Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Wednesday Feb 11, 2026

Friday, 27 November 2020 00:25 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

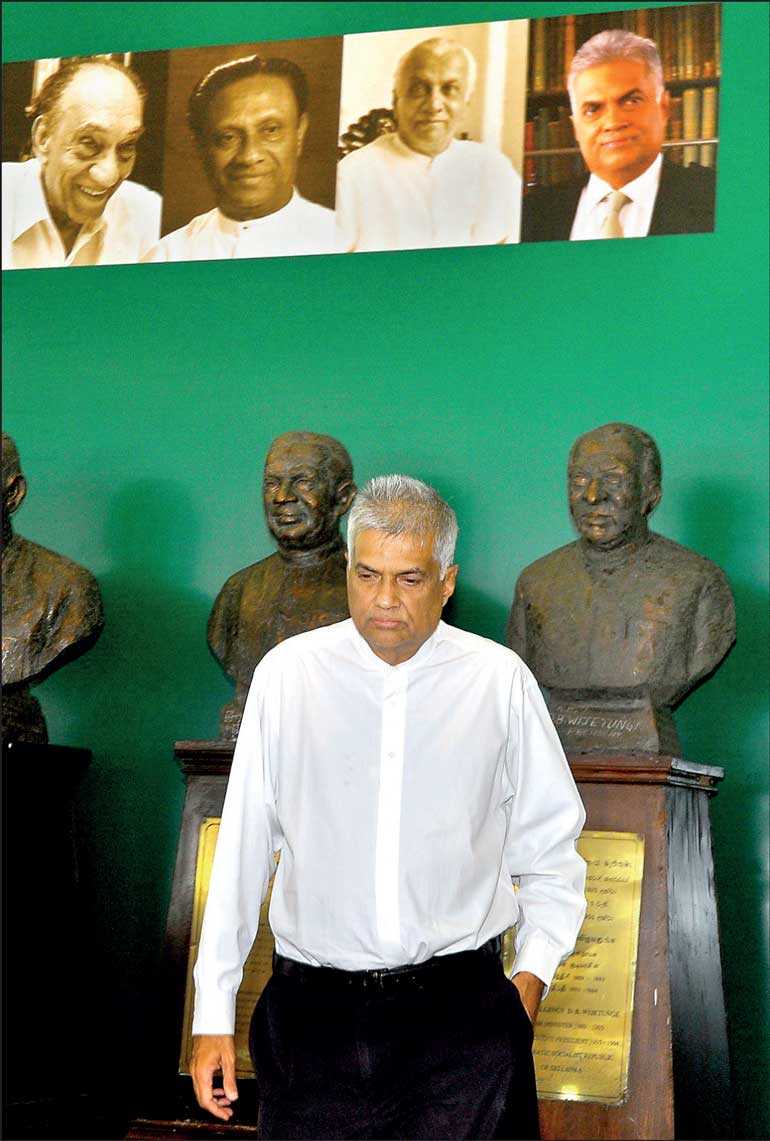

In politics, Ranil was known as an ace trickster. Yet, in the end, he was doomed politically as a result of being caught in a trap set by others against him – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

The process of the old stock of political leaders and their parties losing the recognition they have enjoyed so far can be described as an integral part of the historical process of ending the old era of the political history of Sri Lanka. The loss of recognition enjoyed by Ranil Wickremesinghe, the Leader of the UNP, and his party can be seen as an outcome of this historical process.

the UNP, and his party can be seen as an outcome of this historical process.

Even the Samagi Jana Balawegaya which has made a critical impact on the downfall of the UNP and its Leader Ranil Wickremesinghe has not been able to secure adequate Parliamentary representation to establish itself as a powerful alternative force. Perceived from this angle, it appears that in symbolic sense the political movement of the UNP has come to an end.

