Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Friday, 14 February 2020 00:05 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

There is a strong correlation between the complex crisis Sri Lanka is currently facing and the ancient history of Sri Lanka. The way Sri Lankans think today, is to a great extent, influenced by various  interpretations made on the history of the country rather than the objective interpretations of historical facts themselves.

interpretations made on the history of the country rather than the objective interpretations of historical facts themselves.

Taking this fact into consideration, I ventured to revisit the history of Sri Lanka with a critical and analytical aproach. My attempt eventually ended up in writing a book on the history of Sri Lanka titled ‘Sri Lanka: Culture of History’.

It can be considered a study covering a long period of history from the establishment of earliest settlements in Sri Lanka to the end of the British rule. It is not a book compiled with systematic sequence of events; rather it can be described as an attempt to understand the riddles of history and find solutions to them.

I must admit that my observations on many puzzles are contrary to popular beliefs. They are different from the opinions expressed in historical chronicles and official history books. I hope that my observations will be useful in understanding the complex crisis Sri Lanka is currently facing.

I have divided the history of Sri Lanka into two phases as pre-modern and modern. The pre-modern era includes the feudal period from the establishment of early settlements up to the time of Sri Lanka becoming a British colony. The modern age includes the period since Sri Lanka became a British colony.

Emergence of ethnic groups

A logical analysis of historical evidence reveals that Sri Lanka had to a certain extent, been inhabited by a group of people who had possessed some degree of advanced civilisation by the time Vijaya who is believed to be the founder of the Sinhala race reached the island by chance, with his retinue and established his authority on the country.

Findings of archaeological excavations made in the citadel of Anuradhapura by Siran Deraniyagala , the former Director-General of Archaeology, Sri Lanka, have established the existence of a community of people who were civilised to a certain extent and had cultivated cereals like paddy and used pottery items in the 8th century BC, i.e. two centuries prior to the advent of Vijaya and his retinue of people. Perhaps, they must be the tribal groups that the Mahavamsa, the ancient chronicle had referred to as the Yaksha, Naga and Deva communities that lived in Sri Lanka at that time.

While Vijaya and his retinue came to Sri Lanka from North India, the other communities that lived before that, might have migrated from South India. It was from India that we received the technology of the use of iron. The old ancestors who came from South India might have introduced the technology relating to the use of iron in Sri Lanka. The radiometric tests of iron implements excavated from Anuradhapura, have proved that the history of the use of iron in Sri Lanka goes back to the period of 950-800 BC.

It is by the bay of Mannar and Palk Strait that Sri Lanka is separated from the southern tip of Indian peninsula. The distance between the two countries is only 20 miles. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) of USA, the ancient bridge in the Palk Strait between India and Sri Lanka, known as, ‘Rama Sethu’ or Adam’s Bridge is not of natural origin but is man-made. The sea level might have remained lower at that time and migrants from South India to Sri Lanka would have walked across the sea.

The Yakshas, Nagas and Devas, the earliest tribal groups of people can be considered to have migrated from South India. The retinue of people who accompanied Vijaya from North India may have been smaller in their number compared to the number of aboriginal people who lived here. However, Vijaya and his retinue might have been able to emerge as the dominant group in Sri Lanka due to the strong collective power they possessed.

Emergence of religions

During the pre-state era, i.e. the period in which there was no strong political entitity as the State, the tribal communities may have had their leaders to govern them; yet, all of them might not have had a national leader. Similarly, they did not have an organised religion except for animistic beliefs and observances associated with tribal practices. In this backdrop, Buddhism can be said to have complemented these two deficiencies.

If the absence of an organised religion had caused a feeling of emptiness in the minds of the people, Buddhism can be presumed to have contributed immensely in removing it from their minds. At the same time, Buddhism resulted in the enthronement of a king for the country which didn’t have a national leader except tribal leaders.

All the people except the Vedda community embraced Buddhism on account of it being the religion of the king and the royal family and the intellectual appeal of Buddhism. Thus, Buddhism may have functioned as the religion that builds the Sinhalese race and integrates all tribal groups into one ethnic group. In this process, to a large extent, Sri Lanka might have become a country with one religion and one ethnic group.

