Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Tuesday, 4 April 2023 00:40 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Despite terrorism being a worldwide phenomenon, the international community is yet to agree on a definition of terrorism. Ben Saul, Professor of International Law at the University of Sydney, who has written extensively on the subject, says: “The ordinary meaning of terrorism is simple: extreme fear.” While Sir Jeremy Greenstock, British Ambassador to the United Nations, said in a post-9/11 speech that ‘what looks, smells and kills like terrorism is terrorism’, Boaz Ganor, Director of the International Policy Institute for Counterterrorism emphasised: “An objective definition of terrorism is not only possible; it is also indispensable to any serious attempt to combat terrorism.”

Despite terrorism being a worldwide phenomenon, the international community is yet to agree on a definition of terrorism. Ben Saul, Professor of International Law at the University of Sydney, who has written extensively on the subject, says: “The ordinary meaning of terrorism is simple: extreme fear.” While Sir Jeremy Greenstock, British Ambassador to the United Nations, said in a post-9/11 speech that ‘what looks, smells and kills like terrorism is terrorism’, Boaz Ganor, Director of the International Policy Institute for Counterterrorism emphasised: “An objective definition of terrorism is not only possible; it is also indispensable to any serious attempt to combat terrorism.”

Need for a precise and clear definition

The UN Secretary-General, reporting to the General Assembly on the implementation of the UN Global Counterterrorism Strategy on 2 February 2023, warned against using vague and overly broad definitions of terrorism and related offences in domestic legislation as they would often result in heavy-handed implementation, leading to ineffective and counterproductive counterterrorism responses. He continued: “In some contexts, counterterrorism laws and measures continue to be routinely misused to label civil society actors, including human rights defenders, as terrorists and to prosecute them for terrorism-related offences with a view to obstructing their work. In other instances, counterterrorism measures are introduced to restrict civil society access to funding and increase reporting requirements beyond what may be reasonable. Reprisals against human rights defenders and the stigmatisation of civil society actors for their engagement with the United Nations are of particular concern, as they are frequently applied through the misuse of counterterrorism legislation. Women’s rights organisations and women human rights defenders are particularly affected by such practices.”

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) emphasises in its Handbook on Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism that while terrorism needs to be countered with all the means at the disposal of the State, counterterrorism measures that ignore or damage human rights are self-defeating and unacceptable in a society guided by the rule of law and democratic values (page 17). The handbook was finalised after extensive consultations with criminal justice and human rights experts from across the globe, including the writer.

According to the UNODC, in defining terrorist acts or terrorist-related crimes, States must observe the basic human rights principle of legality, which requires precision and clarity when drafting laws. This principle of general international law requires that the criminalised conduct be described in precise and unambiguous language that narrowly defines the punishable offence and distinguishes it from conduct that is either not punishable or is punishable by other penalties. Accordingly, the principle of legality also entails the principle of certainty, which means that the law must be reasonably predictable in its application and consequences (page 37).

Although the international community is yet to agree on a definition of terrorism, treaty-based terrorist crimes are found in universal counterterrorism instruments numbering nearly 20. They cover specific areas such as aircraft hijacking, aviation sabotage, violence at airports, the safety of maritime navigation, the safety of fixed platforms located on the continental shelf, crimes against internationally protected persons, the unlawful taking and possession of nuclear material, hostage-taking, terrorist bombings, funding of terrorism and use of an aircraft as a weapon. A comprehensive general treaty on terrorism has eluded the international community, mainly due to the absence of a universally agreed definition.

PTA, CTA and ATA

The Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act of 1979 was originally enacted to be in force for one year only. But in time, it became a permanent feature of our body of law. Today, there is wide agreement that the PTA should be repealed, although there is no agreement on what should replace it, some suggesting that a new law compatible with our international obligations be enacted, and others suggesting that a narrowly-worded offence should be included in the Penal Code.

The Yahapalanaya government introduced a Counter Terrorism Bill (CTA), which was not even taken up for debate as there was opposition to it from both sides. The present government has published a Bill for an Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), which, too, has run into opposition from political parties, trade unions, media persons and civil society organisations regarding the definition of offences and the procedures involved, including investigation, arrest and detention. The focus of this article is the definition of offences.

The Yahapalanaya government introduced a Counter Terrorism Bill (CTA), which was not even taken up for debate as there was opposition to it from both sides. The present government has published a Bill for an Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA), which, too, has run into opposition from political parties, trade unions, media persons and civil society organisations regarding the definition of offences and the procedures involved, including investigation, arrest and detention. The focus of this article is the definition of offences.

Proposed section 3 of the ATA provides the crucial definition of terrorism. A person who commits an act or illegal omission set out in subsection (2) with the intention of (a) intimidating the public or section of the public; (b) wrongfully or unlawfully compelling the Government of Sri Lanka or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; (c) unlawfully preventing any such government from functioning; (d) violating territorial integrity or infringement of the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country; or (e) propagating war or advocate national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence commits the offence of terrorism.

