Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Tuesday, 14 February 2023 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Could the new appointees do differently if the current local government organisational setup remains the same? – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

|

Election fever

Sri Lanka is a strange country. Although its official name is Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, the people living in this country are having an intense debate whether to hold an election or not. A sane person would think that a democratic country cannot exist without exercising universal franchise periodically. It is something we exercise no matter how difficult our life is due to economic conditions.

Sri Lanka is a strange country. Although its official name is Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, the people living in this country are having an intense debate whether to hold an election or not. A sane person would think that a democratic country cannot exist without exercising universal franchise periodically. It is something we exercise no matter how difficult our life is due to economic conditions.

The need of holding an election is a no brainer to a democratic mind. Maybe it is a no-brain condition for the power-thirsty, intransigent people. The current situation is akin to a group of teachers and students having a debate whether any teaching must be done in the school. This is an island like no other.

In a country like Australia, an election is a set, social event in the government calendar. Public do not care about the individual nominees. They vote for the political party based on the policies of the party as the party is responsible for the performance of the nominee. How is the mood in the country during an election? There is no noise absolutely. Other than an occasional photo display in the front yard of a home supporting a candidate or a few leaflets sitting in the mailbox, the public do not see or feel any change in the environment. There is no visual or noise pollution or social disruption due to an election. There are political debates aired on the TV on policies on offer, for the interested parties to watch. Those debates are very civilised, and fact-based.

Anyway, the voting is compulsory in Australia. Not voting at an election attracts a monetary fine and not paying it on time would add more dollars to the fine. If the final fine is not paid, the defaulter must be ready to go to jail. I saw it happen at least once. In Sri Lanka, we have the freedom not to exercise the freedom of expression. It is a lopsided freedom.

Sri Lankans are now suffering from the election fever. I reckon that it is a good fever to have, to ensure the democratic institutions are alive and the democratic processes are continually being used to preserve human rights.

If (big ‘if’) the elections are held and the public representatives are appointed, the public expects them to manage the local government institutions properly and deliver the services and the benefits to the public efficiently and effectively. So far, the public representatives failed to do a proper job. Could the new appointees do differently if the current local government organisational setup remains the same? My personal assessment is “no”. If anyone wants to see a change, there should be significant operational reforms to the LG organisations.

In summary, we have 275 Pradesheeya Sabhas (PSs), 41 Urban Councils (UCs) and 24 Municipal Councils (MCs). Hence, in total, there are 340 public organisations to be managed. These are the organisations extremely close to the public. The quality of services delivered by these organisations would directly impact the daily lives of public.

Sri Lankan crisis

On 3 January 2022, I have published an article in Daily FT, explaining that the current economic crisis in Sri Lanka is a direct consequence of poor asset management practices across all public sector organisations over seven decades (https://www.ft.lk/columns/A-country-on-the-way-to-palliative-care-ward-Overview-of-an-oblivious-crisis/4-728544). This article has been translated into Sinhala and published in Lankadeepa newspaper, (without my prior knowledge). Although, I detected a few incorrect choices of Sinhala words for the asset management terms, I was happy that someone realised the importance of disseminating the information among the Sinhala readership.

However, the sad aspect of these efforts was that no one in the public sector so far acted upon the free advice. Maybe, they wanted a Caucasian consultant to advise them under a perks-studded foreign aid program. If an organisation does not have a vision and a strategic plan, no foreign country would be willing to assist and waste their resources.

Engineers and asset management

In Sri Lanka, we have competent young engineers. In general, they specialise in narrow sub-disciplines and make career decisions heavily on monetary rewards.

Life is all about taking calculated risks and making choices. As a professional I made my career decisions with a long-term vision. I wanted to be a jack of all civil engineering trades without specialising in a single sub-discipline. I knew my limitations. My intention was to exactly know what should happen to resolve an issue and who can do it. I would select an expert but I have enough knowledge that he or she cannot con me with wrong solutions. This career development path enabled me to make sound multi-faceted decisions. I always enjoyed practical solutions delivering benefits to the people which should be any professional’s duty.

Although I did not realise myself at the beginning of my professional journey, I was building the foundation to become an Asset Management Engineer. Only after I migrated to Australia and joined NSW State Government, I realised it, but I was technically ready to take over the asset management function.

In Sri Lanka, we have an acute shortage of Asset Management Engineers due to dual reasons; the non-recognition of Asset Management as an engineering discipline and the lack of formal education, guidance and training. One cannot become a true asset management engineer by specialising in just one aspect of asset management. The competencies required for an asset management engineer are a mix of strategic management, maintenance and reliability engineering, construction and manufacturing, risk management, data management, people management, financial management, economics and sociology.

