Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Thursday, 15 August 2019 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

People will always believe what they want to believe, how they want to believe it, when they want to believe it. The events of Easter Sunday 2019 (Sunday 21 April 2019) triggered a process in Sri Lanka which has exposed the entire Sri Lankan Muslim population to this concept in a very negative sense. Questions which were discussed previously in the rarefied atmosphere of academic conferences have entered the mainstream of public consciousness. Islam or some variant of it – whether distorted, perverted, corrupted or hijacked by extremist – has become a force to reckon with, or at least has a label attached to a phenomenon with menacing personalities.

Islam is a religion of peace: the word, a verbal noun meaning submission (to God), is etymologically related to the word salaam, meaning peace. So, how is it that a religion of peace practiced by traditional Sri Lankan Muslims for thousands of years in harmony and co-existence with Buddhists, Hindus and Christians became an ideology for hatred and animosity towards other communities? Academic work done by Dr. M.A.M. Shukri (1986) and Lorna Dewaraja (1994) seminally document this fact.

In an era of sound-bites and newspaper agendas driven by tabloid headlines, the lives of peace-loving majorities are inevitably obscured by attention seeking acts of minorities. The news media acts like a distorting mirror, exaggerating the militancy of a few while minimising the quietism or indifference of the many. This outstanding feature of modern society has been successfully exploited by extremists on all sides (minority, majority and all in between!) to further their individual identity driven agendas at the expense of the common Sri Lankan national identity. The principle drivers of this vicious cycle are the politicians and religious clergy on all sides.

It is in this context that the current revived interest in Islam and Muslims should be viewed and used as an opportunity to enlighten the Sri Lankan public on the basics of Islam and Muslims.

Defining Islam and for that matter any faith-based ideology/religion is far from simple. This must be reiterated and remembered throughout this brief monograph. (Faith is under no obligation to make sense to anyone other than those who profess in it).

If we are (truly ever) going to evolve as a ‘Sri Lankan Nation’ in a ‘democratic’ (as opposed to an ethnocratic) backdrop, we must firstly understand, appreciate and respect each other’s religious, cultural and social identity; which ought to be contributing towards a truly Sri Lankan identity. If not, we will end up promoting Sinhalese/Buddhist nations, Sinhalese/Christian nations, Tamil/Hindu nations and Tamil/Christian nations. The term ‘Muslim’ in the Sri Lankan context which denotes a religious denomination as opposed to an ethno-cultural one has so far precluded the Sri Lankan Muslims from thinking terms of Islamic/Muslim nation.

The intention of this monograph is to contribute towards the understanding of the true Sri Lankan Identity from the global and local perspective of the religion Islam and the Muslim identity.

In understanding Islam there are three basic concepts to be aware of and addressed;

1. The concept of Islam as a faith

2. The concept of Islam as a political ideology

3. The concept of Islam as an individual/group identity

1. The concept of Islam as a faith

Islam is an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion. Historically it is believed to have originated in the early 7th century CE in Mecca, in present day Saudi Arabia, and was founded by Muhammad (570-632 CE). Islamic scriptures claim Islam to be the complete and universal version of a primordial faith that was revealed many times before to prophets including Adam, Abraham, Moses and Jesus. The primary sources of Islam are derived from,

1. The Quran – In its original Arabic form the verbatim words of God (Allah)

2. The Sunna and Haddith – Teachings and normative examples from the life of Prophet Mohammed (Peace Be Upon Him)

Islam like other Abrahamic religions teaches a final judgement with the righteous rewarded with heaven and the unrighteous punished in hell. It also strongly brings forth the concept of divine will – everything, good and bad is believed to have been decreed. Its religious concepts and practices include the five pillars of Islam which are obligatory acts of worship and following the Islamic law (Sharia) which virtually touches every aspect of individual and collective life.

