Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Saturday Feb 21, 2026

Thursday, 23 November 2023 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

By preventing the CBSL from purchasing Government debt except in an emergency and only over a limited transitory period, it reduces the direct control the CBSL has had over interest rates on TBs and Government bonds

|

The Central Bank Act (CBA) was passed with little enthusiasm on 20 July 2023 after a number of challenges to its constitutionality in the month prior to its passage in Parliament. The IMF, apparently at the behest of the US Government1, had made its financial support to the Sri Lankan Government in the form of yet another Extended Fund Facility (EFF), the 17th such arrangement with the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) in the post-World War II era, conditional upon passing of the CBA.

The Central Bank Act (CBA) was passed with little enthusiasm on 20 July 2023 after a number of challenges to its constitutionality in the month prior to its passage in Parliament. The IMF, apparently at the behest of the US Government1, had made its financial support to the Sri Lankan Government in the form of yet another Extended Fund Facility (EFF), the 17th such arrangement with the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) in the post-World War II era, conditional upon passing of the CBA.

Wijewardena (2023) claims that most of the key elements of the CBA were crafted by Dr. N. Weerasinge, the current Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) when he was the Deputy Governor of the CBSL in the Sirisena/Wickremesinghe administration over the period 2015-2019. Although there have been many criticisms of the CBA our particular concern in the first part of this article is that the CBA prevents the CBSL from directly or indirectly purchasing Government securities where these purchases represent either direct or indirect loans to the Government, and that it does so on the basis of flawed economic thinking. We argue that this restriction on the CBSL’s purchase of Government securities will impede the conduct of active fiscal policy by the GOSL, raise trend rates of interest, and causes them to be more volatile.

The rationale provided for preventing the CBSL from purchasing government securities in the CBA is that Sri Lanka’s recent debt default and underlying balance of payments problems are attributable to Government fiscal deficits funded by CBSL money printing, the so-called monetary financing of the budget. The CBA, it is argued, will provide the CBSL with the force of law to resist GOSL demands for monetary financing of the budget. In its 2023 Annual Report on the Sri Lankan economy the CBSL argues that the proposed CBA would limit the monetary financing of the budget deficit by the CBSL ‘thereby strengthening policies targeted at managing inflation and inflation expectations’ (p.32).

In their report on the causes of the debt crisis of the Sri Lankan economy for the UNDP, Athukorale and Wagle (2022) argue that ‘Fiscal dominance of monetary policy has been a problem in Sri Lanka for decades. Bouts of high inflation and long-term loss of competitiveness can be directly linked to Central Bank printing money to accommodate the political objectives of the Treasury.’ (p.23).

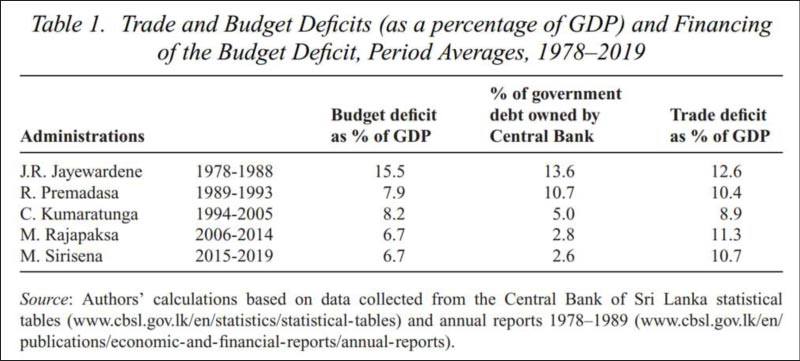

However, the data tell a different story. Table 1, which is taken from Nicholas and Nicholas (2023), compares the external trade balance with the budget deficits and printing of money to finance budget deficits for successive Sri Lankan Governments in the period 1978-2019. It shows that the trade deficit remained stubbornly high over this period in spite of contractions in budget deficits and, more especially, the printing of money to fund these deficits. This not only belies the argument that the source of Sri Lanka’s perennial foreign debt problems has been the running of budget deficits but, more fundamentally, printing money to fund these.