Although the dominant physical asset management practitioners in the world are engineers, there are other professionals who practise asset management. Hence, the asset management has multiple owners. In my view, an Asset Management Engineer cannot call her/himself ‘an expert’ as the competency spectrum and the level of the knowledge required are being rapidly updated and always, there is a capability gap to be bridged by the practitioner. The asset management target moves further away constantly. So, it is a catching game. Hence the best approach would be to make the best possible decisions, based on the available knowledge, competency, facts, data and analytical tools and thereafter, make necessary changes when updated information, improved capabilities and new analytical tools are available.

There are many variables in asset management, and it is impossible to accommodate all variables into a solution generation model. Hence, the solutions are trialled and tested on ground, and the impacts and outcomes are observed. The solutions applied differ from the organisation to organisation as well. Hence, the asset management solutions applied to one organisation cannot be applied to another organisation readily as the asset management maturity in each organisation is different.

Public sector experience

Some life decisions are intuitive. One of my such decisions was to remain in the public sector to build a long career. Just five years into my professional career, I attended an interview conducted by the then heavy weights of the Sri Lankan engineering community and I performed satisfactorily. There were a few well-resourced organisations in the selection list, and I selected Ceylon Electricity Board (CEB) as my preference. The only hurdle was the availability of a single vacancy in CEB for a Civil Engineer. I was adamant that I wanted it. The Interview Panel tried to persuade me to list the Sri Lanka Ports Authority as my first preference. I politely refused and nominated my single preference. However, I was surprised and thrilled, when I got the offer in writing.

Then, my investigative traits kicked in and did a bit of research on the professional freedom for civil engineers in CEB, the management set up, who were there and the professional development opportunities. Without going into details of the findings here, I made an informed decision to decline the offer. It meant that I declined a lucrative salary offer.

During the next three decades, time to time, my mind revisited this decision and thought I made the wrong call. However, after seeing how the senior engineers of CEB struggled at the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) to defend their strategic planning and project management decisions and processes and further, when the new General Manager, Rohan Seneviratne (not a relative of mine, but a professional peer of mine worked at Randenigala/Rantambe Project) declared that CEB was bankrupt, I realised that my decision was right. If I were there, I would have been a lame duck in front of the COPE because I would have made similar mistakes, being a part of the operational set up and the organisational management culture.

By studying their answers to the COPE queries, I was certain that CEB had a long way to go on asset management because CEB would not have been at this current critical juncture if it had applied advanced asset management principles into their management process. I heard, in professional circles, that my first employer, the Central Engineering Consultancy Bureau was also struggling due to the direct impacts of the country’s poor economic situation and there were not enough planned major construction projects for assigning all currently employed engineers. It is said that these highly talented engineers would be re-assigned to other semi-government organisations with the option of topping up salary shortfall effected by the change. I suggest CECB Management to be more innovative and there may be clues in this article for their consideration.

I did a short presentation on Asset Management for CECB engineers around 10 years ago as a response to a personal request made by a Deputy General Manager, to raise asset management awareness among CECB management. However, I have no idea whether they took further initiatives to enhance the asset management knowledge among the engineers. If they have already developed asset management skills, my suggestions in this article would serve them well.

My focus today is to re-emphasise the importance of asset management for the public sector and to identify possible asset management roles in local government sector organisations for engineers to make a positive contribution. The truth is that all public sector organisations need the service of asset management engineer.

Personal interventions

I was in the local government sector for almost 30 years now, out of the overall 35 years in the public sector. Hence, I have high confidence in my understanding of how the Local Government Sector organisations perform in Sri Lanka and Australia, what their contemporary issues are and which solutions are to be applied.

A few years ago, I delivered a tailored Asset Management presentation at the Colombo Municipal Council and also an online webinar on the same at the Institution of Engineers Sri Lanka. Further, I once accommodated a high-level Sri Lankan Government delegation which consisted of a Sri Lankan Provincial Chief Minister and a Secretary to the Ministry of Public Service at my workplace in Australia and demonstrated to them the importance of asset management and current Australian applications.

After the demonstration I sent them important asset management documentation via email. I did not even get an acknowledgement to confirm the receipt of the resources. Hence, I don’t believe that they acted upon any of my suggestions and I could not see any improvement in Sri Lankan local government practices using newfound knowledge and exposure. Maybe I have unwittingly helped them to convert a holiday visit, to an official visit.

This article is another attempt to guide whoever is making decisions on the performance of local government sector organisations to incorporate asset management into daily operations.