The acts set out in subsection (2) are: (a) murder; (b) grievous hurt; (c) hostage taking; (d) abduction or kidnapping; (e) causing serious damage to any place of public use, a State or governmental facility, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; (f) causing serious obstruction or damage to or interference with essential services or supplies or with any critical infrastructure or logistic facility associated with any essential service or supply; (g) committing the offence of robbery, extortion or theft, in respect of State or private property; (h) causing serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section thereof; (i) causing serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; (j) causing the destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; (k) causing serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic analog, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; (l) being a member of an unlawful assembly for the commission of any act or illegal omission set out in paragraphs (a) to (k); or (m) without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives, or any article or thing used or intended to be used in the manufacture of explosives, or combustible or corrosive substances or any biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapon, other nuclear explosive device, nuclear material or radioactive substance or radiation emitting device. Significantly, an ‘essential service’ is not defined.

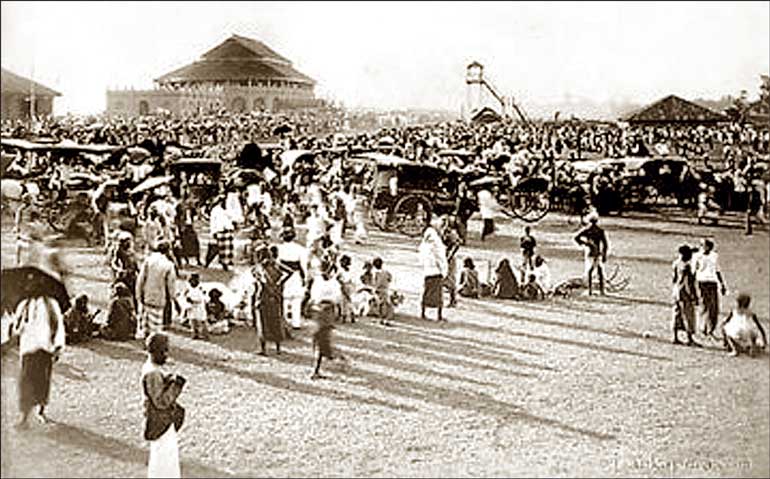

The offence of terrorism, as defined in the CTA, was not much different. Participating in a discussion on the CTA in the Parliamentary Oversight Committee on National Security, the writer pointed out that if the CTA had been law during the Hartal of 1953, the then Leader of the Opposition, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike and opposition leaders Dr. N.M. Perera, Dr. Colvin R. De Silva, and Philip Gunawardena would have all been convicted of terrorism for instigating the Hartal. Riots were widespread in certain parts of the country. Roads and rail tracks were blocked. In Randombe, Balapitiya, the Colombo-Galle road and the rail track were blocked by the protestors, with women baking hoppers on the road and the track! Communications were disrupted.

The Hartal brought the government to a standstill, and the Cabinet of Ministers had to meet on board the British ship HMS Newfoundland berthed in the Colombo harbour. There were some acts of sabotage and violence, and illegal acts were committed. Yet, they were not terrorist acts by any standard and were mostly ignored. The SLPP, TNA, JVP, and some members of the Yahapalanaya government opposed the CTA, and the Bill was not proceeded with.

Many acts committed during the Hartal would come under the ATA definition of terrorism. So would many acts committed at Galle Face, in the Presidential Secretariat and in the President’s House during the Aragalaya last year. Many such actions would amount to transgressions of existing laws but were not ‘terrorist’ acts. Perpetrators could be dealt with under such ordinary laws.

‘Bandhs’ and ‘Gheraos’ are common occurrences in India. A bandh, a form of civil disobedience, results in a shutdown, with shops closed and transport paralysed. While a Bharat bandh happens across the entire country, others would be limited to a city or a state. A gherao, meaning ‘encirclement’, is a protest where workers prevent managers and fellow workers from leaving a place of work or encircle and paralyse an institution until their demands are met. In 2018, the Bar Council of India threatened to gherao the Parliament to protest against the Higher Education Bill. Gheraos of State Assemblies are not uncommon. During the farmers’ protests of 2020-21 that went on for months, several government offices in New Delhi were gheraoed. Many laws are broken during bandhs and gheraos, but these actions are mostly tolerated in the greater interest of democracy. But never have we heard of people participating in bandhs and gheraos being dealt with under anti-terror laws.

Strikes and protests as terrorism

A significant feature of the proposed Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) is that offences are very broadly defined and thus bring within it conduct without a reasonable nexus to terrorism that could otherwise be dealt with under ordinary laws. This is precisely what criminal justice and human rights experts warn against.

A few examples would be helpful. The object of a strike is to prevent the provision of a service or the conduct of an activity—in short, to paralyse the institution concerned. Promoting strikes is one of the legitimate objects of a trade union recognised by the Trade Unions Ordinance. However, our courts have held that the right to strike can lawfully be curtailed. Let us take the case of a strike in the health sector that has been declared an essential service under the Public Security Ordinance and is thus illegal.

Under section 3(i)(b) of the AAT, engaging in the strike would amount to ‘wrongfully or unlawfully’ compelling the government to provide health services to the public. It would be an act prohibited by section 3(2)(h) for ‘causing serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section thereof’ and amounting to the offence of terrorism punishable under section 4(b) with rigorous imprisonment for a term that can extend to twenty years and a fine extending to one million Rupees and the possible addition of forfeiture of all movable and immovable property. Virtually any strike could be brought under the ATA due to the very broad definition of terrorism.

