Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Saturday, 17 February 2024 00:22 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

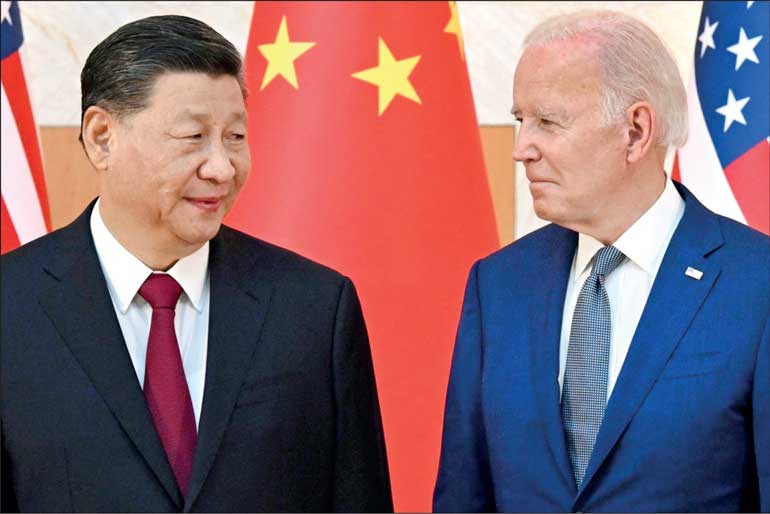

With the rise of China and much of Asia, the US no longer dominates the world economy

In the 16th century, Spain became the first global empire. Spain flexed its military prowess, but also prospered culturally, architecturally, and formulated ground-breaking ideas on natural law, sovereignty, international law and economics. They even themselves philosophically questioned the validity of imperialism!

In the 16th century, Spain became the first global empire. Spain flexed its military prowess, but also prospered culturally, architecturally, and formulated ground-breaking ideas on natural law, sovereignty, international law and economics. They even themselves philosophically questioned the validity of imperialism!

By the 19th century, Britain became a global hegemon. This was inaugurated by the British Empire’s earlier defeat of the Spanish Armada coinciding with the flowering of the Elizabethan age, vast voyages of exploration and soon, the greatest navy the world had seen. This continued through Victorian England and the industrial revolution, until two world wars displaced an Empire on which once “the sun never set.”

After World War 2, the United States took over as the new global hegemon, becoming the world’s financier and armoury and also a welcoming hub for the world’s talent and enterprise. Now, America’s power is fading, and some Americans fear that China will be the next hegemon. They are likely incorrect. In fact, we are moving to a post-hegemonic world.

Driving geopolitical change

To see why, let us understand the drivers of geopolitical change.

How did the United Kingdom expand its strengthening global dominance from around 1815-1914? In the 1770s, James Watt, working at the University of Glasgow, produced a highly efficient steam engine. Britain thereafter harnessed the low-cost steam power and its vast coal reserves to build the world’s pre-eminent modern industrial economy and the world’s first modern industrial military.

Britain’s steam-powered navy ruled the seas. England’s vast empire also established their language as the global currency for the world’s business and trade and even artistic exchange in terms of books, architecture, theatre and more. There is a cultural aspect to hegemony that cannot be ignored.

Britain’s innovations gave it roughly a 75-year lead over its closest competitors, the US and Germany. By the end of the 19th century, the US and Germany, rich with their own coal, had adopted, adapted, and in many cases, surpassed Britain’s industrial innovations. Like all empires, Britain ran up debt, became over-extended and prone to be drawn into expansive and depleting wars.

Between 1914 and 1945, the British Empire was mortally wounded by two world wars. The US, protected by two oceans, surged in industrial power and technology. By 1945, Britain’s empire was broken, while America had through the stimulus of war production and retaining a country not devastated by war, had recovered from the Great Depression and flourished.

Between 1914 and 1945, the British Empire was mortally wounded by two world wars. The US, protected by two oceans, surged in industrial power and technology. By 1945, Britain’s empire was broken, while America had through the stimulus of war production and retaining a country not devastated by war, had recovered from the Great Depression and flourished.

To secure its new hegemony, the US established hundreds of overseas military bases in around 80 countries, and the Central Intelligence Agency, established in 1947, in a less savoury counterpart to this, led coups, assassinations and insurrections against governments resisting US power.

