Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Tuesday, 4 May 2021 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

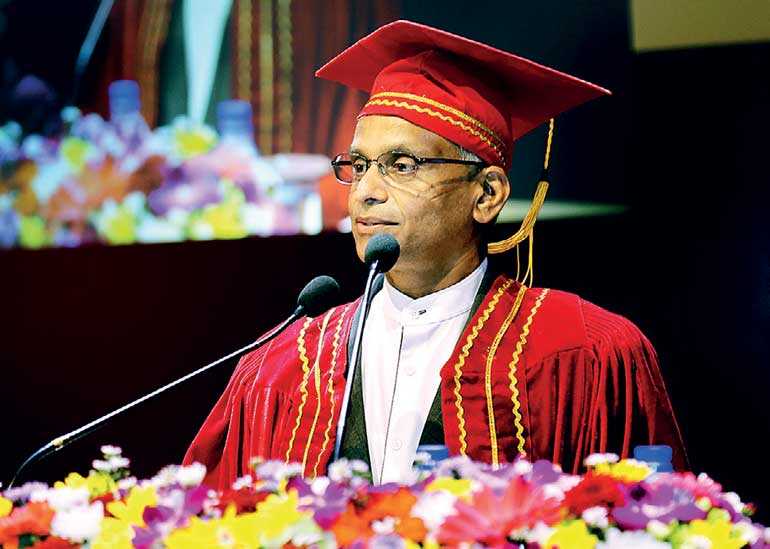

Management consultant Deepal Sooriyaarachchi addressing the PIM Convocation

Following is the address delivered by management consultant, author, trainer and speaker Deepal Sooriyaarachchi at the PIM Convocation on 29 April

Venerable Chancellor, Vice Chancellor, Deans of the University of Sri Jayewardenepura, members of the Board of Management and Board of Study, members of the academic and administrative staff, dear graduates and their well-wishers, ladies and gentlemen, I am indeed grateful and honoured to stand in front of you almost after two decades, since I was where you are today. I recall with gratitude all those who guided and supported me in my MBA journey. If not for them I would not be here today.

First of all, let me congratulate every one of you who graduated today from this prestigious institute. Your loved ones and even your colleagues may have played a role in your success. I salute all of them as well. One of the most powerful lessons I learnt having done the MBA is that, there are hardly any individual achievements. This realisation alone is worth the entire MBA process. It makes me very humble.

As the PIM’s advertising slogan suggests, from today onwards, you are called an MBA or an MPA. In other words, a Master in Business Administration or a Master in Public Administration. Historically a man who has people working for him, especially servants or slaves was called a master. On the other hand, you supposed to have acquired a great degree of skill or proficiency in a particular function or a discipline. Though the first definition may be true in some instances what is relevant most is the second definition. To be a master in management.

With mastering the craft of managing you unleash the potential that is within you to lead teams, organisations and eventually the nation. So, I wish to explore the concept of mastering!

The concept of mastering

In organisations what do we really manage?

However complex the business or the organisation is, all what we do is managing people, processes and policies. All organisational activities can be classified under these three topics.

After studying so much about business and so many theories and models perhaps you may not like me taking such a simplistic view about a business organisation. In managing these three areas all what managers do are making ‘yes’ or ‘no’ decisions and executing them.

A decision is selecting one from among two or more options, based either on past experience or on assumptions about future. And you do that in present moment.

However complex the decision-making process you follow, eventually a manager’s decision has got to be a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’. When making decisions, we always think it is the right decision. Whether it is right or wrong can be determined only in the future. Ideally, the best decisions are those that are right by the enterprise. Ideally a leader must first consider the interest of the enterprise, his or her division and finally self before making the decision. At the national level it should be the nation first, political part next and the individual interest last.

The sathara agathi

Managers or leaders fail to make such decisions when they are conditioned or influenced by four types of biases or extremes. These are called sathara agathi. I wish to explore these biases or agathis we must try to avoid when making decisions so that we can improve the quality of decisions.

The first bias or the agathi is canda/chanda. This means strong attachment, liking or preference. When the decision maker has a strong preference or an attachment towards an option then it prevents seeing any negatives. A decision taken giving priority to self-interest rather than that of the enterprise is a result of this bias. When a manager identifies strongly with a particular option then also the decision can be flawed, for she fails or refuses to see any negatives thereof.

The second agathi is called dvesha or extreme dislike. This can manifest as angry reactions to dislikes in various forms. When such dislikes exist those also prevent us making unbiased decisions. They really blur the view.

The third agathi is called bhaya or fear. Fear can range from fear that comes within due to uncertainty or fear to fail as well as due to various external forces that can cause pressures on the decision maker. This is called decisions made under duress. Such decisions in most instances are not right, that is why they are not accepted to be valid even legally.