Nepotism and family bandism

The UNP is the second oldest party, next only to the Lanka Sama Samaja Party. The UNP was established in 1946 while the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) was founded in 1935. It has ruled the country alternately for almost half of the post-independence period, the remaining period being ruled by the SLFP. Under the circumstances, both parties, the UNP and the SLFP, are equally responsible for the defeats suffered and victories gained by the country. The UNP can be considered as the biggest party that Sri Lanka had.

It is mostly the Rajapaksa family being referred to when nepotism or family bandism in politics is talked about. Similarly, the UNP also can be described as a party founded and maintained by a strong family cartel closely linked by kinship. The strong and influential members of this family cartel can be considered as a close-knit family network which had become affluent through various commercial ventures including the arrack trade during the British rule and had achieved prestigious status in the society. So much so, in the early years of its rule the UNP was known as the ‘Uncle-Nephew Party’ because of the close blood ties between its major leaders.

Bandaranaike left the UNP as he believed that he would not stand a chance to be the leader of the party, no matter how qualified he was. Following the assassination of Bandaranaike, his widow took the reins of the SLFP and built it as a personal fiefdom of her family. During the 1977 General Election, the UNP sarcastically compared the Government of Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike to a family tree and a book was also published with cartoon-style illustrations in this connection.

Apparently the Rajapaksas might have learnt the importance attached to family bandism or nepotism from Senanayakes, Jayewardenes and Sirima Bandaranaike. Finally it was Rajapaksas who became veterans of it.

J.R. Jayewardene

J.R. Jayewardene was a leader who showed greater sensitivity for family bandism, though he claimed during the 1977 election that he had no prince or princess to be crowned. In preparing the potential queue of future leaders of the UNP in 1977, he did not forget to carve out a niche for Ranil Wickremesinghe, an important member of his family, and place him in an important slot in it.

President Jayewardene offered him the post of Deputy Foreign Minister in his Government of 1977 and then made him a Cabinet Minister in the very first Cabinet reshuffle. Perhaps, President Jayewardene might have expected that, on account of family ties, Ranil should succeed him as the leader of the party. Following the assassinations of President Ranasinghe Premadasa, Lalith Athulathmudali and Gamini Dissanayake, Ranil was able to sail into the leadership of the party without a major challenge. Both Jayewardene and Premadasa ruled the party the way the autocratic leaders control their teams. In doing so, the two leaders were able to maintain a Machiavellian atmosphere within the party which ensured maximum loyalty of the party members to the party leader.

Ranil’s limitations

But Ranil did not possess the Machiavellian toughness displayed by his two predecessors. A leader like Ranil should have achieved that stature by changing the feudal nature of the party and making it more democratic in functioning. Ranil had the necessary knowledge for that, but he did not take an interest in democratising the party and establishing himself as a democratic leader in the precincts of the party itself. Instead, he augmented the dictatorial nature of the Party Constitution and assumed the role of a dictatorial leader within the party while seeking to project the image of a democratic leader in the face of the country.

President Jayewardene strengthened the UNP. But at the same time he contributed to corrupting the party to the maximum. With the abolition of laws that governed the utilisation of party funds and election funds, the UNP has become a party that depends on black money. Not only the party but also the Parliament and the entire political system decayed into a state of rottenness with rampant corruption following the MPs being allowed to transact business with the government in violation of the law of the land and the accepted ethics of the world.

President Jayewardene let the plunder of public property become a regular feature of State rule. Corruption can be considered as one of the main factors that have largely contributed to destruction and the failure of Sri Lanka. If Ranil had a sincere desire to rescue Sri Lanka from corruption, first of all, he should have rescued his party from corruption. For whatever reason, Ranil did not have a genuine desire for it. As a result, Ranil lost the opportunity to implement a genuine reforms program for Sri Lanka despite him having the necessary knowledge for that. When he came to power in 2001, he was well aware that the Judiciary was rife with corruption. Despite having enough power to change the situation he did nothing effective except for standing aloof and leaving the problem to aggravate and fossilised.

Caught in a trap

In the modern sense, Sri Lanka cannot be considered a country that has produced mature political leaders. Ranil was an exception and can be considered as the most knowledgeable and experienced leader among contemporary politicians.

