Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Thursday, 14 December 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Ramanathan (not his real name), a land owner, received a letter from the Govi Jana Sevaya, stating that his fields and some bare lands have not been cultivated for several years. He wrote back stating the reasons and was requested to attend a meeting with the field officer on a scheduled date at 10 in the morning.

Ramanathan, an elderly gentlemen in his sixties, went on the appointed time and date, only to find the said field officer had gone to a funeral. This is the real state of affairs at the grass root level when it comes to agriculture.

The current land use arrangement in Sri Lanka dates back to the British era where export-based commercial plantation agriculture was superimposed on traditional subsistence farming. After the fall of the Kandyan Kingdom in 1815, the British Government consolidated its power and grip of the economy with the Crown Land Encroachment Ordinance in 1840 where more than 90% of the land was vested with the Government, and such State land was known as Crown Lands. This was the beginning of the peasant landless problem.

Today after 177 years, the State still controls 82.3% and the privately-owned land is 17.7%. As a result 27% of the peasants are landless; for those who own land 42.4% own less than an acre. Private holding of land was affected by the Land Reform Law of 1972. This act nationalised the most productive private lands, during a period of three years from 1972-1975 land extent of 419,100ha was vested to two state corporations; Janatha Estate Development Board (JEDB) and State Plantation Corporation (SPC). This reduced private holdings even further.

Landless problems have led to encroachment of State land and the victim has been Sri Lanka’s forests. In 1900 the population was 3.5m and the forest cover was 90% and today forest cover has receded to 29.7% with an estimated population of 21m in 2017. This landless problem is a serious matter where approximately 600,000 hectares (9%) of the total land area has been encroached.