The same would apply to a protest that is not violent but results in the government being unable to provide a particular service. Let us take the example of processions taken out by lawyers throughout the country protesting the possible summoning of some judges of the superior courts for allegedly violating the privileges of Parliament by making a judicial order. The processions are massive, and the lawyers purposely block the roads to prevent buses from operating to make the public aware of the reason for their protest. Blocking roads is illegal under ordinary law. Under section 3(i)(b) of the AAT, it would amount to ‘wrongfully or unlawfully’ compelling the government to provide transport services to the public. It is an act prohibited by section 3(2)(f) being an ‘interference’ with an essential service, which is not defined by the AAT and is thus capable of broad interpretation. Lawyers participating in the protests would commit the offence of terrorism and be liable to be punished, as in the case of a strike.

One could give many examples of such actions which transgress ordinary law but are not, by any stretch of the imagination, terrorist acts. Such actions must either be dealt with under ordinary law or ignored in the broader interest of democracy.

Terrorism without terror

The writer submits that, in general, only acts that aim at creating ‘terror’ or a ‘state of intense or overwhelming fear’ should come under the definition of terrorism. There can be exceptions. It is not impossible that a person committed to the use of terror would commit a particular act in pursuance of such a goal without necessarily resorting to violence. For example, when a member of an extremist organisation sabotages an electronic or automated or computerised system, s/he commits an act of terrorism, although there is no violence. But the same act could be done by, say, a whiz kid without a similar intention, in which case s/he could be dealt with under normal law but not as an act of terrorism that entails a long period of pre-trial detention and severe punishment. Exceptional cases where no there is no terror but committed to further the objectives of a terrorist organisation need to be criminalised as distinct offences.

It is submitted that the general offence of terrorism should have, as an essential element, the creation of ‘terror’ or a ‘state of intense or overwhelming fear’. Specific cases where terror is not used but committed in pursuance of the object of an extremist organisation that uses terror should be dealt with separately. The definition of terrorism in Article 421 of the French Penal Code Acts is instructive in this regard. For acts to come under that Article, they must be ‘intentional, connected to either an individual or a collective enterprise, and intended to gravely disturb the public order by way of intimidation or terror’.

The European Union adopted a ‘Framework Decision on Terrorism’ in 2002, in which a terrorist act is defined narrowly as one which ‘may seriously damage a country or an international organisation where committed with the aim of seriously intimidating a population, or unduly compelling a Government or international organisation to perform or abstain from performing any act or seriously destabilising or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organisation’.

The EU definition enumerates nine types of specific terrorist acts: (a) attacks upon a person’s life which may cause death; (b) attacks upon the physical integrity of a person; (c) kidnapping or hostage-taking; (d) causing extensive destruction to a Government or public facility, a transport system, an infrastructure facility, including an information system, a fixed platform located on the continental shelf, a public place or private property likely to endanger human life or result in major economic loss; (e) seizure of aircraft, ships or other means of public or goods transport; (f) manufacture, possession, acquisition, transport, supply or use of weapons, explosives or of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons, as well as research into, and development of biological and chemical weapons; (g) release of dangerous substances, or causing fires, floods or explosions the effect of which is to endanger human life; (h) interfering with or disrupting the supply of water, power or any other fundamental natural resource the effect of which is to endanger human life; and (i) threatening to commit any of the acts listed in (a) to (h).’

The broad definition of terrorism in section 3 of the ATA has many other serious consequences. Under section 82, where the President has reasonable grounds to believe that any organisation is engaged in any act amounting to an offence under the ATA, he may proscribe such organisation. Being a member of a proscribed organisation is an offence that could be punished with imprisonment of up to ten years and a fine of up to one million rupees (sections 6 and 14).

Under section 10, any person who encourages the public to commit the offence of terrorism would be punished similarly. Any person who publishes a statement of such encouragement would also be punished. This includes a publication in the print media, internet and electronic media. Taking the example of the 1953 Hartal, its objective was to paralyse the government, which would have amounted to terrorism if the ATA had been in force. Opposition leaders who encouraged people to join the Hartal would then be ‘terrorists’. Similarly, trade union leaders who call a general strike, which would obviously paralyse essential services, would be punished as ‘terrorists’.

Although the focus of this article is the definition of offences under the ATA, the writer wishes to refer to another provision that could be used to stifle protests. Under section 85, the President may, on the recommendation of the IGP, the Commander of the Army, Navy or Air Force or the Director-General of the Coast Guard, stipulate any public place or other location to be a prohibited place. No guidelines whatsoever are laid down. Any person entering a prohibited place is liable to imprisonment not exceeding three years and a fine not exceeding three hundred thousand Rupees or both.

In conclusion, the ATA is replete with provisions that violate the fundamental rights of the People. As fundamental rights are one manner of exercising sovereignty, the Bill as a whole violates the sovereignty of the People. It, therefore, requires a two-thirds majority in Parliament and the approval of the People at a referendum.