Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Wednesday, 27 April 2022 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

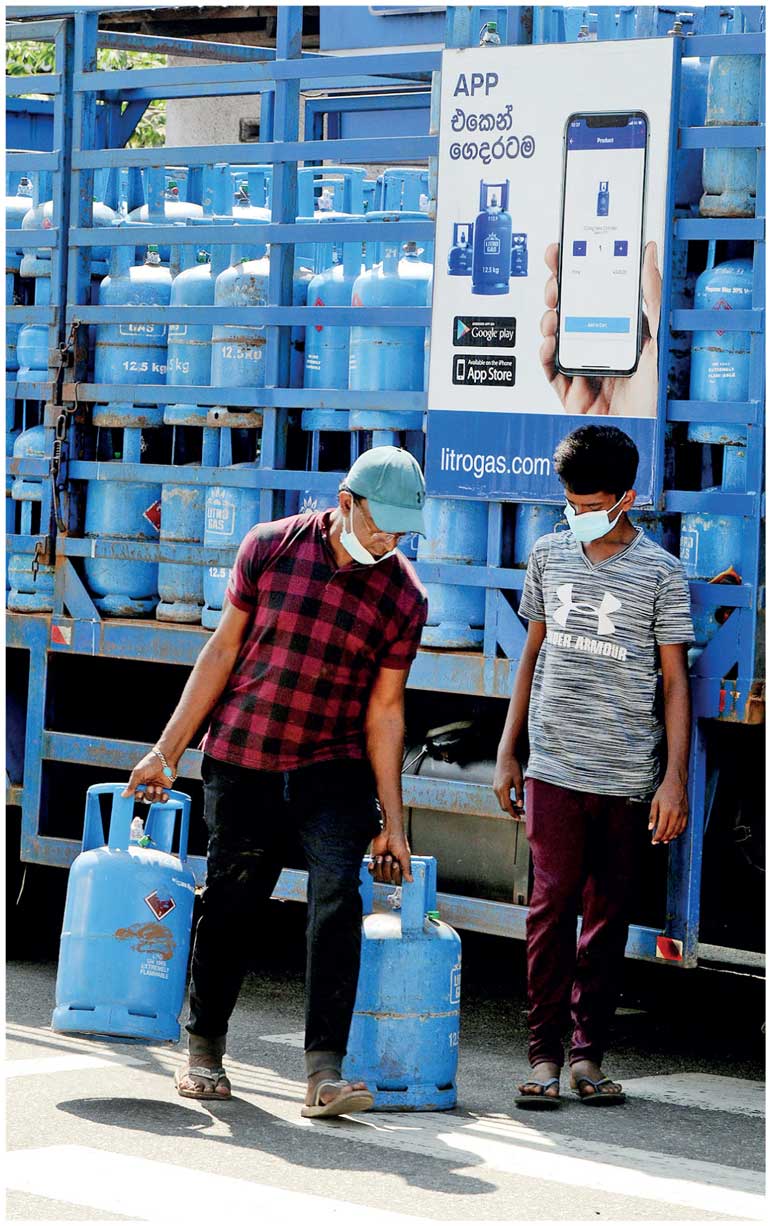

Like a pack of falling cards, the increases in gas and fuel together with the shortage of food have naturally caused sharp increases in food prices – Pic by Shehan Gunasekara

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of light, it was the season of darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” – Charles Dickens,

darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair” – Charles Dickens,

A Tale of Two Cities

Only two years since taking over, President Rajapaksa and his Government are accused of causing an acute dollar shortage, a balance of payment crisis and dragging the country deeper into debt by their excessive government spending, indiscriminate borrowings, large-scale tax cuts, corruption and mismanagement of the economy. The country is now teetering on the brink of an economic and social collapse.

The rupee is rapidly depreciating against the dollar, our dollar reserves are dwindling and the cost of living is rising in double digits. At the time of writing, inflation as at 31 March 2022 was 18.7% and the official selling rate of 1 US $ is Rs. 340.

Across the country, this economic crisis, has left parents struggling to feed, clothe and educate their children, led to loss of jobs, left families bereft of their savings and breadwinners frantically searching for jobs in a shrinking economy. It has effectively, pushed a large section of the middle class into the poverty line causing a huge shift in the socio-economic landscape of the country.