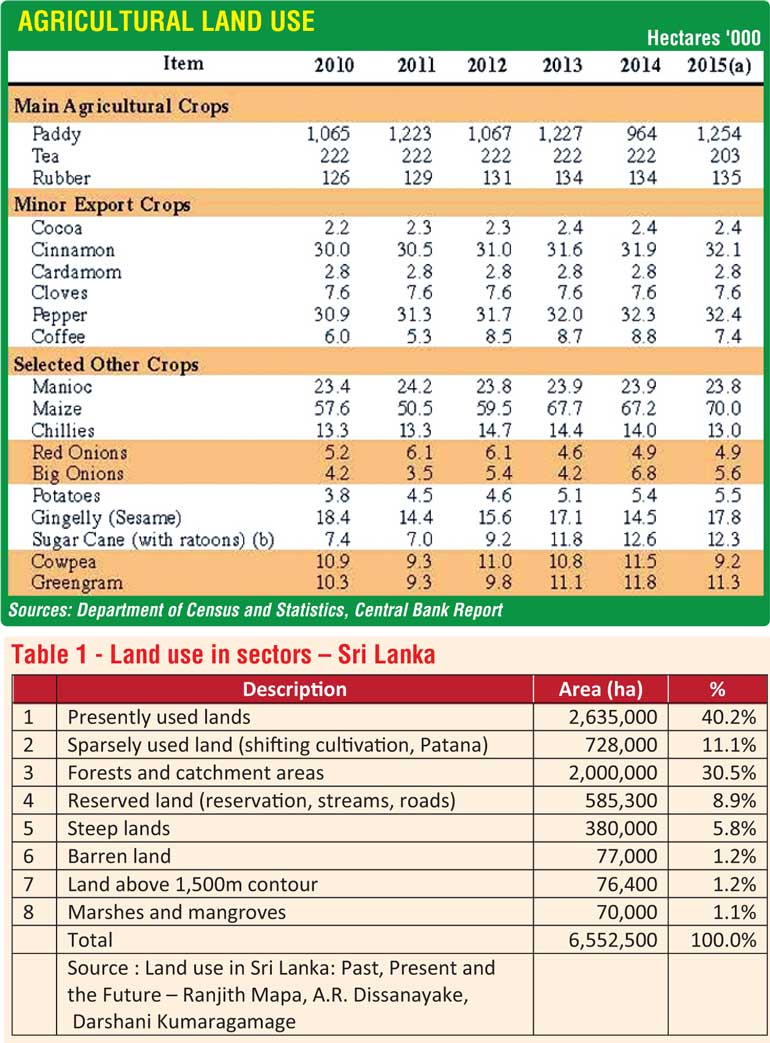

Sri Lanka’s land area is 6.55m hectares of which only 50% is arable. The country is characterised with a plantation  and non-plantation sector. Non-plantation agriculture comprises rice, maize, vegetables, fruits and other crops (Ayurveda and medicinal plants, spices, etc.). Out of 2.5m ha of agricultural land 80% is used for non-plantation food crops grown on small land holdings.

and non-plantation sector. Non-plantation agriculture comprises rice, maize, vegetables, fruits and other crops (Ayurveda and medicinal plants, spices, etc.). Out of 2.5m ha of agricultural land 80% is used for non-plantation food crops grown on small land holdings.

Approximately 1.65m small land holders operate on less than 2ha (five acres) and contribute to 80% of annual food production. Non-plantation agriculture depends heavily on irrigation and two-third of the land is in the dry zone, whereas plantation sector depends on the monsoon rainfall and is located in rain fed areas, mostly in the south west and the central mountains of Sri Lanka.

Any person travelling by train or bus will observe that many fertile land are not cultivated. Most land overgrown with weed and in an unsatisfactory state. It’s easy to blame the farmers. This is what happens when the public does not understand the deep problems of the small-scale farmer.

Generally, people believe that farmers are not cultivating due to the drought, floods, lack of capital and being downright lazy. In fact none of this is true.

The Sri Lankan agri sector is the hardest working sectors, where over 28.7% of the labour force is involved and has to toil in the sun and despite calamities of nature. Saying this, there is a contradiction, where hard work has proved low productivity contributing only 8% to GDP. Among SAARC countries Sri Lanka has the lowest GDP contribution from agriculture.

Why are our farmers not cultivating? Lately the authorities have orders to threaten to acquire uncultivated lands. Hopefully this is only a threat, because taking away the land will increase poverty, loss of livelihood and landlessness.

The greatest threat to farmers is from wild animals. Wild boars, porcupines and monkeys are destructors of crops in large quantities. These animals have no predators and our legal system protects these animals with wildlife laws. Unable to cultivate means losing one’s livelihood and falling into debt and poverty. As it is 25% of Sri Lanka’s population is nearly poor, earning just $1.50 per day and below $2.50 per day.

To make things worse, Wildlife Department officials capture monkeys in one area and release them in jungle areas close to villages. In no time these animals find their ways to the village and start “monkey problems” in the village. They not only run on roofs and peep through open windows but become an economic problem when they start destroying crops on the field and trees.

Many a home gardener would have the bitter experience of having his crop eaten by porcupines. Generally porcupines simply chew the plants and do not eat it. It is even more painful to realise that the plant was destroyed rather than eaten.

An article on 4 November in the Daily Mirror (page A7) has an article that says “Monkeys wreak havoc in Kegalle”. This article says a 30 ft long petition was submitted by 500 farmers and agricultural officers says there were 80,000 monkeys in 3,000 troops in the area. The request was to obtain shotguns from the authorities. It is a trend that will have future social implications.

Farmers have taken the law into their own hands and become “vigilantes” by using high tension electricity, trap guns to kill wild boars. This indiscriminate killings has cost the life of many an innocent man, deer, dogs and cattle. Some have made “grenades” laced with meat to trap boars. This is called “hakka pattas” and is popular among farmers. This too has cost the life of children and innocent animals.

In the north east, the human elephant conflict has had a heavy cost in terms of life, livelihood and territory. This is an area sociologist and wildlife officers need to solve with clear policies on land allocation to farmers in elephant habitats. It has become a national problem and debated in many forums and in Parliament. Feeble attempts to solve the issue has angered the population and cost the elephants dearly. This issue has to be solved by experts.