Local government sector

In Sri Lanka, there are three layers of governance, viz; Central, Provincial and Local. I am yet to understand the role of Provincial Governance for a tiny country like Sri Lanka. In Australia, the area of New South Wales State is 12 times larger than Sri Lanka. If it had a provincial government system like in Sri Lanka, there would have been more than 108 Provincial Councils. In terms of average population per Sri Lankan province, NSW would have had four Provincial Councils. Australians were intelligent enough to have only 6 States and 2 Territories on a land 118 times larger than Sri Lanka, instead of having Sri Lankan style equivalent; 1,062 provincial councils.

I understand that there were ethnic and regional geopolitical influences behind this bizarre decision. However, it was a wrong solution for a legitimate problem. The solution should have been the proper operation of PSs, UCs and MCs, but of course, having a lesser number of those. This would have made the Provincial Councils practically redundant and the entire population including the people from the North and East would have unanimously demanded the abolition of non-beneficial Provincial Councils.

Hence, while disregarding any role to be played by the provincial councils, the local government could be considered as the most important governance layer within the three-tier governance hierarchy and this layer directly feels the public pulse.

The role of local government is multifaceted and complex in nature. The role depends on the country and the legislative structure. Hence, the following narrative is brief and aimed at the relevant scope of this article, which is asset management.

The local government entities are responsible for providing and maintaining basic public infrastructure facilities like roads, bridges, parks, community buildings, forests, cemeteries, etc. They facilitate public amenity and maintain quality natural environment and ensure public hygiene through sustainable waste management processes and strict food safety regulations. In addition, the local government entities have the role in enforcing land use and development planning regulations.

Of course, the public pays a price for local government service in the form of the council rates, but such a revenue is not enough to fulfil all public expectations. In Australia, the local government sector entities seek funds from the Federal and State Governments for major planned initiatives and the City Councils invest a part of their revenue in the commercial market expecting handsome returns for the investments. I understand that the investment of revenue without proper regulations, and checks and balances is a dangerous proposition in the corrupted Sri Lankan governance environment.

The current approach in resources hungry and management systems deprived Sri Lankan Local Government authorities is to deliver the minimum services, as a response to the public demands. Hence, the quality of service is even below the acceptable local standards, let alone meeting the internationally acceptable standards. The first casualty of this approach is asset management practices.

Asset management practices

In general, Sri Lanka does not have enough physical asset management practitioners. This fact was evident during my asset management presentations. Even, the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka has no specific recognition of asset management as a professional practice area or has a Sectional Committee for Asset Management while the developed countries have even Engineering Institution affiliated Asset Management Councils, predominantly led by engineers. I am a member of the Asset Management Council, Australia having the eligibility to apply as a Senior Asset Management Practitioner, in addition to the fellow membership with Engineers Australia.

NSW government approach

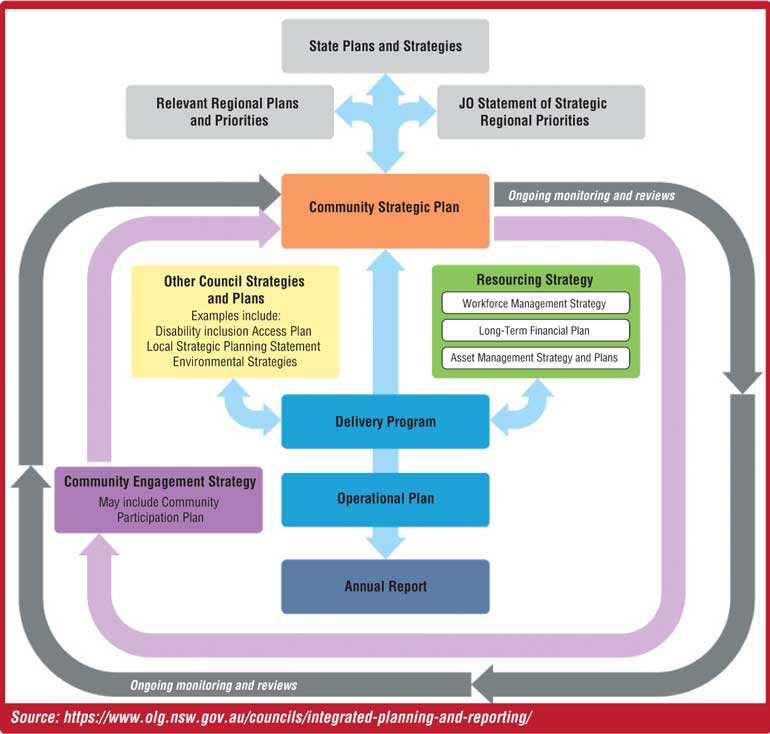

In NSW, Australia, the Department of Local Government has an Integrated Planning and Reporting Framework in place. All city councils must comply with the IPRF requirements. This framework ensures that all city councils’ functions are performed in accordance with the guidelines prepared by the NSW State Department of Local Government. Community is to be consulted periodically to identify their demands, expectations and needs. Thereafter, a 10-year Community Strategic Plan must be developed. This plan is reviewed and updated annually to ensure the plan reflects the current community needs.