What does the economic crisis mean to the everyday person on the street?

Heavily dependent on imports for basic items, the forex crisis has resulted in a frightening scarcity of food, medicine, fuel and gas. The food scarcity is further exacerbated by the reduced agriculture harvest that is a result of the President’s shortsighted and ignorant directive to switch to organic farming overnight without any preparation or plan for such a huge shift in agricultural methods. The shortages of gas and fuel are so acute that it is now normal for people to spend entire days, waiting in queues several kilometres long, to obtain gas and fuel.

The strain this places on the people is so great that people have collapsed out of hunger and exhaustion while standing in these queues and eight deaths have been reported thus far. The price of fuel double triple within weeks and the price of a gas cylinder has soared to levels unaffordable for the ordinary consumer. Since electricity generation in Sri Lanka is largely from thermal power, fuel shortage has also resulted in insufficient power generation leading to power cuts that have lasted as long as 12 hours.

Like a pack of falling cards, the increases in gas and fuel together with the shortage of food have naturally caused sharp increases in food prices (the food inflation as at 31 March 2022 was 30.20% with predictions of further increase). It is now not unfamiliar to hear that children have gone months without a drop of milk due to both the shortage and the exorbitant price of milk powder and fresh milk. The tragic report of the father who committed suicide unable to feed his hungry children highlights the severity of this issue; and through this crisis looms another silent threat – an entire generation of malnourished children.

The economic crisis has also severely affected household income. Those who ran small-scale businesses such as restaurants, tailoring shops, home catering and cab services have been forced to shut down due to the shortages of fuel and gas, electricity shedding and the unaffordable prices of food items. Most informal sector workers such as domestic workers, gardeners and care takers have been laid off simply because, given the rising cost of living, employers can’t afford to employ them anymore.

For a government that rode on the goodwill of farmers, it has failed to sustain the farmers who are now stumped, unable to sow paddy without seeds, fertiliser and fuel for the tractor, foretelling a doomed season of rice scarcity and economic struggle for the farmer.

The #GoHomeGota movement and the Government response

In this nightmarish reality people have taken to the streets, every day, across the country, demanding the resignation of the President and his Government with the now familiar slogan #GoHomeGota2022.

The President, however, informed Parliament that he will not resign. Instead, in early April, his entire Cabinet resigned. Displaying the Rajapaksas’ complete disdain and disregard for the people, the Rajapaksa brothers decided to retain the two key positions of Government, President and Prime Minister, with them.

The people continued protesting, vociferously, demanding the resignation of the President, the Government and all members of the Rajapaksa family, the return of wealth illegally amassed by the Rajapaksa family and holding them accountable for corruption.

Nevertheless, after the Sinhala and Tamil New Year, displaying unimaginable levels of apathy and contempt towards the people, the brothers returned with a vengeance announcing the appointment of a full cabinet. Thus, signalling that they intend to stay put. President Rajapaksa, addressing the nation, with his trademark cavalier attitude, made a statement of fact that, it was a mistake to ban fertiliser overnight and Sri Lanka should have sought the assistance of the IMF much earlier, but, he proffered no apology and certainly took no responsibility for his failed leadership.

The President and his Government have been trying various methods to suppress the protests. At the very first mass civilian protest, which took place in Mirihana, police power was unleashed. Protestors were assaulted and arrested. That weekend the President declared a state of emergency and imposed curfew in an attempt to restrain the protests. The people, however, peacefully protested in pockets outside homes and in towns. When curfew was lifted, strong waves of protests took place ending with the protestors occupying the Galle Face Green chanting slogans of protest, continuing now for the 15th day.

President Rajapaksa then turned to his elder brother – the Prime Minister, who addressed the nation on 10 April. Contained in his speech were references to the 89/90 youth uprisings and its violent repercussions. Clearly there was a strong message there, sent to the youth who are largely sustaining the protests.

The protests are now rapidly gaining momentum amongst the public servants, farmers and the working class outside of Colombo. This unnerves the Government. Prostituting death and destruction to hold onto power, the Rajapaksa Government opened fire on an unarmed civilian protest in Rambukkana, killing one person and critically injuring many others. Their only offence: protesting against the Government for the rising cost of living, which was making it impossible for them to feed their families.