China and more

China’s rise between 1980 and 2020 recalls the rise of Germany and the US in the late 19th century, but with a major difference. Catching up these days can be much faster than in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Technology spreads very rapidly to well-organised countries such as today’s China, which successfully promoted quality education and the spread of science and technology. China also has the population and size to reinforce its economic capability and overall heft. It also operates in the one of the most successful economic regions in the world, initially catalysed by Japan.

There is nothing nefarious about the rapid spread of technology. On the contrary, the rapid spread of technology raises global living standards and spurs further innovations. As long as you have educated talent and most of your expenditure doesn’t go towards an incompetent, bloated government. Japan demonstrated the trifecta of technology/institutional health/education, and evangelised an entire region, eventually through the quality revolution, much of the planet.

China’s rise has been good not only for China but for the world. Economic advancement is a positive-sum game, not a zero-sum struggle. However Chinese institutions have struggled to keep pace with the economic development underway, and the autonomy of individual citizens has never been as much of a focal point of this Confucian culture.

With the rise of China and much of Asia, the US no longer dominates the world economy. More generally, the economic predominance of the North Atlantic region — Western Europe, the US and Canada — is coming to an end as the rest of the world closes the gaps in education, technology, innovation and productivity.

With the rise of China and much of Asia, the US no longer dominates the world economy. More generally, the economic predominance of the North Atlantic region — Western Europe, the US and Canada — is coming to an end as the rest of the world closes the gaps in education, technology, innovation and productivity.

And also as the governing institutions of these North Atlantic countries seem to no longer represent the popular will and have been mortgaged to commercial interests, lobbyists and other power brokers. The high notes of liberty have increasingly been playing second fiddle to the crassness of aggrandising self-interest.

And far from breaking up monopolies and promoting real competitiveness, much of modern economics is about underwriting them.

The next era

We are therefore, with the sundown of the moral and institutional high ground, reaching the end of centuries of Western dominance. Starting with Columbus’ voyages from Europe to the Americas, looking for trade routes, Columbus inadvertently rediscovered a new continent, that was to become, through colonisation, another cradle for manifestations of Western culture. But the country once hatched and legalised, kept spreading. All the way to the Pacific Ocean, and so Asia and Europe commingled.

American politicians tremble that China will become the new global hegemon, but they should calm down and look at the facts. Throughout its long history of more than 2,200 years as a unified state, China has never sought an overseas empire. The only time that China tried — and failed — to invade Japan was 750 years ago, when China was under Mongol rule! And despite saber rattling galore, it has never made successful inroads in Vietnam in the modern era either. That should have been a warning to the French too and the US, alas no.

Nor could China become the new global hegemon even if it wanted — which it does not. There are three main reasons. First, technological upgrading is boosting not only China but most of the world. India, for example, was roughly at the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita income of China 15 years ago, but is now growing faster than China, and has greater access to today’s power bloc via English. Just behind India will likely come Africa’s era of rapid catch-up growth, there are few geographical or “asset” based barriers to this.

Second, China’s population peaked in 2023 and is starting to decline. Because of the coming decline in China’s population, China’s share of world output (measured at purchasing-power-adjusted prices, and according to International Monetary Fund data) will probably reach its maximum in the next few years, at roughly 20% of world output and will likely gradually decline in the 2030s and onward to around 17% by 2050.

India’s global share of GDP, by contrast, will likely rise from around 7% today to perhaps 13% in 2050. The US share of the world economy will is likely to diminish from around 15% of GDP in 2023 to somewhere around 10% in 2050.

India’s global share of GDP, by contrast, will likely rise from around 7% today to perhaps 13% in 2050. The US share of the world economy will is likely to diminish from around 15% of GDP in 2023 to somewhere around 10% in 2050.

Africa will also likely become a much bigger part of the world economy by mid-century because of the combination of a rapid rise of GDP per person and a burgeoning population. In 2023, Africa accounted for roughly 5% of the world economy. By 2050, that share is likely to rise to somewhere around 20%, as Africa’s share of world population rises from 18% today to 26% in 2050.

And so, for all the personal repercussions it may have had, Imran Khan of Pakistan was perhaps wise to refuse to repudiate China and Russia and demonstrate unqualified fealty to Washington’s political and economic playbook. Certainly, the recent election results there in Pakistan show that he successfully tapped into widescale national sentiment.

The third reason is that China culturally does not enjoy the swagger and centrality of infusing the world with their cultural magic. Not in the way the grand colonisers did, certainly not the way the US does as a purveyor of the world’s popular culture. Thin gruel it may be, but it is ubiquitous.

