Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Wednesday, 3 July 2024 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

If the executive presidency is not abolished, if the PTA stays (or is replaced by something as bad or even worse), if militarisation is not rolled back, if political monks continue to dictate terms and conditions to the country, what would system-change look like?

By Tisaranee Gunasekara

“The night is an open book. But the world beyond the night remains a mystery.” – Louise Gluck (Before the Storm)

Sri Lanka always ranks low in the World Happiness Index; 128 out of 148 in 2024 (we rank 48 in Global Militarisation Index though, and possess the 17th largest military in the world). We are also a gloomy lot in terms of how we see the country’s future. According to a new Institute of Health Policy (IHP) poll, in May 2024, 80% of Lankan adults thought the country was heading in the wrong direction. Just 4% thought the country was on the right path; a slight improvement compared to February 2024 when 0% felt the country was on the correct track (https://ihp.lk/research-updates/number-sri-lankans-thinking-country-heading-wrong-direction-continues-increase).

Sri Lanka always ranks low in the World Happiness Index; 128 out of 148 in 2024 (we rank 48 in Global Militarisation Index though, and possess the 17th largest military in the world). We are also a gloomy lot in terms of how we see the country’s future. According to a new Institute of Health Policy (IHP) poll, in May 2024, 80% of Lankan adults thought the country was heading in the wrong direction. Just 4% thought the country was on the right path; a slight improvement compared to February 2024 when 0% felt the country was on the correct track (https://ihp.lk/research-updates/number-sri-lankans-thinking-country-heading-wrong-direction-continues-increase).

So feelings. In actual terms, we are in a better place than we were two years ago, in that calamitous and momentous July 2022. In June 2022, only 1% of Lankan adults felt that the country was headed in the right direction; 80% thought the country was headed the wrong way. Understandable, given the total collapse of everyday life. There are no mile-long queues now, or crippling shortages, yet the feel-bad factor remains.

Lankan economy began to record positive growth in the last two quarters of 2023. The upward trend continued in the first quarter of 2024, with a growth rate of 5.3%. The economy has grown over three consecutive quarters; not a fluke then, but a welcome sign of recovery. No mean achievement, given where we were in that historic July two years ago.

2024 first quarter growth occurred across multiple sectors, from agriculture and industry to construction and services. Yet, the areas of contraction are concerning, especially information and communication (which includes the IT sector) and education, human health, and social welfare activities. Growth yes, yet severely imbalanced in its benefits; iniquitous growth, resulting from policy choices. This slant, for example, was in-your-face evident in the latest fuel price reductions. No decrease in kerosene oil or standard diesel prices; Octane 92 petrol reduced by Rs. 11; Octane 95 petrol cut by Rs. 41 and Super Diesel by Rs. 22. So no relief for the poor dependent on kerosene oil for cooking and illumination, including many of the 1 million plus families who lost electricity connections in 2023 due to non-payment. And a huge bonanza for those who own high-end vehicles, many of them fuel-guzzlers.

Around 25% of Lankans live below the poverty line. About 55.7% of Lankans (more than half the population) are multi-dimensionally vulnerable. As the World Bank warned in its April 2024 Sri Lanka Development Update, “Households have adopted risky coping strategies to deal with lower incomes and price pressures, including using savings, taking on more debt, and limiting their diets. Food insecurity rose during the second half of 2023, with 24% of households being food insecure” (https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/srilanka/publication/sri-lanka-development-update-2024). They need help most, yet are being left in largely the lurch.

President Wickremesinghe’s Urumaya program is a leap in the right direction, and a long overdue one. He didn’t exaggerate when he called it ‘revolutionary’. As with taxation (correcting the gross imbalance between direct and indirect taxes, an iniquitous legacy from before Independence), here too he is on the right side of history. History would acknowledge it, but that is in the future. In the here and now, Urumaya is not enough to protect the vulnerable, alleviate national gloom, and save his presidency. Even if the election becomes a three-way battle, as in France, neither of the two front runners will be named Ranil Wickremesinghe.

The other July

Ceylon at Independence was a better and a worse place than Sri Lanka today. It was a worse place in terms of economics, and the material living standards of a majority of Lankans.

Let’s stick to available data, rather than manufactured outrage. In 1948, our average life expectancy was 54 years, compared to more than 77 years in 2021. Maternal mortality in 1948 was 830 per 100,000 live births to 29 per 100,000 live births in 2020. In 1950, infant mortality was 82 per 1,000 live births compared to 6.4 today. Primary and secondary school enrolment ratio was 54% then compared to around 95% today. These are significant progresses by any standards.

But Sri Lanka today is a much worse place to live in terms of safety and security than Ceylon at Independence, far more violent, far more militarised, a place of guns, bloodshed, and unimaginably brutal crimes. That decline in public safety and ethics can be traced back primarily to our persistent inability to manage inter-ethnic/religious relations. It was no accident but the result of a deliberate policy of exclusion, marginalisation, and discrimination which began in the year dot with the disenfranchisement of plantation Tamils.

