Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 18 March 2021 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

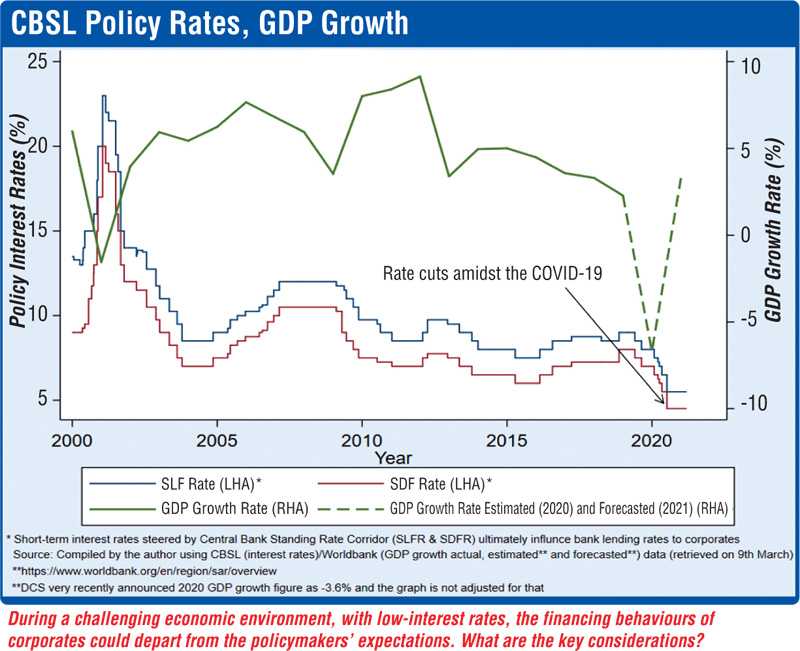

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka recently reaffirmed its commitment to maintaining a low-interest-rate environment at a policy meeting held earlier in March

With the last year’s deep dive into monetary easing amidst the COVID-19 initiated economic slowdown, Sri Lanka is still experiencing an environment of some of the country’s lowest interest rates in recent history.

With the last year’s deep dive into monetary easing amidst the COVID-19 initiated economic slowdown, Sri Lanka is still experiencing an environment of some of the country’s lowest interest rates in recent history.

A more recent development is that the Central Bank of Sri Lanka reaffirmed its commitment to maintaining a low-interest-rate environment at a policy meeting held earlier in March. Lower policy interest rates theoretically translate into lower borrowing costs and boost the credit flow towards firms. Hence, it is expected to create a feedback loop of growth that boosts economic activities by encouraging borrowing and investing.

However, it is also possible that the outcomes of these measures would deviate from the expectations, with unproductive effects on the economy. This article views this paradigm from the perspective of firm financing, an essential integrant in the recovery process. By weighing risks and potential benefits, it will discuss how to guide developments on a productive trajectory.

What does an economic slowdown mean with respect to firm financing?

In general, an economic slowdown slumps consumer spending. Fear and uncertainty begin to grip the consumer market, and lenders tend to pull back their money and become more selective with their lending criteria. Firms, those who depend on external financing to finance ongoing operations, get caught between both declining sales and tightening credit conditions.

The idea of monetary easing during an economic slowdown is to lower borrowing costs and increase the money supply; as the monetary authorities open the monetary floodgates, this financial pressure on firms is expected to decline. However, how long this should last and at what level it is appropriate is debatable.

Nevertheless, such measures expect firms to maintain their operations and, during the economic recovery cycle, permit them to invest in new projects and machinery; therefore, they catalyse the overall economy. Lower policy interest rates affect the borrowing costs of two main types of companies; public and private.

However, comparing public and private firms, the former has two options for raising capital: issuing new stock to the public and borrowing funds from lenders. By contrast, private firms have to depend on existing shareholders and borrowings. These corporate borrowings are measured through leverage; in some contexts, this is also called financial “gearing”.

Debt-to-Asset Ratio and Debt-to-Equity Ratio are main measures of leverage; as the names imply, these ratios measure a firm’s borrowings relative to their equity or asset base. A higher value indicates that a firm has a higher reliance on debt compared to its equity or asset base.

Firm financing over the business cycle

In general, firm financing studies imply that a firm’s total financing is procyclical either through debt or equity. Procyclicality (opposite: countercyclicality) means that they are either positively or negatively correlated with cyclical economic fluctuations and therefore react to economic variations. This is in line with the idea that firms reduce investments during economic downturns and accelerate investments once they see the light at the end of the tunnel, thereby optimising their debt-equity choice accordingly.

Although equity is one option for public firms, bank credit as the monetary transmission mechanism plays a crucial role in firm financing during economic downturns to support these firms. For example, discussions of former Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke (with Mark Gertler) support this idea [1]. A recent study by scholars from Stanford University and the University of Minnesota explains how small and large firms finance through debt and equity in the different phases of the business cycle [2].

