Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Monday, 21 October 2024 00:45 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake

Sajith Premadasa

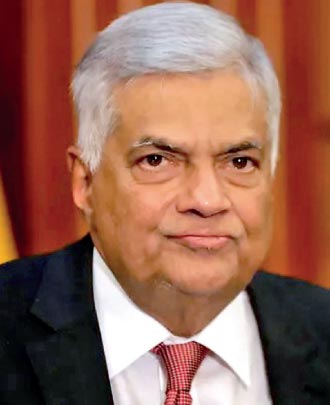

Ranil Wickremesinghe

Daron Acemoglu

Simon Johnson

James Robinson

|

Announcement of Nobel Prize for economic sciences

Announcement of Nobel Prize for economic sciences

Last week, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the Sveriges Riksbank (Central Bank of Sweden) instituted Nobel Memorial Prize for Economic Sciences to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson abbreviated as AJR. The citation said that they are being recognised for this high award for their breakthrough studies of how institutions are formed and how they affect prosperity. The first two are presently located at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the last one at the University of Chicago, though their undergraduate and graduate education in economics had been completed in prestigious UK universities like Oxford, Manchester, York, Sheffield, and LSE.

Importance of institutional economics

The work recognised for this award is the research done by these three economists over several decades on the role of institutions in generating prosperity to nations. The main work by the trio had been originally published in the American Economic Review and later reproduced in MIT economics1. This paper was of quantitative orientation but later, Acemoglu and Robinson published the results in a book titled ‘Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty’ meant for ordinary readers.

There have been several other major publications by them on the same theme: Economic Origins of Democracy and Dictatorship (2005) presenting a framework for creating and consolidating democracy as against dictatorship and The Narrow Corridor (2019) analysing why liberty loses to authoritarianism by Acemoglu and Robinson, and Power and Progress (2023) exploring the relation between technology and prosperity by Acemoglu and Johnson. Anyone wishing to learn of the economic thinking of the trio should master all these books and numerous scholarly papers they have published.

Institutions in economics: a multidimensional value system

They were recognised for the Nobel award in 2024 for their contribution to identify how institutions lead to economic prosperity or adversity depending on the type of institutions that you have in a country. However, institutional economics was explored by another Nobel Laureate in economics, Douglas North who received this coveted prize in 1993, in a book titled ‘Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance’ published in 19902.

In economics, institutions are not merely the formal organisations that we find in contemporary society. They are broader in scope and have a socio-cultural value dimension. According to North, institutions are any form of formal or informal limitation or restriction that human beings devise to shape human interaction3. Formal constraints are rules that humans follow when interacting with others; informal are societal conventions and codes of behaviour that they adhere to when doing societal dealings. In Sri Lanka, a formal institutional rule maybe ‘not stealing (or stealing)’ from your neighbour. An informal code maybe ‘wearing white when visiting a Buddhist temple’ or ‘offering an ata pirikara or eight-type requisites when visiting a Chief Buddhist monk for blessings’.

North says that those institutions can be created anew or allowed to evolve over time. They can, therefore, be what individuals are prohibited to do in one circumstance or what they are permitted to in another. Therefore, we can broadly say institutions in economics are values, beliefs, behavioural patterns, and accepted norms of people in contemporary societies that may differ from society to society and from time to time. It is a multidimensional institutional framework.

Economic institutions and property rights

Out of this multidimensional institutional framework, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson or AJR for short have identified economic institutions, geography, and culture as the contributors to long-run growth in countries and consequently the reasons for the difference in economic prosperity among them4. Of them, economic institutions are more relevant5. According to the trio, these institutions are more relevant because they influence the incentive systems through the protection of property rights.

Property rights, according to economists, are the powers which people get to use their labour including knowledge or physical assets in the best way they think they could get the highest benefit without the fear of being expropriated by someone against their consent. Any transfer of them to another should be in a market transaction in which both parties should agree to the terms like compensation, quantity, or quality, etc.