In the later years, the number of people migrated to Sri Lanka for various reasons, from South India might have increased while most of them retained Hindiuism, their original religion and refrained from converting themselves to Buddhism. This situation might have resulted in disturbing the uniform character of ethnic and religious composition of the society giving way to the emergence of a new ethnic group that speaks Tamil language and worships Hinduism, in addition to the community of Sinhalese Buddhists.

In the early stages of this new development, it might have posed a problem for both the king and the Bhikkhus. This issue might have come to the fore, conspicuously during the long rule of Elara who was neither a Buddhist nor a Sinhalese.

This situation arose not long after the death of King Devanampiyatissa. It had caused to deprive the royal family of its right to rule the northern half of the island while the dignity of the kingship also was diminished. It appears that the Bhikkhus were equally worried as the royal family itself, in regard to this situation. Even though Elara was not an anti-Buddhist, probably, the Bhikkus might not have received the same patronage and recognition that they would have received from Sinhala Buddhist kings.

The fact that Elara was a just king might have posed a problem for the survival of the Bhikkus. The Mahavamsa describes Elara as a king who had upheld justice far and above his natural affection for his own son.

Under the circumstances, both parties, Dutugamunu and the bhikkhus, must have realised that, to defeat a king of the calibre of Elara, in a war against him, it was essential that the people are convinced that the war is waged exclusively for the preservation and progress of Buddhism. Eventually, they were successful in using Buddhism as a powerful weapon and conquer the war against Elara.

King Vijayabahu I and Parakramabahu II

Apparently, the kings who ruled the country after Dutugemunu had not used religion as a weapon, as was done by Dutugemunu, in waging wars against foreign invaders who had usurped the throne. This was probably due to the fact that the kings of the later years had become bi-racial or bi-religious consequent to the society becoming a combination of both.

King Vijayabahu I (1055-1100) was the next king after Dutugemunu to unite the country by waging a war against a powerful foreign invader. Vijayabahu I had to fight not against a king of the calibre of Elara, but against a more powerful and ruthless Chola ruler who had been in power for 77 years and inflicted severe damage to Buddhist temples during his rule. But King Vijayabahu did not turn it into a religious war.

King Parakramabahu II (1236-1278) can be considered the last king to unite the country after waging a war against a powerful foreign invader who had usurped the throne after the king Vijayabahu I. King Parakramabahu II had to wage this war against Kalinga Magha, the most deadly and anti-Buddhist among foreign invaders of Sri Lanka.Even king Parakramabahu II, did not turn the war against Kalinga Magha into a religious war.

Apart from these two kings mentioned above, there were two others who had unified the country. They were Parakramabahu I (1153-1186) and Parakramabahu VI (1415-1467). However, their war endeavours were not against foreign invaders. All four kings who unified the country had built temples and shrines for the benefit of Buddhism; they built Devalas for the benefit of Hinduism. They offered villages to Buddhist temples and Hindu Kovils for their sustenance.

Most of the kings, who ruled Sri Lanka after Dutugemunu, subject to some exceptions, can be considered to have followed two religions to a greater or lesser degree.

The characteristics of religious shrines too, were changed depending on the bi-religious policy adopted by kings. The way the devotees worshipped religious shrines and their observances also changed accordingly. Hindu devalas dedicated for the worship of major Hindu gods such as Shiva and Vishnu and other attendant Hindu deities were built inside Buddhist temples.

The Sinhala Buddhists sought the blessings of Hindu gods while worshipping the Noble Triple Gem of Buddhism. Buddhist monks used to chant pirith in the devalas and confer merits gained on Hindu gods, similar to the way they blessed the king.

South Indian invasions

Sri Lanka being an island separated from India by a narrow strip of sea about 20 miles long, the South Indian kings whenever they resolved to expand their authority over neighbouring states, as a rule, used to invade Sri Lanka also as an extension of their conquest. At that time, subjugation of neighbouring kingdoms was not considered an act of disgrace but a matter of prestige. Even Sri Lanka, despite being a small country was not hesitant to invade selected South Indian states when it was favourable for them.

King Sena 11 (853-887), Parakramabahu I (1153-1186) and Nissankamalla (1187-1196) were among the kings who invaded India. There were many instances in which the South Indian invaders had plundered Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka. Apparently, they had done so to plunder the riches of the wealthy temples and not because they were anti-Buddhist.

There were Sinhala Buddhist kings too, who had plundered the wealth of temples when the State treasury was empty. King Datopatissa (639-650) and King Kassapa I (650-659) and King Vikramabahu I (1111-1132) can be cited as examples for this.