1. The profession of faith – Sahada (There is no god but God; Muhammad is the messenger of God)

2. Daily prayers – Salat

3. Alms-giving – Zakat

4. Fasting during the month Ramadan – Saum

5. Pilgrimage to Mecca – Haj

Upon the death of the founder of Islam on 8 June 632 CE, he was succeeded by four of his companions who became the rulers of the then Islamic ‘state’ and religious leaders of the new religion of Islam (Abu Bakar – 632 to 634 CE, Umar ibn Khattab – 634 to 644 CE, Uthman ibn Afan 644 to 656 CE and Ali ibn Abu Talib 656 to661 CE). On the death of the last Calipha the religious differences, which had begun to emerge during the period immediately following the death of the Prophet became more formalised and led to the division of Islam as a religion in to several branches.

These divisions were primarily on the grounds of theological and political interpretations of Islam. The main two branches of Islam are the Sunnis (comprising of 75-90% global Muslims today) and the Shias (comprising 10-20% of global Muslims today). The first four caliphs were followed by dynastic caliphates and eventually succeeded by the establishment of the Ottoman Empire.

Each major branch of Islam has several sects within them (once again sub divided on their methodology of religious traditions and practice based on interpretation of Islamic law – the Sharia). A few examples of these sub sects are;

1. Within the Sunni branch of Islam (also known as Ahl as-Sunnah) – Shafie, Hanafi, Hanbali and Maliki. The vast majority of Sri Lankan Muslims belong and practice this branch of Islam.

2. Within the Shia branch of Islam – Ismaili, Ja’fari, Zaidi. A small minority of Sri Lankan Muslims belong to this branch of Islam and most of them belong to the Sub sect Ismailis who are once again sub divided in to the Musta’il sub sect and the Tayyabi sub sub sect to whom the Dawoodi Bohras belong. (Please note that there are many other sub sects of the Bohras in other parts of the world)

3. Other denomination – Ahamadeiya, Bektashi Alevism, Ibadi, Mahadavia, Quranists (main stream Muslims do not consider followers of these denominations to be ‘Muslims’)

Note 1 – Wahabism – is a sub sect of the Sunni branch of Islam which came in to existence in the 18th century led by Muhammad ibn Andbd al Wahab in the geographical region of present-day Saudi Arabia. Originally shaped by Hanbalism, many modern followers departed from any of the established four schools of Sunni Law. The salient feature of this sub sects is its particularly strict adherence to the Quran and Hadith

Note 2 – Sufism (aka – Tasawwuf) – is a mystical-ascetic ‘approach’ to Islam that seeks to find a direct personal experience with God. It is not a sect of Islam and its adherents belong to various Islamic denominations.

Islam unlike the other Abrahamic religions does not have sacerdotal priesthood (no priests who act as mediators between God and the people)

1.1 Sharia (Also known as Shariah or Shari’a)

Literally meaning ‘the way’, it is an Islamic religious law that governs not only religious rituals but also aspects of day-to-day life in Islam. There is extreme variation in how Sharia is interpreted and implemented among Muslim societies (traditionalist and reformist groups) today.

The aim of Sharia is to preserve the five essentials of human well-being – religion, life, intellect, offspring and property.

The Sharia has four sources. The two primary sources are the Quran and the Haddith (teachings and normative examples form the life of Prophet Mohammed). Islamic jurisprudence also recognises Qiyas (analytical reasoning) and Ijma (juridical consensus) as the other two sources. Traditional jurisprudence distinguishes two principal branches of law – Rituals (ibadat) and Social Relations (mu’amlat). The rulings based on Sharia are concerned with ethical standards as much as it is with legal norms and are categorised in to five categories – Mandatory (Fard or Wajib), Recommended (mandub or mustahabb), Neutral (mubah), Reprehensible (makruh) and Forbidden (Haram). It is a sin or crime to perform a forbidden action or not to perform a mandatory action. Avoiding reprehensible acts and performing recommended acts is held to be subject of reward in the afterlife, while neutral actional entail no judgement from God.

The mechanism of administering and implementing the Sharia (particularly in localities where Muslims live as minorities) is by private religious ‘scholars’ (who usually hold other jobs), largely through legal opinion (fatwas) issued by qualified jurists (muftis).

1.2 Halal (in relation to edible items – food)

The Halal in Arabic means lawful or permitted. The opposite to it is Haram – unlawful or prohibited. These two terms are universal terms that apply to all facets of life.

Since food is an important part of daily life, food laws carry special significance.