The Chinese consider their culture and their norms to be inscrutable, and they are not looking to “socialise” the world to behave like them, or become like them, to take on their music, or art or culture. Even their cuisine, lands everywhere and adapts to local tastes rather than demanding allegiance to its origins as French and even Japanese cuisine do.

To China, their culture and ethos are treasures that require you to be inculcated and immersed. They are not readily transmissible. The Chinese prefer to turn inward rather than reach out to invite others to gain their cultural reflexes or paradigmatic default settings.

Hence, they would enjoy being economically pre-eminent in a multi-polar world, where others can share influence and stimulus. The US believes everyone wishes they could be American, and in some ways, and for some time, we Americans were right. And then we forgot about why that was the case.

It was the energising and welcoming sense of meritocracy, being able to carve out your own life and dreams, a legal dedication to enterprise and a social commitment to human flourishing that was a signature of national identity. Today, and we can pray it is not irreversible, too much of that has become commercialised, polarised and increasingly incongruent and banal.

The Chinese have no such expectation, and it certainly is not an aspiration. “You cannot be us” and we don’t want you to be. However, we are happy to interact, to trade with you, to have you profit us, and perhaps look in awe at our prowess and achievements. We will partner with you Sri Lanka and Pakistan and Qatar and Russia and whoever else can help us economically expand and blossom.

President Joe Biden, an elderly man with reveries of the past, continues to assert that “American leadership is what holds the world together,” even as the US is ever more isolated diplomatically, and as the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and more) nations overtake the G7 (Group of Seven) in economic size and global influence. The American idea may still hold sway, but alas not its operating reality today.

President Joe Biden, an elderly man with reveries of the past, continues to assert that “American leadership is what holds the world together,” even as the US is ever more isolated diplomatically, and as the Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, and more) nations overtake the G7 (Group of Seven) in economic size and global influence. The American idea may still hold sway, but alas not its operating reality today.

The US continues to push its hegemonic aspirations by trying to expand NATO to Ukraine, thereby provoking dangerous, bloody and costly conflicts with Russia, almost casually forgetting promises made and positions taken by elder statesmen like then Secretary of State James Baker after the Berlin Wall fell.

This was part of what seduced Gorbachev, and it’s later betrayal, was part of what delegitimised a key part of his legacy (US Secretary of State James Baker’s famous “not one inch eastward” assurance about NATO expansion in his meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, was part of a cascade of assurances about Soviet security given by Western leaders to Gorbachev and other Soviet officials throughout the process of German unification in 1990 and on into 1991, according to declassified US, Soviet, German, British and French documents posted by the National Security Archive at George Washington University).

Post hegemony

Similarly, the US continues to arm Taiwan despite China’s strenuous objections and US promises dating back 40 years that the US would phase out military support to Taiwan. I neither applaud nor decry this, but it is not how you build partnerships or bridges. Perhaps there is a strategic influencing role to be better leveraged here instead, but that needs some rapport building and credibility building first.

America’s hegemonic aspirations are neither broadly accepted by the rest of the world and are less and less realistic in view of America’s waning relative power. Rather than scheming pointlessly to prolong hegemonic dominance that no longer exists, most of the US population would rather aim for greater investment at home and targeted global cooperation as the true basis for US security. And diverting energies and imagination once more to some less martial aspirations and to more Edisonian aims would be a magnificent step.

And so, while the US reconsiders how many military bases do you need in the 21st century and for what purpose, as elections hit around the world, perhaps a global passion for finding our respective genius nationally and sharing it, building the productive capability of our nations, can be cultivated anew, stoked again, liberated from the war drums and pharma-pandemic delusions.

And so it will be imagination, initiative, welcoming variety, providing institutional fairness once more, having an irrepressible faith in progress, that perhaps a freshly inspired US can help lead – and perhaps it can help ignite similar passion in other cultures who can be stirred and stimulated in line with their own traditions and dreams.

The alternative is to watch as fresh genocides are hatched, mindless wars proliferated, idiotic pharma scams rolled out, surveillance and censorship proliferate, and autonomy is whittled down while we babble vacuities under pretentious labels.

Thomas Paine, as the American Republic was being conjured, wrote, “THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.” So many countries need such love, our future depends on it.

Thomas Paine, as the American Republic was being conjured, wrote, “THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman.” So many countries need such love, our future depends on it.

(The writer is the founder and CEO of EPL Global and founder of Sensei Lanka, a global consultant with over 30 years strategic leadership experience and now, since March 2020, a globally recognised COVID researcher and commentator.)