Buddhist relations between South India and Sri Lanka

Despite South Indian invasions and wars waged against them, there remained a strong Buddhist relationship between South India and Sri Lanka. It was to South India that the Buddhist bhikkus of Sri Lanka migrated when Sri Lanka was hit by a severe famine during the reign of King Vatagamini (77 BC). While most of the Buddhist monks of Sri Lanka fled to Ruhuna and Maya Rata during the invasion of Magha, the most prominent bhikkus fled to South India.

Ven. Buddhagosha, Buddhadatta and Dhammapala, the most celebrated authors of Buddhist commentaries were all South Indians. It was from South India that the kings of Sri Lanka got down pious monks to lead the programs of religious reformations when there were no knowledgeable and devout monks in Sri Lanka to undertake them. The Culavamsa states that King Parakramabahu II sent gifts to the Chola Desha and got down the most Venerable Dharmakeerthi Thero to Sri Lanka. It is also recorded in the Culavamsa that King Parakramabahu IV had got down a great Venerable Thero from Chola Deshaya and had him appointed to the position of Rajaguru.

It appears that the invasions from South India had not caused to disturb the reconciliation prevailed between the Buddhists and Hindus or Sinhalese and Tamils in Sri Lanka or create communal disturbances. Racism and religious differences are matters of recent origin associated with the modern age. It was not something that existed in the pre-modern era. But there was a caste system in operation at the time.

Though there were historical chronicles available in the pre-modern era, it was only during the the modern era that they were translated into Sinhala and published for public consumption.

Grandeur of the past

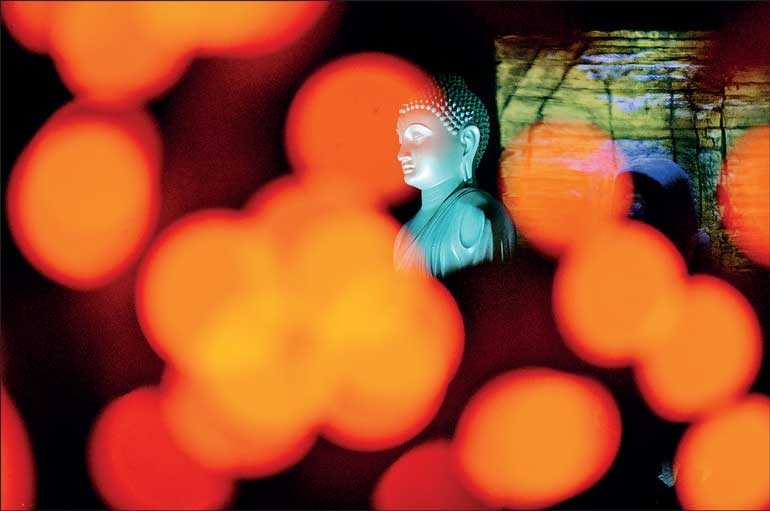

The period in which the Sinhalese Kingdom flourished in the Dry Zone or the Rajarata (up to the early 13th century) can be considered the golden age of Sinhala civilisation. It was during this period that three major cities – Anuradhapura, Sigiriya, and Polonnaruwa emerged. It was during this time that the great stupas of the magnitude of Ruvanvaliseya, Abhayagiriya Chethiya, Rankot Viharaya and Jethavanarama Dagaba and the unique Buddha images of exquisite quality of the Samadhi Buddha, Aukana Buddha and the Buddha statues at Gal Viharaya, Polonnaruwa were constructed.

Sigiriya which can be described as a unique creation in terms of engineering and artistic aspects and the major tanks such as Kala Wewa, Minneriya Weva and Parakrama Samudraya were built at that time. There can be no doubt that Sri Lanka had a well developed and advanced civilisation at that time. There is nothing wrong in being proud of it. But it is important that we must have an objective assessment, and not an overestimation of this civilisation.

Apparently, Sri Lankans do not seem to have a realistic assessment of this heritage. It is mainly due to misinterpretations popularised by leaders like Anagarika Dharmapala. Dharmapala referred to the ancient civilisation of Sri Lanka as the greatest among the old world civilisations. Even the Sri Lankan historians have not rectified this error.