The fourth and the final agathi is called moha or ignorance. This can also be defined as lack of required information or basing the decision on mis information. For instance, in Japanese management, they use a concept called gemba and gembatsu to reduce the error due to moha – that is by observing the actual occurrence at the actual place.

If we can avoid these four biases or agathis to a great extent we can make better decisions.

Execution

The second part, and to me the most important part of a decision is execution or implementing the decision. Unless you give your full attention focus and commitment to the process of execution, there is no guarantee that the expected results can be achieved. Managers make seemingly good decisions, but often they fail to execute or implement them wholeheartedly.

After making the decision we tend to identify ourselves with the decision thinking that “this is my decision”. The moment we identify ourselves with a decision we bring our own Ego in to the equation. Then we do not want to change the decision even if the circumstances change. But if a manager has the right attitude about making decisions, that is considering them as actions taken at a certain point in time under certain conditions with certain set of information and assumptions, but when they are not valid anymore then such a smart manager is bold enough to change the decision.

In summary, managers manage people, processes and policies. In doing so they have to make decisions. In making decisions they need to avoid the four agathis – canda, dwesha, bhaya and moha. Once decisions are taken, they must ensure those are implemented and be bold to change them if needed.

Mastering self

There comes another dimension we need to focus since all of this depend on you, the manager, the executive, the leader. That brings us to the sphere of mastering self that goes beyond mastering business. In the subcontinent, for millennia we have been finding ways to master self.

All our faculties are directed outside, thus it is nothing but natural most our explorations are about external world and others. We are so busy in responding to the demands of these faculties so much so we forget to look inward unless there is some crisis. Since these faculties command our attention, they are also referred as indriya. It comes from the word indra, it means the ruler, chief, or master. How true that we are driven by our faculties.

Unless we take the same interest, that we take to master business management to manage our selves, one day we end up paying dearly. The significance of this is beautifully articulated in Dhammapada, the most popular collection of sayings of Buddha. It says:

Yo sahassam sahassena

Sangàme mànuse jine

Ekanca jeyya attànam

Sa ce sangàma juttamo

(Though one should conquer a million men in battlefield, yet he, indeed, is the noblest victor who has conquered himself.)

Paying attention

Whether it is in business or in life, if one wants to master, one has observe the current situation; to observe one must pay attention. Paying attention is hindered when the attention moves on to other objects or phenomena. This is what we call distraction.

Actually, there is nothing that can be called distraction but the change in the object of attention. This is one of our biggest challenges today. As Herbert Simon, the Nobel award-winning Economist said in 1977, “What information consumes is the attention of recipients. Hence, a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.”

To observe one needs to pay attention, attention is to focus, to focus one needs to have silence, silence means lack of distraction. It is not the absence of external sounds or other stimuli, but a state of being unmoved by different external stimuli or thoughts that pop up endlessly. True observation is not getting engrossed and loosing perspective but to be able to observe a phenomenon without getting involved. That means observing devoid of biases, such as like and dislike.

This needs patience, and sharpness of awareness. One can observe only what happens here and now. Eventually the observer can observe the process of observation leading into a deeper realisation of true nature of the observer herself. That the observer too is in a constant flux. Such a person is fully aware and alive to what goes on here and now. This level of inner mastery is a result of an enormous amount of energy and a deep level of stillness. That realisation is the true unleashing of potential of the person.

Although the MBA or MPA is related to the professional aspect of your life, I do not think life can be viewed in such a compartmentalised manner as personal life and professional life. These are only different roles we play. Thus, life must be viewed as a cohesive whole. Whether professional or otherwise in most instances we seem to know what to do but there appears to be a gap between what we know and what we do. Mastering is about reducing that gap. To master, improve your observation.

Mastering life

To illustrate this let me share a very interesting Zen story.

A Samurai father wanted to endow his ancestral sword to one of his sons. Obviously, it had to be to the best swordsman among them, the one who had mastered the craft. To select the best, the father decided to set a ploy.

He placed a pillow between the door and the ceiling. Whenever someone opened the door, the pillow would fall. Then he asked his eldest son to enter the room. As planned the pillow fell but the son was very fast, he pulled the sword and hit the pillow before it reached the level of his knee. The father said, “You are very good, but not yet a master.”

Then it was the turn of the second son. The same thing happened but he was much faster and could cut the pillow into two even before it reached the level of his chest. The father said, “I’m impressed but you too are not yet a master.”

The youngest son knocked on the door and before opening the door he checked it for dangers and found the pillow, took it into his hand and placed it away. Obviously, that is the sign of a true samurai. To win even without fighting. This level of mastery comes not only by studying and practicing a certain discipline but reaching a certain level mastery over self.

Now that you have gained a certain level of mastery in management, may I invite you to commence the process of mastering life? In that I wish and assure you an interesting journey.