No amount of veiled threats, curfews, declarations of emergency, or police brutality can suppress the #GoHomeGota2022 movement. It is the rising of a nation, against its Government, laying bare an entire nation’s helplessness, anger and fears of an uncertain future.

Where to now, politically?

At the time of writing, Sri Lanka is at a political impasse. The President is steadfast in his refusal to step down and the people are unrelenting in their demand for his resignation. The Government itself is walking tight-rope. President Rajapaksa’s coalition seems to have deserted him and there are calls from within Government for the Prime Minister to step down. There is talk of fresh discussion about the defected MPs supporting a no-confidence motion.

But, what of the Opposition itself? They have failed too. In this critical time of a severe economic and social crisis, they have failed to put on hold their personal ambitions and set aside their political and ideological differences to adopt a unified voice pushing the agenda of the people in Parliament. The people, increasingly frustrated with the politics in Parliament, are calling for all “225” in Parliament to be replaced with new, young “clean” politicians.

However, as much as we would like to see the backs of the “225+1”, unfortunately, we cannot execute a Bolshevik style revolution and have the president and all 225 members of parliament removed in one fell swoop. The Constitution is the highest law of the land and the repository of the sovereignty of the people. No action taken outside the parameters of the Constitution has ever been legitimised in the history of Sri Lanka and we must preserve this legacy.

Therefore, unseating the president and changing the regime, however impatient we are, must happen step by step through constitutional means. Any measure outside of the constitutional provisions will create even more turmoil, dragging the country into an abyss of economic collapse and social fragmentation, from which it might not recover and we could become prey to the geopolitical interests of the bigger guns in the region and across the sea or be taken over by military rule.

The current political instability however, is also one situation Sri Lanka can ill-afford at the moment. According to the IMF Article IV Consultation, the sovereign debt to GDP ratio of Sri Lanka in 2021 was 119% with predictions of it increasing in 2022, Sri Lanka had been blacklisted in the international market as far back as in 2020 and on 11 April 2022 Sri Lanka declared that it is no longer able to furnish its debt payments confirming its sovereign debt default status.

In the circumstances, it is now abundantly clear that the only way to prevent a complete collapse of Sri Lanka is to obtain an IMF bailout and restructure the debt repayments; however, the current political instability and social unrest is a major factor that will delay this process. For, in simple terms, who would want to negotiate with a government whose continuity is uncertain and legitimacy is questionable, because whom can they hold responsible to carry out the conditions necessarily accompany an IMF bailout?

If the IMF is to bail out Sri Lanka and debt repayments are to be restructured, Sri Lanka needs to show the certain possibility of economic growth but who can be certain of economic growth in a country embroiled in social unrest with a government that has lost its mandate?

It is impossible for Sri Lanka to conduct elections right now. We do not have the money or the resources. Then, what alternatives do we have? The ideal scenario is for the President to respectfully resign his office as provided in Article 38(b) of the Constitution. Article 40 of the Constitution provides for the appointment of a new President for the remainder of the term of president, elected by members of parliament from and out of the current members of parliament. However, this does not seem a viable option.

It is therefore, entirely up to Parliament, “the 225”, as elected representatives of the people to organise the consensus of parliament towards what the people want. The Constitution provides for the impeachment of the President as set out in Article 38(2). However, it primarily requires the support of a two-third majority of the whole parliament (that is, 115 out of the total number of 225 members of parliament.), which is, in itself, a challenge for it will require a great deal of work, commitment and unity from an opposition that has yet not been able to forge a unified voice.

Firstly, as per Article 38(2) a resolution calling for the impeachment of the president must be tabled containing either the signatures of not less than two-third members of the whole parliament or signed by half of all the members of Parliament and sanctioned by the Speaker. The impeachment must be based on one of the grounds set out in Article 38(2)(a), which includes bribery and, misconduct or corruption involving the abuse of powers of office. This resolution, calling for the impeachment, should be passed by not less than a two-third of the whole parliament. Afterwards, it should be referred to the Supreme Court for an inquiry. In the event the Supreme Court finds the President guilty, parliament can remove the President after a two-third or more of the whole parliament votes in favour of a resolution to remove the President.