In reference to food, Halal is a dietary standard as prescribed in the Quran and Hadith. The term Halal is in relation to food products, meat products, cosmetics, personal care products, pharmaceuticals, food ingredients and food contact material. At the very basic level Halal food are those that are;

1. Free from any component that Muslims are prohibited from consuming according to Islamic law (Sharia)

2. Processed, made, produced, manufactured and/or stored using utensils, equipment and/or machinery that have been cleansed according to Islamic law.

1.3 Jihad

Jihad is an Arabic word which means striving or struggling, especially with a praiseworthy aim.

In an Islamic context, it can refer to almost any effort to make personal and social life conform with God’s guidance, such as struggle against one’s evil inclinations or efforts towards the moral benefit of the Muslim community (Ummah).

Jihad is classified in to Inner (‘greater’) jihad, which involves a struggle against one’s own basic impulses and External (‘lesser’) jihad, which is further subdivided in to jihad of the pen/tongue (debate and persuasion) and jihad of the sword. Most Western writers consider external jihad to have primacy over inner jihad in Islamic tradition, while much of contemporary Muslim opinion favours the opposite view. This possibly is the basis that jihad is most readily and commonly associated with the act of war.

In classical Islamic law, the term commonly referred to armed struggles against ‘non-believers’, while modernist Islamic scholars generally equate armed jihad with self-defensive warfare. In the modern era, the notion of jihad has lost its jurisprudential relevance and instead given rise to an ideological and political discourse. (While modernist Islamic scholars have emphasised defensive and non-military aspects of jihad, some Islamists have advanced aggressive interpretations that go well beyond the classical theory).

2. The concept of Islam as a political ideology

Ideologies are powerful systems of widely shared ideas and patterned beliefs that are accepted as truth by a significant group in society. It serves as a political map that offer people a coherent picture of the world not only as it is, but also as it ought to be. In doing so, ideologies help organise the tremendous complexity of human experience into simple claims that serve as a guide and compass for social and political action. These claims are employed to legitimise certain political interests and to defend or challenge dominant power structures.

Seeking to imbue society with their preferred norms and values, the codifiers of these ideologies (usually politicians and members of the clergy) speak to their audience in a narrative that persuades, praises, condemns, distinguishes ‘truths’ from ‘falsehoods’ and separate the ‘good’ from the ‘bad’. Thus, ideology connects theory and practice by orienting and organising human action in accordance with generalised claims and codes of conduct.

Throughout history, Islamic rectitude has tended to be defined in relation to practice rather than doctrine. Muslims who dissented from the majority on issues of leadership or theology were usually tolerated provided their social behaviour conformed to generally accepted standards. It is enforcing behavioural conformity (orthopraxy) rather than doctrinal conformity (orthodoxy) that Muslim radicals or political activists look towards using Political Islam to drive and achieve their agendas.

The most visible and prominent example of orthopraxy in Sri Lanka is the enforcement (voluntary or otherwise) of an ‘Islamic Dress Code’ (as opposed to a traditional Sri Lankan Muslim dress code) by a fundamentalist driven Islamic clergy who’s patronage Sri Lankan Muslim based political parties and politicians of all hues seek.

Historically, Islamic societies have been governed by Islamic Law even when they are minorities. In societies where Muslims are a minority, they, while conforming to national laws have put in place institutional arrangements to follow an enforce Islamic Law to varying degrees either voluntarily or within accepted frameworks set up by state-led entities (as in Sri Lanka). This scenario, (where Muslims are in a minority) has always led to gaps between the theoretical formulations of Islamic jurists and the de facto exercise of their political power.

In the Sri Lankan context Muslim School System (under the Ministry of Education), the Madrassa Education System (currently outside the preview of state regulation), the Muslim Marriages and Divorce Act of 1951 (MMDA), the issuing of Halal Certificates are few among numerous examples of this gap between Islamic jurists and the exercise of their political power.

