Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Tuesday, 23 April 2024 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Unfortunately, the same mysticism and beliefs that Buddha dispelled two and a half millennia ago have crept back into Buddhism. It is true that some of it has cultural, artistic, or sentimental values. But if the human affliction for beliefs and mysticism, or the shortcomings in our sensory apparatus, are used to exploit the innocent and waste valuable resources that could be put into better use, that would be an insult to Dhamma, its author, and purveyors. The preferred outcome of comparing Buddhism and science would be to enable science savvy young generations to relate to Buddha Dhamma and prevent falling prey to mysticism

By Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

A flurry of newspaper articles on Buddhism and science appearing in recent times suggests an apparent interest in seeing the religion from a distinct perspective. However, if the intention of such commentaries is to find affirmation of Buddhist concepts based on science, to gain a deeper understanding of complex phenomena using science, or merely to impress the reader is not clear from these writings.

Western scholars have been on a mission to evaluate the scientific validity of Buddhism for over 150 years. Exploration of this vast literature shows that Buddha Dhamma, does not need any affirmation as it is ahead of modern science. In a world dominated by science, the pragmatic purpose of comparing Buddhism and science is to use the current scientific knowledge to relate or interpret hard to grasp phenomena that are transmitted to us in a language that went extinct hundreds of years ago. And thereby dispel any misconceptions and mysticism surrounding Buddha Dhamma.

The traditionalists insist that science and religions are incompatible, and comparisons are meaningless. They are right; a religion, by definition, is based on a belief system, not amenable to science. However, as Buddhism, which is a religion by any standards, and Dhamma are two different things (see Buddhism vs Dhamma, FT, 15 July 2023), there should be no such obstacle to mixing the latter with science. The goal of this write up is to explore the utility of using science to understand the complex phenomenon of Dukkha which is central to Buddha Dhamma.

According to literature, Prince Siddhartha was well educated in traditional academic disciplines befitting a royal, including the Vedas and Upanishads. Later, he studied the teachings of six other thought leaders who opposed the Brahminic tradition. He was not satisfied with the dualistic nature and the reliance on mysterious or metaphysical entities such as atman, soul, svabhava, Brahma, and gods in the explanation of life and liberation in all religious traditions. He went on his own and discovered the middle way and the principle of Codependent Genesis (paticcasamupada) in repudiation of those existing views.

Another way to describe the goal of Buddha Dhamma is to “see things as they have become” (yathabhutha nanadassana) or understand the nature of the universe and the humans’ place in it, without subscribing to superhuman powers or mysticism (Kalupahana 1992). This is the same goal that science strives to achieve.

Buddhist empiricism is experiential; science depends on experimentation

According to the early Buddhist theory, knowledge depends on perception, inference, and, to a certain extent, pragmatism; therefore, Buddha is considered an empiricist (Jayatileke 1963). The Buddhist empiricism is experiential while science depends on experimentation. The Buddhist theory also emphasises that there are limits to human perception and inference. It is this inherent limitation in understanding the universe that causes human affliction to mysticism. What follows is a scientific exploration of these limitations and their consequences.

The analysis of human psychology forms a major part of Dhamma. Whereas scientific understanding lags the Buddhist theory in some respects as scientific investigation of mind did not begin until the late 19th century. It was considered a metaphysical phenomenon not amenable to science. However, recent scientific findings are in remarkable concordance with Buddhist interpretations. I will discuss what science knows about perception using human vision as an example and compare it with the Buddhist version. However, it should be noted that accurate translation of Pali words used in Dhamma into English can be difficult. For example, Vinnana is translated as consciousness, which is defined as the state of being awake and aware of one’s surroundings. On the other hand, eighty-nine classes of vinnana are described in the Pali canon. However, both Buddhist and scientific descriptions of the process of perception are remarkably similar.

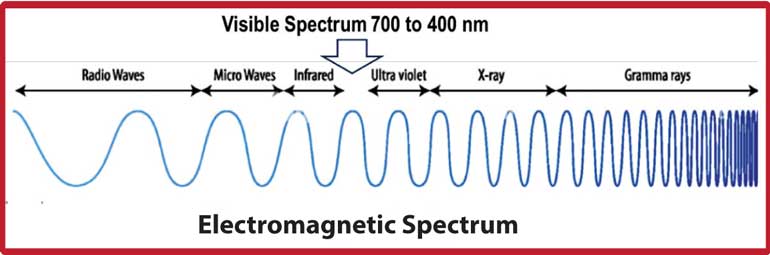

Nobody would argue that a rainbow has colours. It may come as a surprise, but neither the rainbow nor the light that causes that phenomenon has any colours; colour is a mental construct. Electromagnetic radiation consists of waves, and they are characterised by wavelengths, frequencies, and energy, but colour is not among their properties. The human eye is sensitive to about 0.0035% of electromagnetic radiation only, and this fraction, ranging from 380 to 750 nanometers, is referred to as the visible spectrum.