The Sri Lankan farmers are a discouraged lot. It seems nobody is on their side, primarily weather, Government agricultural officials, successors from family members to carry on farming, market prices, transport and many more. Since the farmer does not determine market prices, the middle man earns the most while the toiling farmer gets a pittance. Since the commodity is highly perishable, the farmer has to sell at the price commanded by middlemen. Lack of storage facilities has been a major problem for lower agricultural prices in general. Many a time the farmer does not get his Return on Investment and ends up in debt.

Sri Lanka is an ageing nation where 12% of the population will be over 65 years in less than a decade. Most farmers today simply don’t have the vigour and vitality due to age. They followed their parents’ footsteps and have low educational achievements. However, accessing family members or hired hands who are better educated to farming has been a failure, Today’s younger generation dislikes farming and prefers a Government job or a job in the services industry. This leaves the farmer to work the plot on his own or with his ageing spouse.

Sri Lanka’s agricultural policies are complex, misunderstood, unpredictable and sometimes contradictory. Many lands today are unused or underutilised. Land owners are reluctant to lease the land to farmers on a profit sharing basis. The owner fears that the farmer who cultivated the land for several seasons will go to courts and litigate and claim part of the land or the full extent. This uncertainty makes the owner keep the land fallow, thereby depriving the land owner and the farmer of an income and the nation economically. Conflict resolution with the present legal system takes too long. The land could stay idle while a court case drags on for years.

The administration and management of land in Sri Lanka is governed by more than 39 operational laws. Laws are vested with the Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Lands and even departments such as Irrigation Department. Currently land use policies are implemented on an ad hoc basis. There has been no recent study on land use and a mapping of agricultural land based on crops. The major drawback has been the limitation of robust data. With such reliable data future land use planning could be formulated. Innovative thinking must be utilised to achieve a reliable methodology to optimise land use.

Another problem is there are six Ministries involved in agriculture, most of them working independently and not communicating to optimise synergy to consolidate agriculture development. This fragmentation has a heavy cost to the farmer, the nation and ultimately agriculture suffers. The ministries are:

1. Ministry of Mahaweli Development

2. Ministry of Fisheries and Aquatic Resource Development

3. Ministry Plantation

4. Ministry of Agriculture

5. Ministry of Irrigation and Water Resources

6. Ministry of Land

Future agriculture strategies must take into account these six key stakeholders. One must eschew party and political ideologies to set up a frame work of cooperation for Sri Lanka to achieve success.

Between 2002 and 2012 Sri Lanka’s poverty was reduced from 22.7% to 6.7%. Given that Sri Lanka was only recently liberated from a 30-year ethnic conflict, it’s a credible achievement. Sri Lanka has achieved United Nations Millennium goals in areas of poverty elevation and improving sanitary conditions. However, despite great strides in health and education, this nation has remained poor and primarily agricultural.

As mentioned earlier in the article, Sri Lanka’s population has remained nearly poor. The Yahapalanaya Government has identified that agriculture will be a game changer. Better understanding of the rural population and improving living standards, including improving women economically has been the aim of this Government. Yahapalanaya’s New National Program for Food Production 2018 is the first step. It has to be a Public-Private Partnership (PPP). In this case the Government has to engage a partner (farmers) who are not business savvy unlike in a traditional PPP where the private sector is on equal footing.

To reduce inequality and poverty, the Government needs to give priority to agriculture in areas such as land usage, land encroachment, training agricultural workers, improving agricultural productivity, agricultural strategies for domestic and export markets, mechanisation, improving supply chain, evaluating tariffs, tax policies, fertiliser subsidies to be reduced by organic fertiliser, crop diversification, improving dairy and poultry farming, value addition to agricultural products, economic impact on sustainable agriculture, research and development on crops, studies on climate change, soil erosion and degradation, infrastructure development to reduce perishability, reduce wastage, and build storage facilities to provide all year round fruits and vegetables.