Much is being said about 76 wasted years, yet very little about the ethno-religious politics which was the number one cause of that wasting.

July marks two critical anniversaries – the 2022 ousting of Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the anti-Tamil pogrom of 1983.

July marks two critical anniversaries – the 2022 ousting of Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the anti-Tamil pogrom of 1983.

On 23 July 1983, the LTTE carried out the Four Four Bravo operation. 13 soldiers were killed in that ambushing of an army patrol, a spectacular feat for a small struggling guerrilla organisation. But Velupillai Prabhakaran was in no celebratory mood. Less than a fortnight previously, the organisation’s de facto deputy leader Seelan, surprised in his hideout by the army and unable to flee due to a previous injury, had ordered his comrades to shoot him. In the Four Four Bravo operation, Chellakilli, a key Tiger operative, died accidently while operating the mine. When Prabhakaran was told about the loss, “he began to wail. Seeing him, almost everyone began crying.” (Tigers of Sri Lanka: From Boys to Guerrillas – MR Narayan Swami).

Had there been no Black July, the Four Four Bravo operation might have been both the apogee and swan song of the Tigers. The pogrom of 83 saved the LTTE from oblivion, catapulting it from a nondescript armed organisation to one of the most effective and fearsome guerrilla armies in the world.

It is customary to blame the rulers in particular and elites in general for everything that went wrong with and in Ceylon/Sri Lanka. The responsibility is theirs, but not exclusively. A large part of the responsibility also belongs to political monks who used the power-hunger of rulers and would-be rulers to impose Sinhala-Buddhist supremacist agendas on successive governments. Without Sinhala Only, there would have been no Black July and no Eelam War. As two Sabaragamuwa University academics, Pradeep Uluwaduge and Saman Handaragama, explain in a 2019 research paper, “Especially, from the 1950-60’s, political interference by Buddhist monks contributed considerably to the sundering of inter-racial coexistence. Buddhist monks believed that the rights of all communities will be protected if Sinhala-Buddhists are dominant culturally, religiously, institutionally, economically, politically, and linguistically… Monks are expected to value non-violence, yet their actions exacerbated lack of trust and suspicion among ethnic communities. Their preaching, which do not belong in the Buddhist canon, caused governments to move in wrong direction. That error remains uncorrected even now” (https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335788806_Religion_and_Politics – translation mine).

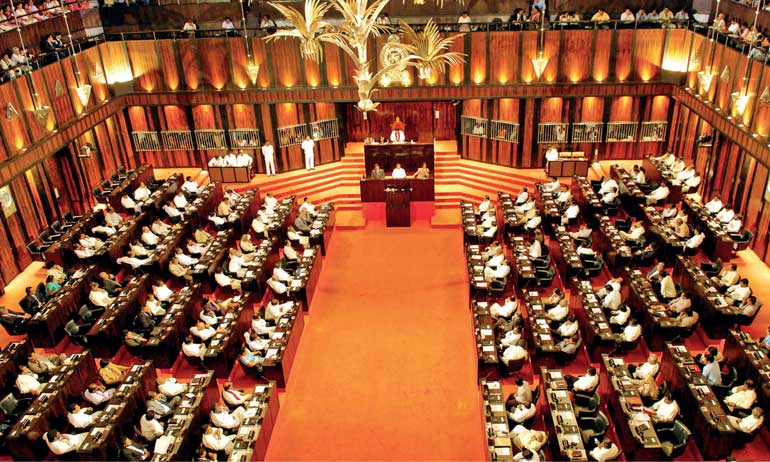

In 2022, President Wickremesinghe, speaking in Parliament, asked monks to stick to their job (instead of dabbling in politics). Intentionally or not, he was revisiting a battle that commenced on the cusp of Independence. The casus belli was the question whether monks should be politically active or limit themselves to spiritual and social (rural development) activities. The antagonists were centred round Vidyodaya and Vidyalankara pirivenas. The supposedly secular left backed the Vidyalankara monks who claimed that Bhikkus should be politically active and provide leadership to the nation. The ‘reactionary’ UNP supported the Vidyodaya position which opposed the involvement of monks in politics.

From this battle was born that dangerous misnomer, Progressive Monk. As 1948 gave into 1956, progressive monk became the driving force in the ‘struggle’ to save Lanka for its only true owners, Sinhala-Buddhists. Political monks were behind almost all discriminatory and divisive legislations and actions 1956 onwards. They also played a seminal role in stymying attempts by successive governments to achieve ethno-religious reconciliation, from the B-C Pact to the Indo Lanka Accord.