According to the study, firm size is a key consideration for firm financing over the business cycle. Two considerations distinguish small and large firms: funding needs and funding capacity. Small, growing firms are firms with high funding needs but often constrained by their debt capacity. By comparison, large firms are particularly well established. They do not have strong investing requirements as small firms, but they also have a higher debt capacity.

Regardless of the business cycle stage, large firms find debt financing attractive, as economic downturns will have less of a detrimental effect on large firms’ credit quality than smaller firms. This implies that large firms also become attractive for lending institutions during economic down cycles as they are well established and less risky. In contrast, small growing firms become riskier for those institutions to lend to. Therefore, economic downcycles can increase the disparity between lending rates that lenders offer to large and small firms.

Overall, small and large firms’ drift apart in the lending markets during the economic downcycles is against the policymakers’ expectations. Through policy measures such as low-interest rates, policymakers expect growing firms to invest more and help the economy recover fast.

When it comes to debt instruments, firms have two options for debt financing, i.e. issuance of corporate bonds or borrowing through the banking system. However, due to the country’s less-developed corporate bond market, Sri Lankan firms rely more heavily on the banking channel for debt financing. This in turn can act as a headwind towards economic recovery, as had there been liquid and deep corporate bond market options available, the firm financing process would have been more effective, subject of course, to the risks attached to corporate bonds.

Improving the corporate bond market has the effect of somewhat reducing the pressure on the banking system. It provides an alternative risk measure for banks and prevents the banking system from being saturated by large firms. It also provides the central bank with an additional tool; the monetary authority can directly purchase corporate bonds to backstop corporations; this is a strategy adopted in most developed economies. If this is done with proper risk assessment, it provides confidence to those firms and the economy.

Global trends

In line with the theoretical framework discussed above, a recent article from Global Finance shows the low-interest rates does not necessarily mean funds are accessible to all the firms[3]. As banks started to tight lending standards with the rising expectations that the COVID initiated tension, corporates also started firming up their balance sheets and strengthening their market position to face this battle.

As the article shows, this created a wave of worldwide Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A), including in Asia, and the trend is expected to be stronger this year. Therefore, the article supports the idea that during the turbulent periods, it is possible to market to reach equilibrium lenders favour lager and strong institutions to mitigate risk, while large firms also grow up their institutions big and strong to become attractive, increasing the inequality between large and small borrowers.

Altogether, by considering theory and recent evidence, it is clear that the mechanism by which lower interest rates propagating into the corporate sector is not as straightforward as it seems. Instead, it is an outcome of a complicated process wherein both lenders and borrowers act strategically.

Knock-on effects on the stock market, lending institutions and the macroeconomy

When considering economic developments, there is a higher tendency that lower borrowing costs would increase the overall leverage of the market. Corporate leverage is helpful for firms up until a certain point; after that, it works adversely on firms and the economy. Excessive corporate leverage affects stock market volatility as well as exerting pressure on lending institutions.

On one hand, a paper by University of Rochester Professor Schwert William mentions that corporate leverage affects stock market volatility [4]. On the other hand, studies support the idea that high corporate leverage could also be harmful to lending institutions.

For example, a study by Saibal Ghosh explored this in the context of India and found that high corporate leverage is a determinant for predicting banks’ non-performing loans [5]. When considering the impact of financial leverage on the macroeconomy, potential risks risk on the macroeconomic stability caused by high-level corporate debt should be taken with care.

However, it is important to note that an overregulated approach would offset its potential efficiency benefits. Instead, policy measures should constructively steer these new developments in a progressive direction.

Policy considerations

From the perspective of economic policy, the ongoing low-interest-rate environment is relatively new to Sri Lanka. Policymakers can deploy new tools and strengthen macroprudential measures, including active supervision and macroprudential oversight. It is also important to analyse highly leveraged and unsustainable borrowers separately with prudential tools as their knock-on effects could cause adverse consequences for the rest of the economy.

In addition to this, targeted stress tests at banks’ loan portfolios would be another way of identifying the impact. However, most are not regulatory, but measures that encourage equal access to funds during the recovery process. Also, policymakers can encourage and support improved corporate governance measures; therefore, firms themselves can better manage market dynamics by identifying risks and prospects.

To summarise, this article discussed the ongoing challenging economic environment with the low-interest-rates environment and its means to firm financing and other economic considerations. Low-interest rates and lower borrowing costs may help firms fund their investments cheaply and help the economic revival process. However, it must be coupled with strong supporting mechanisms to mitigate adverse effects and guide measures along a productive trajectory.

(The writer is a PhD candidate attached to the Monash University - Australia. He pursued his graduate studies in Finance/Economics from the University of California, Berkeley, USA and the University of New Mexico, USA. He previously worked at institutions such as the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and BNP Paribas New York. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the writer. The writer could be reached via [email protected])

References:

[1] https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.9.4.27

[2] https://academic.oup.com/rfs/article/32/4/1235/5087739

[3] https://www.gfmag.com/magazine/february-2021/global-shakeout

[4] http://schwert.ssb.rochester.edu/faj90.pdf

[4] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13504850500378064