All strategic plans developed in a council are interconnected with a specific set of reference numbers to ensure all are working together to achieve a common set of goals identified in the Community Strategic Plan. If such a link cannot be established, no funds will be allocated for implementation. A council usually investigates various public and asset related issues and develops action plans targeting specific areas such as transport, environment, elderly people, and less-able people, etc. However, if such plans cannot identify any link to the community goals, such plans are to be re-endorsed by the community before implementation. This means the community plan will be updated accordingly.

The Federal and the State Governments also develop Master Plans in consultation with a wider community. Councils’ strategic plans must have the cross references to these Master Plans to ensure Council actions are in line with the State and Federal Government plans. This way the entire hierarchy of governments are operating and moving towards one strategic direction in sync, without any duplications or conflicts of actions.

All public assets are managed in accordance with a sound strategy and an asset management plan. The funding for lifecycle management of assets is based on a 20 years lifecycle cash flow schedules for each asset class. The human resources are planned and allocated as per the Workforce Management Strategy and the Plan. Everyone in a city council has a specific role to achieve the strategic goals. When such roles ceased to exist, relevant staff are made redundant or reallocated to new roles only if they are the right people for the new positions.

The long-term Financial Plan is developed to fund development and maintenance of physical assets and the delivery of planned services. The funding sources are identified in advance. All services have pre-determined service levels set in consultation with the community, having analysed the Council’s capability and affordability to commit to such a service level. If funds are not available, the service levels will be decreased after public consultation. If the public insists on maintaining a certain service level without any reduction, either the council rates will be increased to fund the capability and affordability deficit with the approval from the State level authority by justifying the rate increase. Alternatively, a short-term special funding levy will be introduced, following due approval process.

Hence, all City councils will prepare a Service Delivery Plan, a Financial Plan and an Operational Plan. All plans are to be exhibited for public feedback before placing it in front of political arm of Council for the approval.

I do not expect the Sri Lankan Local Government Sector to implement this kind of well-coordinated planning mechanism overnight as this would require significant changes to the legislation, the organisational resources set up, data collection efforts and data analysis. However, it should be the long-term plan. In 2007, I was heavily involved in developing the first-generation asset management plans for my City Council and until today, I am involved with improving the asset management functions. Asset management is not a project but a journey. Any organisation should take baby steps before it starts walking.

A way forward

I am not sure about the current staff arrangements in Pradesheeya Sabhas and Urban Councils although I have a fair understanding of the organisational set up in Municipal Councils. I suggest all Pradesheeya Sabhas and Urban Councils to have an Information Administrator, Data Analyst, Asset Management Engineer, Environmental Management Officer and a Community Officer. All these position holders must be formally qualified with relevant tertiary degrees and relevant training. If available qualified staff are lacking training, it should and can be arranged.

Organisations like CECB has highly talented engineers who can be assigned to local government sector on-secondment basis to set the asset management processes. I believe Municipal Councils already have qualified staff to cover aforementioned positions. However, MCs should do more to help UCs and PSs. There should be an “adopt an LG kid” scheme. This means a UC should adopt a few PSs and a MC must adopt a few UCs in each administrative district. Human resources and expertise should be shared, and the management processes must be developed as a team. This is like a person adopts a child. A MC must care about the existence and survival of UCs and UCs must do same for the PSs. Ultimate aim is to serve people by all.

A set of guidelines must be prepared and issued to each local government entity (PS, UC and MC) for them to follow and plan the service delivery and to implement asset management functions. Assistance to develop the guidelines could be initially sought from the local professionals and overseas professionals working in the local and state government of developed countries. Such guidelines and action plans could be used for seeking monetary and technical assistance from international funding agencies for implementation.

(The writer is a Chartered Professional Engineer, a Fellow and an International Professional Engineer of both the Institution of Engineers, Sri Lanka and Australia. He holds two Masters Degrees in Local Government Engineering and in Engineering Management and at present, works for the Australian NSW Local Government Sector. His mission is to share his 35 years of local and overseas experience to inspire Sri Lankan professionals. He is contactable via [email protected].)