The retina of the human eye has two types of photoreceptors responsible for vision: cone cells and rod cells. There are three types of cone cells that are sensitive to long, medium, and short wavelength light. The rod cells are sensitive to light, darkness, and motion. For example, when sunlight, which consists of the entire spectrum, falls on a rose, except for the radiation ranging from 620 to 750 nm wavelength, all visible light is absorbed by pigments present in the petals. The light that was not absorbed is reflected. When this reflected light reaches the cone cells on the retina of the eye, they undergo chemical changes and generate an electrical signal. This process of sensation is identified as Vedana in Pali.

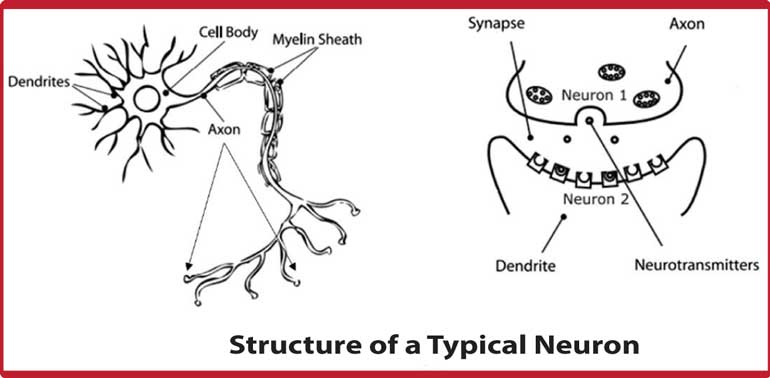

The signal generated is transmitted to the brain through neurons, a special type of cell that makes up the nervous system. The neurons form chains or networks by connecting with each other through structures known as synapses (see illustration). These connections can be opened and closed by changing the chemistry at the junctions, and thereby controlling the flow of the electrical signal. In fact, which is how the signal is processed in the brain. Buddha called the organ (Indiya) that performs these functions the mind (manas), the sixth sense faculty, and the perception of the electrochemical signal form the eye at the brain is called Sanna.

Mental formations

What happens next is complex: first, all the information contained in that signal is saved as a neural map constructed using synaptic connections, akin to a three-dimensional QR code. If this is the first time someone, say a toddler, sees a rose, the signal received from the eye, or the neuronal map formed have no meanings on their own. It is a set of data that is enough to recreate the same sensation in her mind. However, if an adult around her explained to her that it was a “rose” and its colour is “red,” that information received from the auditory signals coming from the ear are also saved as neural maps. The brain constantly scans these maps in the background, just like the autonomous beating of the heart. And this activity enables the brain to collate the information received from all sensory organs and constructs a meaningful mental image: what is seen is a “red rose.” This process of cognising is called Mental Formations (Sankhara). This is the activity that leads to mental processes, or volitions (karma), which precede actions.

Next time when light having 620 to 750 nm wavelength reflected from any object falls on the child’s eyes, and the signal reaches the brain, the brain notes that there is a neural map already saved, containing the same data, and that sensation is named ‘red.’ As a result, the brain re-cognises the new sensation as red, and the child may be able to express her perception verbally using this convention. If the child were not taught that this sensation is called red, the concept of redness would not exist in her mind. In other words, nowhere in this entire process does an actual thing called “red” exist, not in the light or on the rose. The concept of red is a mere mental construct.

The brain sits in a dark sealed chamber with no access to the outside world. Therefore, our perception of the world is a mental construct based on the signals sent to it by the sensory organs. All sensory information is processed by the brain in the same way. As a result, just like there is no colour in light, there is no sound in disturbances of air, no smell in perfumes, or sweetness in sugar. They are all mental constructs. It goes for touch as well. The enormous repulsion between the electrons on the atoms on our fingertips and whatever object we wish to touch, does not let them make contact no matter how hard we try. What we feel is the force of that repulsion. Therefore, we cannot know how something feels to the touch. It is difficult to come to terms with but the entire world as we experience it is a mental construct.

Despite the scepticism among some religious groups, the theory of evolution remains the best explanation of the anatomy and molecular biology of living organisms. According to this theory, our sensory organs are evolved for the sole purpose of survival under changing conditions, but not for understanding the universe. Not only they are unable to see or feel the reality, but they also have major inherent limitations. For example, we cannot see things that are too small or too far and cannot feel electromagnetic radiation outside of the visible range. Even though the skies are filled with all manners of radiation, we would not know their presence without radios, TVs, or infrared cameras.

Science and technology helped overcome limitations of sensory system

Before the scientific revolution, humans attributed unseen things to superpowers: infectious diseases, for example, were considered caused by unhappy spirits, and appeasing them with prayer, offerings, and sacrifices were believed to be the answer. The germ theory changed all that. Science and technology helped us overcome some of the limitations of our sensory system: the microscope, telescope, and spectrometers are some examples. Even with tremendous technological advancements, there are more unknowns about us and the universe. About 95% of the universe is estimated to be made up of dark matter and dark energy, but science does not know much about them.