In politics, Ranil was known as an ace trickster. Yet, in the end, he was doomed politically as a result of being caught in a trap set by others against him. From the outset, I perceived the Yahapalana program as a tactical ploy launched by a third party using the name of Venerable Sobitha Thero also in it with cynical intentions of capturing power in a devious way by defeating not only Mahinda Rajapaksa but also Ranil Wickremesinghe as well. I have spoken and written about it in public at that time.

The idea of the common candidate had been used to substantiate the argument that Ranil lacked the strength to defeat a powerful leader of the calibre of Mahinda Rajapaksa. But in 2005, Ranil contested the Presidential Election with Mahinda and lost because of the election boycott imposed by Prabhakaran. If Ranil was not the most suitable candidate of the UNP, then a suitable contestant should have been found from within the party and not from outside. Arising of serious confusions is inevitable when an outsider is brought to power using the powerful vote base of the UNP. On the other hand, it is a great injustice done to the party. Moreover, there should have been a system in place to restrict the outsider, the common candidate if he tends to misuse the enormous power that he gains. But there was no such mechanism incorporated into the Yahapalana program. Even the reforms program presented with the Yahapalana formula can also be considered as a false program formulated ignoring the real reforms that the country needed.

I spoke to Ranil and expressed my views on the dangers of this program. At that time Maithripala Sirisena had not been chosen as the common candidate. I told him that the dream of a common candidate will be shattered if the UNP could field a candidate of its own for the Presidential Election and then the UNP will have a chance to contest it and initially there can be minor misunderstandings, but eventually all anti-Mahinda factions will support the UNP candidate. Ranil not only listened to my views but endorsed them.

Thereafter, I met Karu Jayasuriya, blamed him for being a party to the program of the common candidate and warned him about the dire consequences of it. Then I met with Ven. Sobitha Thera and talked about it. Mano Tittawella and Sumathipala Kariyawasam were also present in this discussion. I stated that if we want to defeat Mahinda Rajapaksa, it should be done formally as the informal attempts can have disastrous consequences.

Finally, Ranil agreed to the candidacy of Maithripala Sirisena because of the firm assurance given by Chandrika on his behalf. On account of Chandrika’s patronage Ranil believed that the anti-Ranil elements behind the Yahapalana program would not stand a chance to enter into a big deal with Maithripala. However, in the end Ranil became an inescapable prisoner of the Yahapalana trap.

If Ranil had contested the 2015 Presidential Election, probably he would have won it in a close contest. But I don’t believe that it would have made a big difference except for retarding the rapidity of the speed at which the country was moving towards destruction.

Conclusion

Not only the present rulers, but also the previous rulers are equally responsible for the disaster that the country is facing now. All the leaders involved in the Yahapalana regime knowingly or unknowingly have duped the reforms needs of Sri Lanka. It’s a different matter that the actual reforms needed for Sri Lanka have not been identified correctly and wisely. Yet, the sacrifice made to achieve even those reforms that they introduced has cost the lives of several thousands of people and the sweat and tears of many more who had been oppressed for their attempt to realise them.

Most of their reforms have been reversed the way a tender plant is uprooted with a tiny shovel. The rest, it is clear, has been implemented in a mighty hurry, and on shifting sand without a strong foundation. The Judiciary was in a state of extreme degeneration. The Yahapalana Government did not have a clear vision to rectify the situation, and it foolishly believed that the system of independent commissions would automatically clean up the Judiciary.

The Court’s decision on Ranil Wickremesinghe preventing him from being removed from the portfolio of the Prime Minister was viewed as a significant indicator that reflected the outstanding progress presumed to have been achieved by the Judiciary. However, this judgment was given not because the Judiciary in general has achieved great progress, but apparently because the Chief Justice who had reached the retirement age possessed a strong urge to mete out justice impartially. After this judgement, many things have happened in the Judiciary that should not have happened in a Court of Law. On this subject, sadly, Sri Lanka is now in a state of a deep abyss.