Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Wednesday, 19 July 2023 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A combination of falling GDP growth and rising inflation proves that Sri Lankan economy is under stagflation

A portmanteau formed from “stagnation” and “inflation”, stagflation is an economic hair-raiser. Though it doesn’t happen often, we should know what it is and what effects it can have. Specially its effects onto the stock market.

A portmanteau formed from “stagnation” and “inflation”, stagflation is an economic hair-raiser. Though it doesn’t happen often, we should know what it is and what effects it can have. Specially its effects onto the stock market.

“Stagflation” is a combination of high inflation and economic stagnation. Inflation drives prices up but purchasing power down resulting in lower corporate profits, increase in unemployment impeding growth in the stock market.

If the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI), the benchmark measurement of the local inflation, is rising that gives an indication that there is inflation in the Sri Lankan economy. Contemporarily if the q/q GDP growth is negative, there is stagflation in the Sri Lankan economy; the worse nightmare for the capital markets.

To avoid stagflation, governments adopt economic, monetary and fiscal policies; but they don’t always go hand in hand. There is no sure-fire way to get the economy back on track. Governments must strike a balance between lowering interest rates, increasing public spending and other ways to stimulate economic growth. However, this can actually raise inflation and increase the tax burden. So tightening monetary policy and other measures can also help put the brakes on. This surely is a tall order for the Sri Lankan Government at the present moment while attempting to salvage the country from a public debt crisis.

The GDP growth for the past 4 quarters of Sri Lanka according to the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) is as follows.

22 2nd Quarter -7.4

22 3rd Quarter -11.5

22 4th Quarter -12.5

23 1st Quarter -11.5

What is a recession

and is Sri Lankan economy in recession?

A common rule of thumb is that two consecutive quarters of negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth mean recession. Looking at the CBSL GDP growth figures above you now understand that the Sri Lankan economy is in in recession since 1st Quarter of 2022.

In the mission to determine if Sri Lanka is under stagflation we need to closely look at two contributing factors. That is the Q/Q GDP Growth and Inflation. If the Sri Lankan inflation is rising and GDP growth is declining then Sri Lankan economy is in stagflation. Looking at the GDP growth figures above it is very clear that the Sri Lankan GDP growth is in negative territory. Now let’s look at the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI) figures according to CBSL.

2023

January 54.20

February 50.60

March 50.30

April 35.30

May 25.20

2022

August 64.30

September 69.80

October 66.00

November 61.00

December 57.20

Except for the month of April and May 2023 you can notice a steady growth in Sri Lankan Inflation looking at the numbers of the CCPI above. A combination of falling GDP growth and rising inflation proves that Sri Lankan economy is under stagflation.

To better understand stagflation let’s look at what inflation and what cause it and what measures are taken by the policymakers to mitigate it when required.

Inflation is an increase in the prices of goods and services. The most well-known indicator of inflation in Sri Lanka is the Colombo Consumer Price Index (CCPI), which measures the percentage change in the price of a fixed basket of goods and services consumed by Sri Lankan households. The CPI is the measure of inflation used by the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL).

Causes of inflation

The main causes of inflation can be grouped into three broad categories:

As their names suggest, ‘demand-pulled inflation’ is caused by developments on the demand side of the economy, while ‘cost-pushed inflation’ is caused by the effect of higher input costs on the supply side of the economy. Inflation can also result from ‘inflation expectations’ – that is, what households and businesses think will happen to prices in the future can influence actual prices in the future. These different causes of inflation are considered by the CBSL when it analyses and forecasts inflation.

Demand-pulled inflation

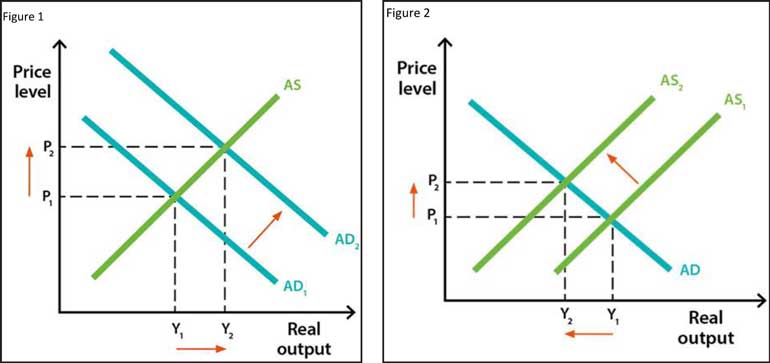

Demand-pulled inflation arises when the total demand for goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate demand’ AD) increases to exceed the supply of goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate supply’ AS) that can be sustainably produced. The excess demand puts upward pressure on prices across a broad range of goods and services and ultimately leads to an increase in inflation – that is, it ‘pulls’ inflation higher.

