Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday, 10 April 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

This is a continuation of what I published earlier, titled ‘Thoughts on Economic Recovery and Return to Normalcy after COVID-19’ (Daily FT 7 April, http://www.ft.lk/columns/Thoughts-on-economic-recovery-

|

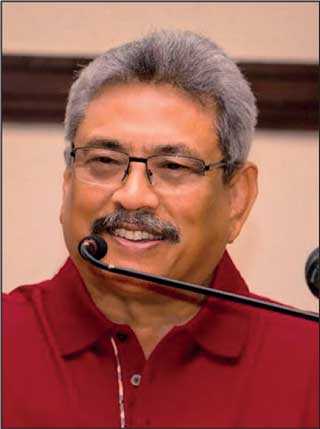

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa |

and-return-to-normalcy-after-COVID-19/4-698574).

The way President GR is handling the COVID-19 devastation, as an emergency situation and tackling it with military discipline, is commendable. Even other and more established democratic countries have assumed a wartime governing model and are implementing measures to combat the virus, which unavoidably has disrupted normal life in all its aspects and liberties taken for granted are called to be sacrificed. People understand the Government’s desperation and the need for desperate measures. In this situation the need for national unity and cooperation with authorities is pivotal. Period.

The only unwritten condition attached to this unity and cooperation is the understanding that once the emergency passes away, situation would return to previous status quo. People would expect to go back to their habitual ways of doing things. They may adopt certain changes to their lifestyle because of lessons learnt during the emergency, and authorities in turn would be expected to relax and remove the restrictions imposed temporarily.

It is the suspicion and fear of that expectation remaining unfulfilled and exceptions threatening to become normal that tend to make unity and cooperation problematic. This is particularly acute in  societies with different ethnic and religious compositions, and which experience discriminatory treatment in the hands of rulers and administrators. Sri Lanka falls into this category.

societies with different ethnic and religious compositions, and which experience discriminatory treatment in the hands of rulers and administrators. Sri Lanka falls into this category.

In the midst of the COVID-19 emergency, the issue of cremating or burying a dead body has raised concern among Muslims and provided an opportunity to few of their leaders to make political capital out of it. This is unfortunate.

Although I am not a Muslim theologian, my understanding of that faith and its history convince me that, in exceptional circumstances, such as when large numbers of people are threatened to be infected through burial, cremation may be allowed as the only option.

According to the Islamic faith, God can bring back the dead to life whether buried, cremated or even dissolved in chemicals, as happened to Jamal Kashoggi. Then why the fuss? The reason is the ethno-nationalist political atmosphere allowed to flourish in the country.

This is not the time to discuss this issue in detail, which I have done in a number of previous contributions to this journal. However, let me remind the readers of a recent controversy surrounding the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act during the Yahapalana regime.

Again, I have expressed my views on this Act before and don’t want to repeat them here. But, during the closing days of that regime, the maverick monk Ven. Athuraliye Rathana Thera, introduced a private Bill in Parliament and argued for the abolition of MMDA on the principle of one-law-one-country. He is well known for his anti-Muslim propaganda, and like his clerical colleague, Ven. Galagoda Atthe Gnanasara, is understandably popular among Sinhala-Buddhist supremacists.

This group, on whose support GR-MR duumvirate is surviving, has no regard to the country’s pluralist make up and considers pluralism a bulwark and not aid to the economy and development of this nation. Therefore, once this principle is accepted by rulers, then cremation can be imposed upon all communities as the norm, even after the emergency passes away and in total disregard for a community’s religious and cultural susceptibilities.

This, I suppose, is the underlying fear behind Muslim concern about cremation. So far, and in spite of numerous other incidents such as the ones in Nelundeniya, Chilaw and Mahara, GR has not taken any step to allay the fears of this community. His inaction proves that he is in total cahoots with the supremacists.

In many ways one could see an attitudinal change in the behaviour of the community after some bitter experiences in recent years. Even in religious matters they have become flexible depending on the urgency of times. Therefore, why not make it categorically clear and public by GR and MR that once the emergency is over Muslims will be allowed to practice their funeral rites unmolested and unrestricted? What is preventing them doing so?

There is no question that the entire nation at the moment should throw its weight behind the Government. COVID-19 is the most immediate and relevant danger. It is also a menace that is driving the nation’s struggling economy to the point of total collapse. The twin crises of health and economy cannot be tackled without the full cooperation of all communities and people. Why not make this fight apolitical and appoint a multi-communal task force like a war cabinet with relevant expertise?

Regarding the economy, the populist measures hastily implemented by GR with an election in mind are coming to bite the nation now. The blanket ban on all imports is a mistake committed in desperation, and going to worsen the situation. Import restrictions have to be selective and they need to be part of a comprehensive economic plan covering multiple sectors.

Immediately, people have to be fed and cared for and government needs revenue. External borrowing is going to be difficult and more expensive, because even lending countries are facing financial constraints. Appeal to expatriate Sri Lankans to help with their savings should be appreciated, but what about the hoarded wealth of local men and women lying in tax havens?

There need to be two sets of measures, one to tackle immediate consumer issue and other for economic recovery after the emergency. This is the best opportunity to forget our ethnic prejudices and build Sri Lanka as a nation. Will GR stand up to the occasion?

(The writer is attached to the School of Business and Governance, Murdoch University, Western Australia.)