The intellectual origin of the rationale provided for preventing the CBSL from directly or indirectly purchasing Government debt is to be found in the so-called Quantity Theory of Money (QTM). This theory has a long lineage stretching back to the work of David Hume in the 18th century. In its modern incarnation QTM proponents argue that the excessive printing of money by central banks to fund Government budgets result in an excessive quantity of cash being put into the economic system, which in turn results in an excessive expansion in the stock of money in the form of cash and bank deposits held by the public. An excessive stock of money is defined as the quantity of money in excess of the quantity of goods and services in circulation at given money prices.

QTM proponents argue that this results in an increase in the aggregate money price level and a loss of competitiveness of domestically produced goods vis-à-vis those produced in other countries. They see the resulting external imbalances, in turn, requiring countries to incur increasing amounts of foreign currency denominated debts, leading eventually to a foreign currency debt crisis when countries are unable to service these debts.

Central banks target interest rates and not cash base of the system

While the early criticisms of the modern version of the QTM took the form of statistical studies pertaining to the alleged link between, on the one hand, changes in the cash base and the money stock (so-called broad money stock) and, on the other hand, changes in the money stock and nominal GDP (or excess money stock and inflation), more recent criticisms have focused on the policy behaviour of central banks. Of note in this regard is the recognition that central banks target interest rates and not the cash base of the system. When they target interest rates, central banks have to accommodate the demand for cash by commercial banks in a reserve money banking system. This means, contrary to the QTM arguments used to justify the CBA, and in particular its prevention of the CBSL from directly or indirectly purchasing Government debt, it is commercial banks and not the Central Bank that determine the quantity of cash in the system.

That central banks target interest rates and not the cash base (‘reserves’) has been explicitly acknowledged by major central banks of the advanced countries for some time now. In the Bank of England’s 2014 Quarterly Review, McLeay et al. (2014: 15) argue that “Rather than controlling the quantity of reserves, central banks today typically implement monetary policy by setting the price of reserves — that is, interest rates”. In an economics primer for the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis Ihrig et. al. (2021) argue for a wholesale revision of textbook interpretations of the way in which the Fed operates, “focusing on changes in interest rates, not monetary quantities, as the mechanism through which Federal Reserve policies are linked with the banking system and the rest of the economy.”

Notwithstanding its repeated references to the need to control the cash base to curb inflation and restore external balance, the CBSL has for a considerable period of time accepted that its major policy instrument is the rate of interest, or rather various rates of interest. The rates of interest which the CBSL has direct control over are the Standing Deposit and Loan Facilities (SDFR and SLFR), the Repurchase and Reverse Repurchase rates (so-called repo and reverse repo rates), and, until the passage of the CBA, interest rates on Government securities. In its 2022 Annual Report the CBSL argues that the upward adjustment of policy rates ‘helped arrest the further build-up of demand driven inflationary pressures’ (2023, p.23).

While also making repeated references to the importance of controlling the cash base of the system, the IMF too accepts that the major policy instrument utilised by the CBSL is interest rates. Yet, as noted above, both the CBSL and IMF have incorrectly and irresponsibly promoted the CBA as aiding the CBSL in controlling inflation and external imbalances by giving it more control over the cash base of the Sri Lankan economy.

Damaging consequences

There are a number of damaging consequences of preventing the CBSL from directly or indirectly purchasing GOSL debt. One is that in principle it not only limits the ability of the GOSL to use fiscal policy to mitigate the adverse consequences of an external shock to the domestic economy, but will most likely cause it to aggravate the deflationary consequences of such a shock whether or not the GOSL runs a budget deficit to mitigate it. This is because to avoid running a budget deficit when the economy is hit by an external shock the GOSL will most likely have to contract its expenditure (to a level corresponding to the likely reduced level of its revenue), and if it runs a budget deficit to mitigate the impact of the shock in the manner of most other countries it will most likely incur progressively higher interest rates on the debt it issues to finance the budget deficit. Much, of course, depends on the extent to which the CBSL is prepared to purchase government debt, whether in the primary or secondary market, albeit as a ‘short-term transitory provision’ in the context of what can be argued to be ‘an emergency financing need’ in accordance with the CBA2.