Demand-pulled inflation arises when the total demand for goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate demand’ AD) increases to exceed the supply of goods and services (i.e. ‘aggregate supply’ AS) that can be sustainably produced. The excess demand puts upward pressure on prices across a broad range of goods and services and ultimately leads to an increase in inflation – that is, it ‘pulls’ inflation higher.

Aggregate demand might increase because there is an increase in spending by consumers, businesses or government, or an increase in net exports. As a result, demand for goods and services will increase relative to their supply, providing scope for firms to increase prices (and their margins – which is their mark-up on costs). At the same time, firms will seek to employ more workers to meet this extra demand. With increased demand for labour, firms may have to offer higher wages to attract new staff and retain their existing employees. Firms may also increase the prices of their goods and services to cover their higher labour costs. More jobs and higher wages increase household incomes and lead to a rise in consumer spending, further increasing aggregate demand and the scope for firms to increase the prices of their goods and services. When this happens across a large number of businesses and sectors, this leads to an increase in inflation.

Demand pulled inflation generating due to growth, which is good Inflation for the economy. Higher household income increases the disposable income of the household thus increasing purchasing power resulting in higher prices. The policymakers use interest rate as a dynamic tool to control inflation propelled from the demand side. If the CBSL’s Monitory Policy Committee feels that the demand pulled inflation needs to be tamed they may decide to increase policy rates making saving instead of spending more attractive and borrowing and spending less attractive thus resulting in a slowdown in demand creating speed humps for inflation.

The opposite will happen when aggregate demand decreases; firms facing lower demand will either pause hiring or make staff redundant which means that fewer staff are required. This puts upward pressure on the unemployment rate. More workers searching for jobs means that firms can offer lower wages, putting downward pressure on household incomes, consumer spending and the prices of their goods and services. As a result, inflation will decrease.

The supply of goods and services that can be sustainably produced is also known as the economy’s potential output or full capacity. At this level of output, factors of production, such as labour and capital (which includes the machines and equipment firms use to produce their goods and services) are being used as intensively as possible without putting upward pressure on inflation. When aggregate demand exceeds the economy’s potential output, this will put upward pressure on prices. When aggregate demand is below potential output, this will put downward pressure on prices.

In United States Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) of the Federal Reserve Bank (FED) follows a few more Economic Indicators other than the Consumer Price Index (CPI) being an industrialised economy with an annual GDP in excess of $ 23 trillion. In addition to CPI the Fed looks at Producer Price Index (PPI). The PPI measures the average change over time in the prices domestic producers receive for their output. It is a measure of inflation at the wholesale level that is compiled from thousands of indexes measuring producer prices by industry and product category. The PPI gives an indication of the Price pressures which are in the pipeline (at the production and wholesale level) which would hit the shelves of the grocery stores soon. In most occasions PPI acts as a precursor to the shifts of the CPI. This measurement is calculated by the Department of Census and Statistics in Sri Lanka as well but not given much importance by the media and traders.

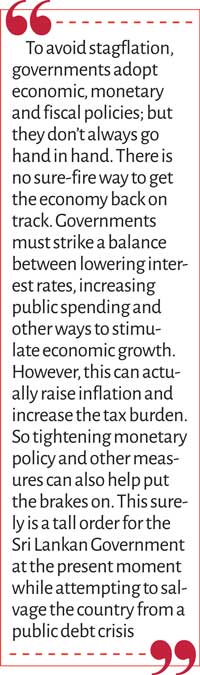

Cost-pushed inflation

Cost-pushed inflation occurs when the total supply of goods and services in the economy which can be produced (aggregate supply) falls. A fall in aggregate supply is often caused by an increase in the cost of production. If aggregate supply falls but aggregate demand remains unchanged, there is upward pressure on prices and inflation – that is, inflation is ‘pushed’ higher.

An increase in the price of domestic or imported inputs (such as oil or raw materials) pushes up production costs. As firms are faced with higher costs of producing each unit of output they tend to produce a lower level of output and raise the prices of their goods and services. This can have flow-on effects by pushing up the prices of other goods and services. For example, an increase in the price of oil, which is a major input in many sectors of the economy, will initially lead to higher Gasoline and Diesel prices. However, higher Fuel prices will also make it more expensive to transport goods from one location to another which, in turn, will result in increased prices for items like groceries.

Cost-pushed inflation can also arise due to supply disruptions in specific industries – for example, due to unusual weather or natural disasters. Periodically, there are major cyclones and floods that damage large volumes of agricultural produce and result in significant increases in the prices.