‘The Muslims of Sri Lanka had till very recently achieved complete political integration with majority community in the sense that the Muslims, had no Muslim political parties based on linguistic or religious issues, nominating their candidates for parliamentary seats through ‘national’ parties. Muslims are represented and have risen to pre-eminence in all the major political parties in the island. The situation changed recently as there has been an attempt to establish a separate Muslim political identity in Sri Lanka. The aspirations of a new generation of educated Muslims and the pressure of international currents of opinion were factors which contributed toward this claim. Another factor which heightened Muslim consciousness was the Sinhala-Tamil conflict that plagued the island’. (Lorna Dewaraja, The Muslim of Sri Lanka-One thousand years of ethnic harmony-900 to 1915).

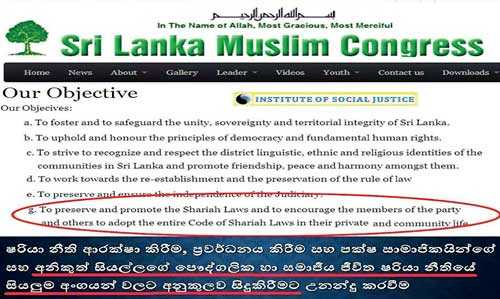

Please see the figure which demonstrates the use of Islamic Law (Sharia) as a political tool to gain the political support of Sri Lankan Muslims. It is this type of segmented ethnoreligious based politics prevalent in Sri Lanka due to the proportional representation system of the electoral process which empowers and sustains religious based political parties. As of today, as per the Sri Lankan Constitution a political entity needs a mere 5% of the vote in a defined geographical area to obtain political representation in either local or national legislative Councils.

This figure of 5% was originally 12% but due to political manoeuvring it was brought down to the current level of 5%. This Constitutional clause allows minority parties (particularly regional based religious minority parties) to obtain parliamentary representation and influence national polices from narrow ethnoreligious driven political agendas. This undermines the need for minority communities to engage in politics through national parties as their chances of electoral success are diminished by the existence of religious based parties.

To put the above in to democratic context (or is it ethnocratic context?), analysis of past national level voter patterns indicates that approximately 300,000 to 350,000 individual votes received by regional based religious – Muslim-political parties are a key deciding factor in formation of national governments. In other words, it is about 300-350,000 voters of regional based religious political parties who control the political destiny of Sri Lanka.

In the view of political Islam’s numerous critics, Muslims and non-Muslims, Islam as a religion should be distinguished from Islam as a political ideology. The greatest criticism of Islamic based political parties is that they actively aim to replace the sovereignty of the people with the sovereignty of God to further their own narrow political agendas.

2.1 Islamic globalism

Islamic globalism (the concept which operationalised the Easter Sunday 2019 carnage in Sri Lanka) is anchored in the core concepts of umma (Islamic community of believers) and jihad (unarmed and armed struggle against unbelief purely for the sake of God and his umma). Islamic globalists understand the umma as a single community of believers united by their belief in the one and only God. Expressing a religious-populist yearning for strong leaders who set things right by fighting alien invaders and corrupt Islamic elites, they claim to return power back to the ‘Muslim masses’ and restore the umma to its earlier glory.

In their view, the process of regeneration must start with small but dedicated vanguard of warriors willing to sacrifice their lives as martyrs to the holy cause of awakening people to their religious duty – not just in traditionally Islamic countries, but wherever members of the umma yearn for the establishment of God’s rule on earth.

With a third of the world’s Muslims living today as minorities in non-Islamic countries, Islamic globalism regards the restoration as no longer a local, national or even a regional event. Rather, it requires global efforts spearheaded by jihadists operating in various localities around the world.

This in summary was the political Islamic ideology which operationalised the Easter Sunday 2019 carnage in Sri Lanka.

The status quo with regards to the Islamic religious background and infrastructure which guided or misguided the zealots who carried out the Easter Sunday 2019 carnage in Sri Lanka is still very much active. The fundamentalist Islamic clergy organisation/s which gave birth to the various militant extremist Islamic terrorist movements through their Islamic ideological guidance still receives wide state and community patronage and support. If this scenario, through a deep understanding of political Islam is not dealt with it is only a matter of time before we in Sri Lanka will witness perhaps an even more catastrophic loss of life and property with much bigger backlash against the majority Muslims of Sri Lanka.

To be Continued tomorrow