Without property rights, there is no incentive for people to acquire physical or human capital or adopt new technologies to improve the productivity in the economy. In this way, economic institutions help economies to allocate resources for the best use by ensuring the receipt of earnings from their investment without being used by another. AJR say that the consequential innovation and efficiency will help societies to prosper continuously. Hence, societies with a good economic institutional framework will prosper, while others lag.

Inclusive and extractive institutions

Good economic institutions are called inclusive economic institutions which share the wealth of a nation among people equitably. Bad ones are called extractive economic institutions because they appropriate (or more correctly misappropriate) the nation’s wealth to a select group. A country will have inclusive economic institutions if that country’s political system is guided by democratic ethics and the norms of good governance that includes the observance of the rule of law. In the opposite, a political system with dictatorial or authoritative orientation that upholds the rule of men instead of the rule of law and disregards accountability, a key component in good governance norms, will foster extractive institutions. Such a nation will have low economic prosperity and hence be a laggard in the global drive for prosperity.

Sri Lanka, an extractive institution

According to econometric correlations which AJR have calculated, Sri Lanka ranks at about 6 on a scale of 10 marking the average protection against risk of expropriation during 1985-95. Sri Lanka’s per capita GDP assessed via purchasing power parity in 1995 had been at around 7 on a scale of 10. Sri Lanka’s ranking is better than the countries like Haiti, Uganda, or Bangladesh. But what is to be noted is that countries like Singapore, Luxemburg, or Norway are close to 10 on both scales.

Public outrage against extractive institutions in Sri Lanka

Thus, Sri Lanka had had mostly extractive institutions in the past meaning that the national wealth had been misappropriated by a select few. This is evident from the inequitable income distribution in the country. Throughout the post-independence period, the wealthiest representing the top 20% of income earners had got about a half of the income, while the poorest 20% had got only about 5%.

Thus, Sri Lanka had had in the past and is having today a ‘K’ type economic growth in which the rich have become richer, and the poor have become poorer. This has led to the general belief that all the political leaders in Sri Lanka during the post-independence period had been extractive institutions concerned about their own prosperity and powerbase. This belief is also an institution in the multi-dimensional institutional framework proposed by Douglas North.

AKD: shrewd capitalisation of public outrage

In the recently concluded Presidential election, Anura Kumara Dissanayake or AKD shrewdly capitalised on this widely held belief that all those who had been in power in the past had been corrupt and, therefore, extractive. This was a very strong entry point to a population which had been driven to misery by the harsh economic conditions of the day. High cost of living had reduced their real consumption, investment, and savings to a half. High taxes, imposed under the IMF’s prescription of resolving budgetary issues by increasing revenue, known formally as ‘revenue based fiscal consolidation’, had further reduced the money they can spend, called the disposable income. The shrinking or low-growth economy had deprived them of income earning opportunities. All these had strengthened the belief that all those who had been in power were extractive by nature.

RW’s wrong approach

Ranil Wickremesinghe or RW sought to win the election by telling the people that he was a miraculous problem solver and without him in power, the country would descend to the worst economic conditions which it had a few years back. But his actions – lack of accountability, non-observance of the rule of law, overt and covert support for those who had been accused of corruption, disregard of the judicial intervention to correct the wrongs, making elections disappear via flimsy excuses and many more – had already proved himself to be an extractive institution. The political group which supported him too had been branded as extractive.

SP branded as a part of extractive institutions

Sajith Premadasa or SP based his campaign on the wrong doings of the government in the recent past. But since he had been in a political party which had been in power for most of the period in the post-independence era, he could not come out clean from the charge of the extractive institutions that are supposed to have ruined the country. AKD did not have this weakness since he had not been in power, except for a brief period in early 2000s and his party had only 3 seats in Parliament. Thus, getting only 3% of the votes in the 2020 general election was a blessing for him.

A different type of a Parliamentary election

AKD is in power and seeks to get the majority power in Parliament in the general election fixed for 14 November 2024. SP is planning to get the majority in Parliament and promises that if elected to power, he will collaborate with AKD to deliver prosperity to people. RW is not contesting the elections but those who had supported him at the Presidential election are planning to form a strong opposition in Parliament. Delivering a special statement for the first time after his electoral defeat, he appealed to the voters to vote for the candidates who were with him when the economic reform program was introduced6. What he has forgotten is that voters in general have already branded them as extractive and the cause for the current economic hardships.

