Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Monday, 21 November 2022 00:02 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

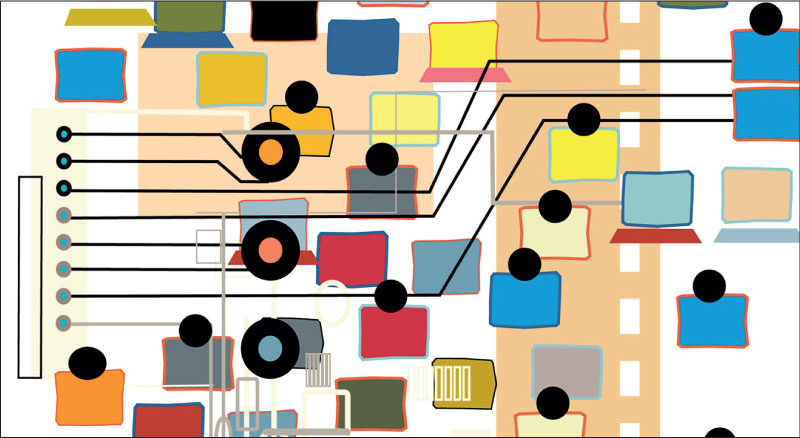

As we often observe, the future of work is hybrid. It is also through workplace ecosystems. Are we geared to such a transition? I came across an interesting article by three veterans recently published in the Sloan Management Review who argue that “workforce ecosystems can help leaders better manage changes driven by technological, social, and economic forces”. Today’s column attempts to reflect on it and relate its contents to local context.

As we often observe, the future of work is hybrid. It is also through workplace ecosystems. Are we geared to such a transition? I came across an interesting article by three veterans recently published in the Sloan Management Review who argue that “workforce ecosystems can help leaders better manage changes driven by technological, social, and economic forces”. Today’s column attempts to reflect on it and relate its contents to local context.

Overview

Elizabeth J. Altman from University of Massachusetts together with Jeff Schwartz & Robin Jones, Senior Consultants of Deloitte and Lowell and David Kiron, an editor for the Sloan Management Review have recently published an article titled, “The future of work is through workforce ecosystems”. As they observe in relation to the Western world, “Today’s workforces include not only employees, but also contractors, gig workers, professional service providers, application developers, crowdsourced contributors, and others.” Here the gig work refers mainly to independent contractors, online platform workers, contract firm workers, on-call workers, and temporary workers with formal agreements for providing services.

Why we need to consider an ecosystem perspective is an interesting question. It requires us to have some understanding of what an ecosystem is all about. An ecosystem can be described in multiple ways. The typical biology textbooks call it a community of living organisms. It can further be described as a group of interconnected elements, formed by the interaction of a community of organisms with their environment. It appears that the business world has borrowed the term from biology and adapted it to suit the business needs.

As such, it can be viewed as any system or network of interconnecting and interacting parts. The essential feature of an ecosystem is the lively interactions among the elements. It is a dynamic set of interrelationships that create value. An ecosystem can be influenced by internal as well as external factors. The scope and the space of an ecosystem may vary. In fact, the entire planet has been identified as a mega ecosystem.

The authors of the above said article, based on their global studies, appropriately adapt the concept in defining a workforce ecosystem as a structure that consists of interdependent actors, from within the organisation and beyond, working to pursue both individual and collective goals. As they observe, managing a workforce ecosystem goes beyond efforts to unify the dissimilar management practices currently organised around employees and non-employees. In fact, it is a new approach to a new problem that demands a fresh solution.

Four shifts towards workplace ecosystems

The authors direct our attention towards four shifts that propelled the creation of workplace ecosystems. They cover a wide range of aspects including diversity of workforce and distribution of work.

Shift 1: More non-employees are doing more work for business

Based on the authors’ estimates, non-employees are responsible for performing more than 25% of work in the enterprise. Many sources indicate that this dependence is expected to grow, facilitated in large part by a rise in platforms that make it easier to engage workers for on-demand, task-specific work (a type of work that is itself expected to grow). This shift coincides with another: growth in the number of highly skilled creative or technical workers (such as data scientists) who prefer to work on specific types of projects for one or more companies.

Such a shift may lead to several strategic challenges as observed by the authors. A majority of organisations report that they “inconsistently manage or have no process to manage alternative workers” across functional domains. Also, access to a greater variety of workers intensifies the need to make strategic choices around whether to recruit or temporarily engage people with new skills and capabilities. Further, maintaining an organisation’s alignment with its values and creating a consistent culture can become even more difficult when large proportions of the workforce are not adopting a workforce ecosystem can enable managers to make an integrated set of choices about these challenges.

Shift 2: The nature of work is evolving

“Job descriptions anchor traditional management systems,” opine the authors. Semi-annual reviews and annual merit increases are predicated on employees remaining in jobs for extended periods and generally pursuing prescribed, linear career paths. As they comment, “However, we are not alone in seeing a shift toward more short-term, skills-focused, team-based work engagements in which automation and technology free up people’s capacity.”