Sri Lanka is not included in the list of the 10 oldest civilisations. This is because the civilisations that were listed had achieved a greater development than the ancient civilisation of Sri Lanka. All these civilisations have served as an important source of new knowledge to the world; in that sense, Sri Lanka has not functioned as a source of new knowledge to the world.

A significant number of books have been written in Sri Lanka during pre-modern times. Apart from the books written on grammar, all other books written had been on Buddhism. Not a single book on mundane subjects such as the objectives of life, the nature of the world, mathematics, philosophy has been written in Sri Lanka.

Except for the Lord Buddha, Sri Lanka was not aware of any other great intellects like Socrates, Plato, Euclid, Archimedes; Aristotle who lived during the century in which the Buddha lived. This can be considered a serious limitation inherent in the historical thinking of Sri Lanka.

Historiography and the bhikkus

Despite such limitations, apart from China, Sri Lanka is the only country which had maintained a long and persistent documented history. The content of Mahavamsa, the earliest and the major chronicle of the country, to a great extent, can be accepted as authentic except for the accounts available for the period upto the time of King Devanampiyatissa (250-210 BC). Though Mahavamsa is an account of the history of Maha Viharaya, it is treated as the major book on the history of Sri Lanka. Despite these limitations, the Bhikkus of Maha Viharaya should be given the honour of documenting the history of Sri Lanka.

In the pre-modern era, the Bhikkhus held a position which was second only to the king. However, during the post Dutugemunu period they did not have much power except to a certain extent, in influencing the activities of the kings. Perhaps, this may be due to misuse of powers by the Bhikkus themselves and the religious tolerance of many Buddhist kings who used to worship Hinduism as well. It was through the Bhikkhus that the king consolidated the loyalty of the Sinhalese Buddhist people. Even though the kings have done their best to support the Bhikkhus in this regard, it is evident that after the Dutugemunu period, the kings had not depended on Bhikkhus in decision-making process.

Finally, the responsibility of maintaining discipline and religiosity of the order of the sangha rested on the king. As far as the king was concerned it appears to be a task more difficult than ruling the country. The Dipavamsa refers to corrupt monks of abhorrent behaviour, who were like decomposed vessels and stinking corpses. Apparently, this situation was largely due to many people choosing priesthood for economic reasons rather than for religious convictions.

Punishing the bhikkhus

In the early days, those who chose priesthood had to live a life full of hardships and austerity compared to lay life. The monks had to live in abodes made in caves. They had to live a life of a mendicant begging from door to door for their food. In the course of time, the kings offered properties to temples in large scale for their existence. As a result, the temple became a property owned institutional system. With these developments the bhikkhus were relieved from being dependent on laity while the laity was made to depend on temples. At the same time, the priesthood had become a way of life which was more comfortable than the difficult life of a lay person.

As Ven Kotagama Wachissara Thero has pointed out, the 15th century saw a great decline in the piety and the virtuosity of priesthood.The bhikkhus did not observe religious rituals. Instead, they got women to cook food for them and were not aware of the practice of ‘pindapatha’-going from door to door begging for food. Even the lay Buddhists didn’t know what ‘pindapatha’ was. What the bhikkhus did most at that time was to manage the temple lands and enjoy the income derived, with their families, children and relatives.

From time to time, the kings held Buddhist councils and chased out corrupt bhikkhus; but they only proved to be temporary measures and not a permanent solution to the problem.

The impious behavior of certain monks seems to have led some kings to act relentlessly against them. King Kanirajanu Tissa (31-34 BC) caused a group of impious monks topple down from a height of a rock at Mihintale. King Gotabhaya (233-266 AD) exiled 60 monks of Abhayagiri Vihara having had their bodies branded with permanent marks of identification.

King Mahasena, acclaimed as the God of Minneriya, regarded the Bhikkus of Maha Viharaya as sinners. The king forbade offering alms to them. They didn’t receive anything in their alms rounds for three consecutive days, compelling them to abandon Anuradhapura and flee to Ruhuna and Hill country. During the reign of King Silamegawanna (619-628) the hands of several monks were severed and ordered to work as the guardians of ponds while one hundred monks were deported from the country.

Though there was a caste system in operation during the pre-modern period, there were no divisions or conflicts between religions and ethnic groups. However, there was a bitter and persistent conflict between two groups of the order of the Sangha. There were incidents of homicides also associated with those conflicts. There were instances of bitter conflicts between kings and monks as well. There had been homicidal incidents also connected with these clashes.