Avoidance of fostering extractive institutions

In my view, AKD, RW, and SP should learn one lesson from the Nobel Laureates. That is, they should not harbour extractive institutions in the country generally and among their rank and file more specifically. This message was delivered by AKD to candidates from his alliance when he addressed them: he said that the people will give his party the power to govern the country but those who are elected should form themselves to be of required quality meaning that they should not be extractive either as a group or as individuals7. This is a promising start, but he should ensure that what he preached to those candidates will be strictly followed. This is because of a general weakness which Acemoglu and Robinson had highlighted in their 2019 book, The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty, as the Gilgamesh Problem8.

|

Gilgamesh problem: saving people from saviours

Gilgamesh was the ruler of Uruk in ancient Sumaria in the 3rd millennium BCE. According to the epic recorded in clay tablets, he was a remarkable ruler with foresight and wisdom. He is said to have created a city flourishing with commerce and provided excellent public services for the people living there. But like any ruler with absolute powers, he thought that the city as well as the people therein belonged to him. He enlisted the young males for his war campaigns and young girls for his carnal pleasures. When people could not bear with this tyranny anymore, they are said to have appealed to the heavenly God Anu for redress. Anu created a double of Gilgamesh called Enkidu and sent him to Uruk to fight with Gilgamesh and protect the people from the latter’s tyrannical acts.

This was similar to the ‘checks and balances’ that we find in modern democratic constitutions. Enkidu did his job well by checking Gilgamesh whenever he tried to exceed his authority. But after some time, Enkidu found that if he teamed with Gilgamesh, he could also benefit from those evil works. It was a ‘win-win situation’ for both and they willingly agreed to work together. Now people in Uruk had a new problem, tyranny by Gilgamesh and his corrupt double, Enkidu. This problem, known as the Gilgamesh problem, is a common issue always faced by people and in all societies. It is concerned with how to save oneself from the saviours.

Learning lessons from Nobel Laureates

So, what are the lessons which AKD, SP, and RW should learn from the Nobel Laureates in economics in 2024? A lot. First, they should not be extractive in their values or behaviours as persons. Second, they should put a stop to extractive institutions being fostered in society. Third, they should observe the rule of law and not the rule of men to the letter. Fourth, they should ensure that the property rights are preserved via state as well as judicial action. Fifth, they should by word and deed should eliminate from the minds of people that the new era to be developed will not follow the past malpractices. Sixth, those who have done wrongs in the past should be brought to justice promptly. Seventh, they should put a stop to the ‘K’ type growth model in which the rich become richer, and the poor become poorer. Eighth, they should not allow the Gilgamesh Problem to rule over society.

Possibility of RW’s appeal going to deaf years and warning to AKD and SP

The most important learning lesson for RW will be that his appeal to voters that experienced people who had supported him to bring order to economy may have a high probability of going into deaf ears because, as the electorate has already demonstrated at the Presidential election, he and his supporters have been branded as extractive and potential Gilgamesh replicators if elected to power. This is also a warning to both AKD and SP to avoid this negative trait building in them as well as among their rank and file at all costs.

Footnotes:

1https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/colonial-origins-of-comparative-development.pdf

2North, Douglas, 1990, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

3Ibid p 4.

4Acemoglu, Daron, et al, 2005, Institutions as Fundamental Cause of Long-run Growth reproduced in MIT Economics (available at: https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/institutions-as-the-fundamental-cause-of-long-run-.pdf)

5Ibid p 389

6https://youtu.be/h9iWZoopONM?si=qIab1-Q0aw47AoOL

7https://youtu.be/hP0rrvy6UnI?si=vgDerB99PGH_yCs1

8Acemoglu, Daron and Robinson, James A, 2019, The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty, Penguin, New York, p xiii-xv

(The writer, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected].)