“At the same time, we are also seeing compensation approaches under pressure as people increase their skills and their expectations for increased opportunities and income,” observe the authors. In response, companies are adopting internal talent marketplaces so that employees can move fluidly through an organisation, building skills and gaining experiences without having to seek opportunities externally.

When these marketplaces simultaneously empower employees and create robust opportunities for managers to find talent for specific projects, they become “opportunity marketplaces”. An outsourced ICT operation in Bangalore catering to USA market could be an example. As the authors further observe, “A workforce ecosystem structure enables organisations to extend internal markets to incorporate external workers.”

Shift 3: There is growing recognition that a diverse and inclusive workforce can deliver more value

“More diverse and inclusive workforce leads to better outcomes continues” has been a reality revealed by research. Our authors are of the view that “by adopting a workforce ecosystem structure, especially one enabled by digital collaboration technologies, organisations can attract candidates they have never seen before”. Opening opportunities to workers of all types, including those who can engage in short-term projects and who may be geographically dispersed, connects companies with people of varied backgrounds, races, ethnicities, gender orientations, and abilities.

According to an executive at a global professional services organisation, based on our authors’ research, had relayed that because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the company moved its internship program online, enabling it to offer three times the usual number of internships. It also relaxed constraints on geography and expertise levels. As a result, it attracted a startlingly more diverse internship cohort. From this expanded cadre, the organisation will likely hire (and retain) a group of more diverse employees in the coming years. Its wide-ranging approach to virtual internships opened managers’ minds to accepting different types of candidates.

Shift 4: Workforce management is becoming more complex

“Organisations have started to change how they engage external IT workers,” opine our authors. More recently, companies are not only using contingent resources in IT, but also leveraging them widely in areas such as marketing, R&D, human resources, customer service, and finance. As they further state, “Organisations typically have separate, unintegrated approaches to managing internal versus external workers.” Responsibility for internal employees rests with HR, while procurement and other departments orchestrate external workers. Few organisations manage or can see their entire workforce in an integrated way.

“At a governance level, questions addressing the entirety of an organisation’s workers tend to go unanswered,” state the authors. They highlight it as a key problem. During the COVID-19 pandemic, one organisation required an accurate worker count to address pay continuity, absenteeism, IT requirements, and benefits needs for its newly remote workforce. Managers quickly realised that it was impossible to calculate the total number of workers. HR could provide an employee head count, but no one had a full view of everyone contributing to the company; the process of engaging workers was just too decentralised.

According to our authors, “A workforce ecosystem approach can address this issue by raising governance of the entire workforce to a higher organisational level, such as the board of directors and the C-suite.” In addition to helping ensure that critical management processes are deployed in a coordinated fashion, adopting a workforce ecosystem allows leaders to consistently take measures so that organisational values and norms are considered and applied across worker types.

As the authors observe, “The most forward-thinking companies are adopting workforce ecosystems that implement cross-functional systems, including HR, supply chain/procurement, business unit leaders, finance, and others.” For example, some organisations offer development opportunities not only to their own employees but also to those in their greater ecosystem community. Others recently extended pay continuity to external contributors. Additionally, we see opportunities for businesses to create strategic partnerships with labour platforms, enabling a more integrated and accelerated process for managing their overall workforces.

Workforce ecosystems and strategy

Designing and developing workplace ecosystems should be a core activity intertwined with corporate strategy. As our authors observe, “Executives face critical choices about how to manage their workforces.” They can either continue to manage employees and non-employees through different, and often parallel, systems, or they can develop a new, more holistic workforce approach that spans different types of workers and capabilities.

The authors claim, according to their research, that the workforce ecosystem approach has many strategic benefits. With workforce ecosystems, executives can both identify and develop interdependencies among employee and non-employee workers. With regard to Sri Lankan scenario, we need to have a cautionary approach in handling issues involving labour laws, worker benefits, diversity and inclusion, and organisational culture. Still, this integrated perspective enables more efficient and effective collaboration among workers, which in turn enables new perspectives on what work is possible for the organisation. As the authors aptly point out, workforce ecosystems flip a perennial strategic question. Instead of (only) asking, “What workforce do I need for my strategy?” workforce ecosystems enable leaders to ask, “What strategy is possible with my workforce?” This indicates a clear shift in focus with a wider range of choices available.

Way forward

Sri Lankan workplaces facing multiple challenges amidst an ongoing economic crisis can view workplace ecosystems as an opportunity to be cost-effective in a balanced manner. With a set of archaic labour laws and conventional minds hampering growth, it will be a challenging task. It is encouraging to see that some of the ICT firms have already started moving towards such work arrangements.

(The writer is the immediate past Director of the Postgraduate Institute of Management. He can be reached through [email protected], [email protected] or www.ajanthadharmasiri.info.)