All this is possible if the Government has a clear mandate to frame policies with regulatory frame work where food is safe to consume and create market-oriented agri-economy. With such far-reaching policies, Sri Lanka’s agriculture will rise to a new plateau and reduce poverty and bring Sri Lanka to a Higher Middle Income bracket. This will be in line with the Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s Vision 2025.

Public day is on a Wednesday and the villagers wait for this day to meet a specific officer. Many a time such officials are not available. These officials are tasked with mundane things of local politicians. Most of these officials spend a lot of time away from office conducting political work especially when an election is on the horizon. This politicised culture has hurt the Sri Lankan economy.

Even after all these years Sri Lanka’s non-plantation agriculture is on a diminishing return. Paddy production increased due to large amounts of land made available after the war. These officials are very friendly and cordial. They know everybody in the village and are on familiar terms of calling the villagers aiya, mama and many endearing terms. Despite being friendly they are not useful. Nobody complains; the worst part is, where does a villager complain about Government officials? So the common man grumbles and suffers silently and meanwhile agriculture gradually declines.

Just take the spice industry, a major foreign exchange earner, but every year the yields are dropping. There is no sustainability and more small-scale farmers plant a few hundred pepper vines in their existing plots. It must be encouraged that every village household should have a pepper creeper and a cinnamon tree in their garden, just like the coconut, banana and the jack tree. This is not much to ask from a village household. The benefits are enormous to the nation. The question is, where is the effort?

If the above far-reaching policies are to be implemented, Sri Lanka’s Ministry of Agriculture needs a new breed of agricultural officers at the grass root level. My opinion is that the current officers are not trained to the task. A special training programme by the Agriculture Ministry affiliated with a university to teach the above mentioned specialised value added subjects. A new cadre of qualified officers must be groomed to this huge task. They must be placed on a district and divisional level.

Strategies must be framed to set the industry to increase yield, bring down food prices, higher protein intake to the populace, export opportunities, improve agri knowledge, higher employment and higher income to improve rural standard of living.

It must be noted that Thailand where the country was not colonised, the State only owns 20% and privately-owned land is 80%. Between 1962 and 1983 agriculture grew by an average of 4.1% a year. During this period the Thai economy employed 70% of the labour force. This was a time when the State focused on agriculture to realise their plans for future industrialisation.

The country developed other sectors; agribusiness was highly encouraged, the nation invested in education, irrigation canals, rural roads and the sector continued to grow year by year. Today many Thai farm lands are mechanised and 90% of the farmers use machinery and agriculture labour is less than 34%.

Currently industrialisation has overtaken agriculture and agriculture contributes only 9.3% to the GDP. The success of the Thai agri business was due to their innovation and adaptability to the market conditions.

Government top-down policies must be evaluated and grass root feedback taken, where bottom to top feedback will clear the farmer problems. Farmer grievances must be addressed, their household indebtedness must be resolved, new methods of farming, high yield seeds and mostly a caring attitude to guide the farmer to achieve objectives.

The Government in collaboration with international donors should undertake Policy Research Studies to be conducted independently by researchers and think tanks. Private research will highlight problems and present findings without fear and be objective. Implementation of such findings must be undertaken without delay.

Government officials’ attitudes must change to work with the private sector. Nominated Government officials must be dedicated to the task, otherwise this will be another exercise that starts with great fanfare but ends with a whimper.

Pilot projects must be started and the learnings shared to other areas over a set period of time. It is never too late to get the farmers galvanised to farm, if we only need the will to resolve issues. Need long-term vision and must start now.

(Sun Lai Yung has worked in USA, Singapore, Afghanistan, and the Middle East. He is currently employed as a consultant, and heads the China Investment Desk at KPMG. He has a Master’s Degree in Economics from Northeastern University Boston. He can be contacted at [email protected].)