The war between Ukraine and Russia effected in a major supply disruption of many Grains. Naturally, Russia’s invasion has affected sowing and harvesting in Ukraine. It has also affected availability and production in the rest of the world. In early March 2022, prices were reported to have increased by considerable margins for wheat, corn, and soybean. Prices of fertiliser have risen too. As a result of increase in price of corn, which is a major component of poultry feed, created a rice of all poultry related products across the world. This effected Sri Lankan poultry farmers significantly and it impacted the CCPI considerably. This impacted the Sri Lankan society to an extent which turned it in to a political issue. The war in Europe effected supply disruptions of sunflower seed production resulting in a major price increase in sunflower oil. This had a domino effect on prices of all edible oil prices globally including in Sri Lanka.

Imported inflation

and the exchange rate

Exchange rate movements can also affect prices and influence inflation outcomes. A decrease in the value of the domestic currency − that is, a depreciation − will increase inflation in two ways. First, the prices of goods and services produced overseas rise relative to those produced domestically. Consequently, consumers pay more to buy the same imported products and firms that rely on imported raw materials in their production processes pay more to buy these inputs. The price increases of imported goods and services contribute directly to inflation through the cost-push channel.

The volatilities in LKR (Lankan Rupee)/ USD (United States Dollar) exchange rate had a massive impact to the Sri Lankan Economy as a whole as Sri Lanka imports many consumer goods and most raw materials. A depreciation of the currency stimulates aggregate demand. This occurs because exports become relatively cheaper for foreigners to buy, leading to an increase in demand for exports and higher aggregate demand. At the same time, domestic consumers and firms reduce their consumption of relatively more expensive imports and shift their purchases towards domestically produced goods and services, again leading to an increase in aggregate demand. This increase in aggregate demand puts pressure on domestic production capacity, and increases the scope for domestic firms to raise their prices. These price increases contribute indirectly to inflation through the demand-pull channel.

In terms of imported inflation, the exchange rate has a greater influence on inflation through its effect on the prices of goods and services that are exported and imported (known as tradable goods and services), while prices of non-tradable goods and services depend more on domestic developments.

Inflation expectations

Inflation expectations are the beliefs that households and firms have about future price increases. They are important because expectations about future price increases can affect current economic decisions that can influence actual inflation outcomes. For example, if firms expect future inflation to be higher and act on those beliefs, they may raise the prices of their goods and services at a faster rate. Similarly, if workers expect future inflation to be higher, they may demand higher wages to make up for the expected loss of their purchasing power. These behaviours, sometimes called ‘inflation psychology’, can contribute to a higher rate of actual inflation so that expectations about inflation become self-fulfilling.

Given that inflation expectations can influence actual price and wage setting, the extent to which inflation expectations are ‘anchored’ has implications for future inflation outcomes. For example, if households’ and firms’ expect that inflation will return to the central bank’s inflation target at some point in the future, regardless of what current inflation is, we describe their expectations as being ‘anchored’ to the inflation target. When expectations are anchored, a period of higher inflation – perhaps resulting from a cost‑push event – will not cause households and firms to change their behaviour and, as a result, inflation is likely to eventually return to its target. But if the inflation psychology of households and firms shifts and inflation expectations move away from the central bank’s inflation target (i.e. they become ‘unanchored’), a period of higher inflation will become persistent because households and firms will expect inflation to be higher in the future and adjust their behaviour accordingly. Consequently, it is much easier for a central bank to manage inflation if inflation expectations are anchored rather than unanchored.

If a supply shock is sufficiently large or persistent, it not only causes cost‑push inflation, but can noticeably reduce both the current and potential level of output in an economy. In this case, there can be the unusual combination of a period of ‘stagnation’ as output declines at the same time that prices are rising. This combination of stagnant growth – with high or rising unemployment – and high inflation is referred to as stagflation. Stagflation can become entrenched when inflation expectations are not well anchored. This is what is prevailing in Sri Lankan economy. The increase of interest rates is done to curb Demand Pulled inflation.

If the rates are increased for any other reason besides mitigating demand pulled inflation (example – to make purchasing of Government issued bonds more attractive) then that would have adverse effects on output, unemployment, spending, and stock market leading to stagflation. Looking at demand, employment global supply chain disruptions volatile global energy markets, exchange rate risks, non-availability of a futures exchange for hedging such risks suggests that the Colombo Stock Exchange is still deep inside the woods. It would be highly recommended to sell on upticks and be keep your powder dry (Stay alert, be careful, be liquid ready for action.)