When President Wickremesinghe expressed his intention of implementing the 13th Amendment in full (like many of his promises, it was broken), Agalakada Sirisumana thero, a professor in the Sinhala Department of the Colombo University, said, “Leaders cannot be allowed to do such things the way they want. If they do, only the monks can throw you out on your ear.” Monks as not just king-makers but also power behind the throne, de facto rulers. When Ranil Wickremesinghe postponed the LG polls indefinitely, the monk organisation aligned to the JVP/NPP asked the chief prelates to issue a Sangha Order to the President Wickremesinghe dictating him to hold elections.

Bhikku politics is a key causative factor of the national malaise and no system-change for the better is possible if political monks continue to propose and dispose. As Prof. Chandra Munasinghe of the Buddhist and Pali University said, “A group of monks deviating from the goals of monkhood has come into being. The main reason for this deviation is politics… People, politicians, and monks are all on the wrong track. Travelling on the wrong path has become normalised… Flower basket politics, temple politics remains relevant. If this doesn’t change, we are headed down to abyss” (https://www.bbc.com/sinhala/articles/cd11r2vdkydo).

Bhikku politics is a key causative factor of the national malaise and no system-change for the better is possible if political monks continue to propose and dispose. As Prof. Chandra Munasinghe of the Buddhist and Pali University said, “A group of monks deviating from the goals of monkhood has come into being. The main reason for this deviation is politics… People, politicians, and monks are all on the wrong track. Travelling on the wrong path has become normalised… Flower basket politics, temple politics remains relevant. If this doesn’t change, we are headed down to abyss” (https://www.bbc.com/sinhala/articles/cd11r2vdkydo).

Dissecting change

The Presidential election is likely to usher in a President Sajith Premadasa or a President Anura Kumara Dissanayake.

Both are big on change. So what would change on their watch look like?

“If men suddenly see a child about to fall into a well, they will, without exception, experience a sense of alarm and distress,” wrote the 2nd BCE philosopher, Mencius. Unless the incident happens during a contestation between Us and Them and the child happens to belong to Them. So when Gotabaya Rajapaksa pardoned army sergeant Sunil Rathnayake, there was barely a hum from the South (no statements from the UNP, the new SJB or the JVP/NPP) even though the man was a cold-blooded killer and his eight victims included a five-year old child and his brothers, aged 13 and 15. “All the eight deceased persons had sustained the identical fatal injury, a cut on the neck inflicted from behind, as disclosed by the medical evidence,” wrote Justice Buvaneka Aluvihare, confirming Sunil Rathnayake’s murder conviction (http://www.supremecourt.lk/images/documents/sc_tab_1_2016.pdf).

Made to kneel, throats slit from behind. Our silence on the pardoning of such a monstrous murderer happened just four years ago. That silence cannot be blamed on rulers or elites. It comes from who we are. If such attitudes remain unquestioned, what system-change?

Forget the 13th Amendment. What would the new president do about the continued militarisation of the North and parts of East? In 2022, 14 out of 21 Lankan army divisions were stationed in the North. Mullaitivu district reportedly has 65,000 military personnel, one soldier for every two civilians. Will the new president de-militarise the North, scaling down camps and military-owned businesses, and returning the still-occupied land to their original owners? Will he take a stance against the military-monk nexus which seeks to claim the North and parts of East for Sinhala-Buddhism one bo sapling/Buddha statue at a time? Will he prevent monks from using archaeology to drive Tamils and Muslims from their lands?

What will the new president do about the size of the military and about defence expenditure? The gargantuan military maintained at a massive cost failed to prevent the Easter Sunday massacre. So what exactly are we defending and from who?

What will the new president do about the size of the military and about defence expenditure? The gargantuan military maintained at a massive cost failed to prevent the Easter Sunday massacre. So what exactly are we defending and from who?

What will the new government do about the PTA, which failed to prevent the growth of a small Tamil insurgency into a full scale war, and failed to stop a handful of suicide killers from bombing churches and hotels at will? Keep it? Or change it? If so, how? What will happen to the draconian Online Safety Act under a new dispensation?

What about the involvement of monks in politics? The JVP/NPP is organising monks island-wide. Sajith Premadasa has set up a Sangha Advisory Council. Will either party work to reduce monk involvement in politics – a greater and more consequential problem than corruption – or not? (Incidentally, political monks were pioneers in corruption as well; Mapitigama Buddharikkhita thero fell out with SWRD Bandaranaike because the latter refused to give a shipping contract to a crony of the political monk).

What about the executive presidency, which has failed manifestly to achieve either stability or development? In fact, without the powers of the executive presidency, Gotabaya Rajapaksa would not have been able to drive a lower-middle-income country into chaotic bankruptcy in just two and a half years. Tying the fate of the executive presidency to a brand new constitution is not the way to its abolishment but to its perpetuity. The scrapping of the executive presidency might have to be done via a constitutional amendment subsequent to a two-thirds majority in Parliament and a referendum.

If the executive presidency is not abolished, if the PTA stays (or is replaced by something as bad or even worse), if militarisation is not rolled back, if political monks continue to dictate terms and conditions to the country, what would system-change look like? Will the new light be any different from familiar darkness?