A second damaging consequence is ironically that in principle it weakens the ability of the CBSL to exert control over interest rates. Specifically, by preventing the CBSL from purchasing Government debt except in an emergency and only over a limited transitory period, it reduces the direct control the CBSL has had over interest rates on TBs and Government bonds. Perversely, this allows for the possibility of interest rates on Government debt moving in the opposite direction to its policy rates (the SDFR, SDLR and repo rates), exerting pressure on commercial bank interest rates in the opposite direction to that intended by the CBSL when setting its policy rates. This is likely to be particularly problematic when, as in the present situation, the CBSL is trying to lower interest rates in keeping with the fall in inflation while the rates on TBs and Government bonds remain high due to the difficulty faced by the GOSL in reducing the budget deficit.

One only has to witness the repeated pleading with the commercial banks to lower interest rates by the Governor of the CBSL, Dr. Nandalal Weerasinghe3. The problem is that Dr. Weerasinghe has painted himself in a corner. He cannot be seen to be significantly increasing the purchase of Government debt having been one of the principal architects of the CBA that prohibits such purchases except in exceptional circumstances.

A third consequence is that it will most likely cause interest rates in the economy to be higher than they otherwise would be. Preventing the CBSL from purchasing GOSL debt, or limiting this purchase, means that a sizeable budget deficit will exert upward pressure on interest rates on GOSL securities and via these the interest rates in the economy at large. The upward pressure exerted on interest rates pertaining to GOSL securities will be greater than in the past not only because the CBSL is prevented to a greater extent than in the past from purchasing these securities but also because the latter will cause a risk premium to be attached to this debt – a premium that could grow exponentially with the increased issue of this debt at any given point in time.

A risk premium is henceforth attached to Government debt because there is no longer any formal obligation on the CBSL to purchase Government debt. That is to say, there is henceforth the possibility of a default on this debt.

A fourth and related consequence is that it will most likely cause interest rates to become more volatile. This is because it results in the risk premiums attached to GOSL debt changing with changing expectations regarding future levels of Government expenditure and revenue, and the likelihood of the CBSL purchasing this debt as an emergency transitory provision. Since such expectations are likely to be quite volatile, the interest rates they pertain to are also likely to be quite volatile. It is also because monetary policy will henceforth be limited to the manipulation of short term money market interest rates and not also interest rates on Government debt. The exclusive reliance on money market rates, especially repo rates, is likely to result in a greater volatility in these rates, also because they may have to offset countervailing movements in rates on Government debt, especially if the CBSL is reluctant to directly exert influence on these rates.

The preceding is not intended as denying that excessive budget deficits could contribute to inflation and an external trade imbalance. They can, and often do. Rather, it is intended as denying that it is printing money to fund these deficits that is the source of inflation and external trade imbalances. Hence, while there is justification for placing limits on the GOSL running budget deficits in certain circumstances, there is no justification for doing so by preventing the CBSL from purchasing Government debt. In fact, limiting the GOSL running budget deficits in certain circumstances by preventing the CBSL from purchasing Government debt is tantamount to treating an illness by killing the patient.

References:

Athukorale, P. and S. Wagle (2022) The Sovereign Debt Crisis in Sri Lanka: Causes, Policy Response and Prospects. New York: UNDP.

CBSL (2023) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2022. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

IMF (2023) Sri Lanka Country Report. No 23/116. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Ihrig, J. Weinbach, G. and Wolla, S. (2021) ‘Teaching the Linkage Between Banks and the Fed: R.I.P. Money Multiplier’, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis PageOne Economics: Econ Primer, September. https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/page1-econ/2021/09/17/teaching-the-linkage-between-banks-and-the-fed-r-i-p-money-multiplier_SE.pdf

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014) ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 54(1): 14–27.

Nicholas, H. and Nicholas, B. (2023) ‘An Alternative View of Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis’, Development and Change 0(0): 1–22. DOI: 10.1111/dech.12794.

Wijewardena, W.A (2023) ‘New central banking bill: Positive but gaps need to be filled – Part I’ Financial Times, 7th March. https://www.ft.lk/columns/New-central-banking-bill-Positive-but-gaps-need-to-be-filled-Part-I/4-746017.

Footnotes:

1See Wijewardena (2023).

2It warrants noting that the time period for this ‘provision’ was extended from 6 to 18 months in the final stages of the reading of the CBA.

3See for example https://www.dailynews.lk/2023/07/24/local/44317/central-bank-tells-commercial-banks-to-lower-loan-interest-rates/.

(Bram Nicholas is the COO of the research and training company ETIS Lanka.

Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands).)