Science acknowledges that we do not know much, and technological advancement is the way to expand our knowledge. But science does not advocate attributing unknowns to mysticism or superpowers and returning to prayer, rituals, or sacrifices as our ancestors did. Over two and a half millennia ago, Buddha taught the same thing: there is no mysterious entities or superpowers that can save or harm humans, and the human mind can be developed to better understand the nature and the humans’ place in it, or to “see things as they have become.” According to the teaching, seeing that at the highest level is nibbana.

Despite the late start, science is making good inroads to understanding consciousness. What is interesting is that they are discovering that the Buddha was right. For example, one of the problems they have trouble explaining is the “subjective experience.” Buddha had the answer. Buddha explained two more items in the process of human perception: vinnana and nama-rupa. The repository of neural networks representing our experience, or the knowledge base, is referred to as vinnana. It is translated as consciousness, but caution is warranted as the Pali word has broader meanings than the dictionary definition of consciousness.

Perception

The other process has to do with the subject object relationship of perception. All objects that are perceived by the sensory organs and the sensory organs themselves, that are made up of matter, are referred to as Form (rupa). Interestingly, mental objects are also added to this group, and the two together are referred to as Name and Form (Nama-rupa).

Buddha explained that the human personality is nothing more than a collection of these material and mental processes that keep the human conscious, and he called it the Five Clinging Aggregates (Panchupadanakkhandha): Form (Rupa), Sensations (Vedana), Perceptions (Sanna), Mental Formations (Sankhara), and ‘Consciousness’ (Vinnana). Science has analysed these processes down to atomic level and beyond. They are all physio-chemical processes, and there are no mysteries. There are some gaps in our knowledge, especially surrounding consciousness, but our understanding will continue to grow.

Based on this knowledge, it is possible to deduce three features of life: Since these are all processes, they are in a state of constant change, or flux. Buddha had explained this, and he called it anicca. For the same reasons, there cannot be anything permanent, or have any substance associated with life. Any process is dependent on other processes and conditions, and as a result, they are not owned or controlled by an individual or a superpower. Buddha called this property anatta. That gave the answer to the eternal quest for solving the mystery surrounding the self or athman. The declaration by Buddha that the notions of mine, me, and self are also mere mental constructs, was a first in human history. Therefore, according to Dhamma, the subject-object dilemma of modern science is also a mental construct. A difficult concept to accept due to our evolutionary history.

Buddha described a third quality of life: the human condition, or the life itself. All life processes are in flux, and they are beyond control. The sensory apparatus humans have is inadequate to see the real environment which they must inhabit and navigate. That is the reality of life, the human condition. Buddha described this imperfect, uncontrolled, and unsatisfactory condition that humans must deal with as dukkha. Sadly, the Pali word dukkha has been misinterpreted as suffering ever since the Westerners encountered the word in the late 17th century. Legend has that a European who learned Sinhala thought the Pali word means the same as the similar sounding Sinhala word. And that translation has stuck.

This misinterpretation gives the impression that Buddhism is a pessimistic tradition. It is far from the truth, if anything, Buddha teaching is realistic (Rahula 1959). The term dukkha includes all human experiences, ranging from mundane happiness of householders to the supramundane happiness experienced by those who enter higher mental states, dhyana, not just the negative ones. Therefore, giving a negative connotation to life, i.e., dukkha, is meaningless. It is life as we know it, and without it, there would be no life. There are several theories of consciousness, and most of them agree that consciousness exists as a continuum. That is, human consciousness is more advanced than that of animals. Similarly, some humans have more advanced consciousness than the average human. This is a ‘skill’ that can be improved or cultivated by training. In the Forth Noble Truth, Buddha described the way to develop the mind to above normal levels. The premise is that those who have developed the mind will better understand dukkha and be able to skilfully navigate it, leading to a happy and harmonious life.

A short article like this cannot provide an adequate interpretation of Dhamma from a science perspective or help comprehend the complex concepts like anicca, dukkha, and anatta. In fact, if one were to endeavour to digest what was discussed here, by most accounts, which would equate to insight meditation. However, it should be possible to see that just like in science, there is no place or need for mystery or belief in the teaching of Buddha (Kalama sutta). Unfortunately, the same mysticism and beliefs that Buddha dispelled two and a half millennia ago have crept back into Buddhism. It is true that some of it has cultural, artistic, or sentimental values. But if the human affliction for beliefs and mysticism, or the shortcomings in our sensory apparatus, are used to exploit the innocent and waste valuable resources that could be put into better use, that would be an insult to Dhamma, its author, and purveyors. The preferred outcome of comparing Buddhism and science would be to enable science savvy young generations to relate to Buddha Dhamma and prevent falling prey to mysticism.