The other option provides an honourable way out of this mess for the President and responds to the demands of the people. He can give his blessings to abolish the executive presidency by constitutional amendment and remain as non-executive president for the remainder of his term. However, this proposal is also not without its hurdles. Firstly, such action requires of the President a great deal of political courage, chivalry and will, qualities, unfortunately, absent in President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Secondly, Field Marshall Sarath Fonseka gave voice to the belief, possibly floating in parliament, that the executive presidency is not in fact the devil it is portrayed to be and the country would benefit from it. Thirdly, there is a school of legal thought that abolishing the executive presidency requires a referendum, which we cannot afford right now. Fourthly, there is also doubt as to whether Mahinda Rajapaksa, who harbours presidential aspirations for his son, will support this amendment. If he touts against this amendment, securing votes from the government party would prove difficult.

The last resort would be a negotiated political settlement? The SJB have already proposed the repeal of the 20th Amendment in favour of a 21st Amendment, which will effectively restore the 19th Amendments with improvements (the 19+). In a nutshell, it will primarily reinstate power in parliament, resulting in the government being unanswerable to parliament, reduce and limit the powers of the president, and establish the independent commissions. The defecting party of government has also submitted their proposed amendments. In the circumstances, this not a feat that, either the SJB or the defecting MPs can achieve on their own. Judging from the Supreme Court direction of last time, the constitutional amendment will require a two-third majority in parliament. A tug of war between the SJB and the defecting MPs over the proposals is not unlikely.

However, Mahinda Rajapaksa and his son, Namal Rajapaksa, would most likely support the amendment, as they are keen to clean up this political mess as soon as possible in order to salvage whatever is left of any possible political future for Namal Rajapaksa. Their support to the proposal will also garner the support of the Government MPs.

However, both these constitutional reforms have the potential to run into an iceberg – the question of wrestling the Premiership from the grips of Mahinda Rajapaksa. He has publicly declared that any government should be formed under his premiership and MPs loyal to Mahinda Rajapaksa are working frantically to obtain the signatures of more than 113 MPs to prove that the Premier still has support of Parliament.

If we are to succeed in having the entire Government removed and a new Prime Minister appointed, any proposed Prime Minister must be able to command the majority in Parliament, as the governing party is unlikely to allow a minority government to take the reigns. This will again require a concerted effort and unity by the opposition.

So, we are back to the central issue of Opposition unity. Fundamentally, there has to be negotiations, discussion and unity on the part of the Opposition in Parliament if we are to get rid of the Rajapaksas and their Government.

What can we do?

Firstly, as protestors we have been focused solely on pressuring the President to resign. We should also direct our pressure to the other members of parliament, including those members of the Opposition. These are the people’s representatives and their mandate is to carry out the will of the people. We must organise and exert pressure on the 225 parliamentarians to set aside their political ambitions and political differences to unite and further the people’s cause in Parliament ending this political deadlock.

Secondly, we must also be aware of what we want after Gotabaya Rajapaksa and his Government is sent home? We need to situate back to the IMF bailout and the economic crisis. What would be sensible (and beneficial) is to obtain the IMF bailout and debt restructuring with the collective approval of this Parliament. This would ensure the collective responsibility of all parties to any commitment made with the IMF. In addition, it would also prevent, come elections, contesting political parties, in order to gain political mileage, pointing the finger at one single political party for the hardship people will have to endure as a result of the austerity measures of an IMF bailout. That is not a benefit we should afford any one of them.

In this context, we should call for a multiparty interim government till the country is stable enough for an election. The urgent need for the Government and Ministry Secretaries to be comprised of professionals with experience and expertise, establishing an independent commission for procurement as well as transparent and accountable auditing of government needs no argument. The political parties can use the national list quota to introduce to government specialists with expertise upon seeking resignation of persons already appointed.

For today, everyone must forsake their private ambitions for the good of the country. A multi-party government is also crucial as political parties who will look after the interests and welfare of the different segments of society such different ethnic groups, persons with disabilities, low income groups, etc. must be present in current national policy making, responding to the economic crisis and IMF bailout.

We do not want “the 225” but we do need a government to run the country till we go in for elections to remove the 225. The best-case scenario therefore, is a multi-party interim government, IMF bailout, some semblance of stability and then elections.

(The writer is an Attorney-at-Law and Researcher, Barrister (Licolns Inn), LL.B (Leeds), LL.M (HKU).)