourism industry, the exodus of employees going abroad, may not altogether be a bad thing for the industry. Staff who go abroad come back more skilled and experienced at the end of their contract abroad.

The author has many first hand experiences of seeing such employees returning back after enhancing their careers abroad. One worth mentioning is that of the Garden Maintenance Executive at one of the resorts the author was involved with. This particular employee was an agricultural graduate, and was soon promoted as a horticulturist to overlook the group’s environment assets. He procured a job as assistant horticulturist at the Ritz Carlton in Bahrain, where he eventually rose to being the head horticulturist of the group’s Middle East operations, winning several awards for the hotel group’s garden layouts. After serving for 12 years, he is now back, with an open job offer, to return to the Ritz Carlton group at any time.

There are many such inspirational and good stories of hospitality employee returnees. Hence it may not be all doom and gloom for the hotel industry due to employees leaving Sri Lanka for enjoyment abroad.

Quite apart from considering it a ‘brain drain’, perhaps the hospitality industry should consider this as a ‘brain gain’.

References: