Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Tuesday Feb 24, 2026

Friday, 5 January 2024 00:30 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The following is our response to the reply of Coomaraswamy, Coorey, and Devarajan (2023), hereafter referred to as CCD, to Nicholas and Nicholas (2023a and 2023b). In this response, we argue the following: First, that CCD’s reply is based on a continued adherence to a theoretical edifice, namely, the traditional quantity theory of money. CCD themselves admit that this theory has no credence with the central banks of the major advanced countries or the academic community. Second, that, CCD’s reply is premised on the belief that demand management policies that have a bearing on macroeconomic phenomena apart from inflation should be the responsibility of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), notwithstanding its lack of formal accountability for the impact of these policies on these phenomena, namely, on economic growth and employment.

The following is our response to the reply of Coomaraswamy, Coorey, and Devarajan (2023), hereafter referred to as CCD, to Nicholas and Nicholas (2023a and 2023b). In this response, we argue the following: First, that CCD’s reply is based on a continued adherence to a theoretical edifice, namely, the traditional quantity theory of money. CCD themselves admit that this theory has no credence with the central banks of the major advanced countries or the academic community. Second, that, CCD’s reply is premised on the belief that demand management policies that have a bearing on macroeconomic phenomena apart from inflation should be the responsibility of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL), notwithstanding its lack of formal accountability for the impact of these policies on these phenomena, namely, on economic growth and employment.

CCD’s justification for an independent CBSL that focuses primarily on inflation

Policy makers and modern scholars provide various justifications for an independent central bank, but the historical impetus for this concept largely arises from the traditional quantity theory of money, which posits a clear dichotomy between real and monetary phenomena. This dichotomy suggests that the factors influencing real economic phenomena, economic growth and employment, are distinct from those affecting monetary phenomena, like inflation and the external balance. Nicholas and Nicholas (2023b) highlight that proponents of this theory argue for an independent central bank primarily focused on controlling inflation by regulating the money supply, with the tacit understanding that such monetary measures do not impact on real economic phenomena.

Despite recognising that central banks predominantly use interest rate adjustments as their main policy instrument and that these adjustments have a bearing on a broader range of macroeconomic phenomena than just inflation, CCD maintain that the rationale for an independent Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) that focuses primarily on inflation as mandated by the Central Bank Act (CBA) is its (the CBSL’s) purpose should be “to serve the public by safeguarding the value of the currency”. The CBSL’s purpose should not be to further the goals of the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL). That is to say, for CCD an unelected group of bureaucrats staffing the central bank of a country know better than the elected representatives of the people of a country what is in the best interests of the latter.

CCD argue that in any case the provisions of the CBA allow for the CBSL to take into consideration the impact of its policies on other macroeconomic phenomena such as growth and employment. They argue,

“…the CBA already requires the CBSL, subject to achieving its inflation objective, to support the Government’s economic policy framework and to pursue the inflation objective in a manner that brings output towards its full employment or “potential” level.”

What CCD fails to address in this regard is the point we made in Nicholas and Nicholas (2023b): although the CBA requires the CBSL to be accountable for meeting inflation targets, it does not hold the CBSL accountable for the impact of its policies on other important macroeconomic phenomena, such as economic growth, employment, income distribution, and poverty. Arguing that the CBA requires the CBSL to consider these other macroeconomic factors when setting interest rates is not the same as holding it accountable for the effects of its policies on these phenomena.

CCD view the independence of central banks in the US, Europe, and Japan as exemplars for Sri Lanka to emulate. However, what is this role model in essence? It is the increasing concentration of economic decision-making power within entities that are not held accountable for their actions. Consider, for example, the recent policies of quantitative easing adopted by the central banks of most advanced countries, following the lead of the US Federal Reserve. These policies have been dubbed the world's greatest financial experiment, a sentiment reflecting their scale and impact. Yet, it was an experiment not subjected to public debate or scrutiny, and one that by many accounts has resulted in the transfer of unprecedented wealth to the wealthy. In an article in the New Statesman of 8 October 2017 entitled ‘How the world’s greatest financial experiment enriched the rich’ C. Thompson quotes Mayer Amschel Rothschild, the founder of the fabulously rich and powerful Rothschild family banking dynasty, as arguing:

“Give me control of a nation’s money and I care not who makes its laws”

CCD’s justification for preventing the CBSL from financing the budget deficit

CCD deny that the justification for the CBA preventing the CBSL from funding the Budget deficit is to control either the cash base of the system and/or broad money stock. They argue,

“there is nothing in the CBA about controlling cash balances for fighting inflation or controlling external balances.”

However, even though there is nothing in the CBA to this effect, this is, and has been, the rationale used by its proponents, including CCD, to justify the prevention of the CBSL from either directly or indirectly financing the GOSL’s budget deficit.

In its 2022 Annual Report on the Sri Lankan economy the CBSL argued that,

“the expected enactment of the proposed Central Bank Act would allow more independence to the Central Bank, limiting monetary financing, and thereby strengthening policies targeted at managing inflation and inflation expectations” (2023, p. 32).

In a similar vein, and notwithstanding their contention that the traditional quantity theory of money positing a link between the quantity of money and inflation has been rejected by most of the central banks of the advanced countries and academia , CCD argue that;

“Between November 2019 and March 2022, the CBSL directly purchased large amounts of government debt, increasing the cash base (or “reserve money”) by a staggering 51%. Among other things, this drove up inflation to a peak of almost 74% in September 2022 and contributed to a precipitous loss of the CBSL’s foreign exchange reserves and a sharp depreciation of the rupee by 80% between end-December 2021 and end-May 2022…”

Indrajith Coomaraswamy, has repeatedly stated that he sees the cause of inflation as an excess quantity of money in the system. For example, in a debate on the merits of an independent central bank at the Colombo University on 17 March 2023 (see Coomaraswamy, 2023) he states:

“If the rate of growth of money supply is greater than the nominal growth of the economy I do not see how this cannot put pressure on prices”

“Supply-side factors have pushed inflation up all over the world but I am not aware of any country that has had over 85%....We have to say that a large part of it is due to monetary expansion due to deficit financing.”

Shanta Devarajan is quoted by Wijewardena (2019) as arguing,

“Governments in most of the countries find easy money available from the central bank to finance their extravagant expenditure programs. Central banks can do so only by printing money. That money finds its way to commercial banks which create more money.”

“The increase in money supply over and above the required amounts will lead to the elevation of inflation.”

What CCD appear to find difficulty in accepting is that most of the central banks and academics who have rejected the traditional quantity theory explanation of inflation see no role for changes in monetary aggregates in the explanation of inflation. Indeed, those rejecting the traditional quantity theory see changes in monetary aggregates as essentially endogenous in the sense that they are brought about by prior changes in inflation and economic growth.

This is not to say that those rejecting the traditional quantity theory do not see fiscal deficits as contributing to inflation in certain contexts. Many of them do. However, for these critics of the quantity theory the resulting inflation is not because these deficits bring about an increase in the money supply when central banks are required to fund them. Rather, it is because they see fiscal deficits, like credit expansion, boosting aggregate demand in excess of aggregate supply.

CCD deny that preventing CBSL from financing the budget deficit has certain adverse economic consequences

CCD deny that the CBA amplifies the deflationary consequences of an external shock

CCD argue that preventing the CBSL from purchasing government debt when the economy is hit by an external shock need not amplify the deflationary consequences of the shock. They give two reasons for this. The first is that the budget deficit that results when the economy is hit by an external shock need not add to aggregate demand and therefore inflation (resulting in higher interest rates) if this deficit is simply compensating for the decline in private demand resulting from the shock. The second is that the CBSL could ease policy rates to prop up aggregate demand and support economic growth provided that this does not conflict with its task of achieving a certain target rate of inflation.

What CCD appear to be ignoring in this regard is that by preventing the CBSL from directly purchasing government debt any and all fiscal imbalances will directly exert upward pressure on interest rates on this debt due to the narrowness of the capital markets in Sri Lanka. Indeed, it is this narrowness of capital markets in developing countries like Sri Lanka that has been used by the IMF and others as the basis for arguing that most developing countries have no option but to borrow from their central banks to finance these deficits.

More fundamentally, CCD appear to ignore the fact that when a developing country with relatively limited reserves is hit by an external shock, such as a global recession, the consequence is likely to be downward pressure on its currency and upward pressure on domestic prices, leaving little, if any, room for monetary policy easing to prop up domestic private demand. In fact, if anything, the policy of inflation targeting would require the central bank of the country that is hit by the shock to raise interest rates in an attempt to stifle domestic demand and prevent the haemorrhaging of foreign exchange reserves in the context of an external shock.

CCD deny that the CBA weakens the control of the CBSL over interest rates

CCD argue that there is no reason to suppose the prevention of the CBSL from directly purchasing government debt weakens its control over interest rates, especially short-term interest rates. They contend that modern central banks, such as the US Fed, exert control over interest rates by means of open market operations designed to influence short-term rates on government debt in secondary markets (i.e., rates on debt of under one year to maturity).

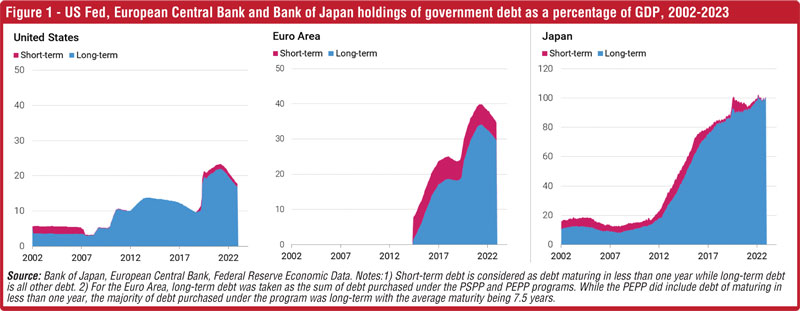

What CCD overlook is that the central banks of advanced countries, such as the Fed, exert control over the whole spectrum of interest rates, not just short-term rates, and they are able to do so because the capital markets in these countries are broad, meaning that there are plenty of buyers of government debt in their primary and secondary markets, and their central banks are able to hold on their balance sheets large quantities of government debt of varying time duration. Indeed, since 2009 the focus of the Fed (like most other central banks of the advanced countries) has been the purchase of long-term government debt with a view to bringing down long-term interest rates (see figure 1).

In contrast, the influence of the CBSL over interest rates is limited because, on the one hand, as noted above, Sri Lanka’s capital markets are narrow, and, on the other hand, the CBA precludes the CBSL holding a significant amount of long term government debt and requires whatever government debt it purchases to be at market determined rates of interest. Specifically, the CBA only permits the CBSL to purchase government securities of maturities under one year and provided that such purchases are at market determined prices and does not exceed one-tenth of the limit of Treasury Bills (TBs) approved by Parliament.

CCD deny the CBA causes interest rates to be higher

CCD deny that preventing the CBSL from directly purchasing government debt or holding on to government debt purchased in the secondary market for any significant length of time causes interest rates to be higher. Indeed, for CCD this prohibition will most likely cause interest rates to be lower, particularly the long-term rate of interest.

CCD’s contention that preventing the CBSL from printing to finance the budget deficit will lower interest rates because it will reduce inflation again stems from their tacit adherence to the quantity theory explanation of inflation, notwithstanding their acceptance of the criticism of this explanation by most central banks in advanced countries and many in academic circles as noted above. CCD could argue that preventing the CBSL from financing the fiscal deficit dampens inflation because it limits the ability of the Government to run a budget deficit. However, as argued above, since it is accepted that the latter also has a bearing on growth, employment, etc., it is a decision that cannot be left to the unelected officials of the CBSL.

Moreover, CCD's argument that inflation movements will more significantly affect long-term rather than short-term interest rates suggests that investors in government debt will anticipate an increase in inflation whenever the Government incurs a budget deficit and consequently escalates its debt sales to finance the shortfall. However, what CCD fail to realise is that it is not the increase in the budget deficit per se that causes interest rates on government debt of all maturities to rise. Instead, it is the requirement for the Government of Sri Lanka (GOSL) to finance this deficit by selling most of its debt in narrow capital markets that triggers the rise. Whether long-term rates increase relative to short-term rates depends on the predominance of the debt maturity used to fund the deficit, whether it is short- or long-term. Given the constraints of the CBA, the likely outcome of an increased budget deficit is a relative uptick in short-term, rather than long-term, interest rates.

CCD deny the CBA causes a risk premium to be attached to government debt

CCD deny that preventing the CBSL from directly purchasing government debt and limiting its indirect purchase will add a risk premium to this debt and make this premium highly volatile. They argue that risk premiums on government debt reflect actual and expected inflation, with the monetisation of fiscal deficits raising the risk premium on government debt because of the risk of default through inflation. They further argue that the risk premium on Sri Lanka’s debt in international markets began its steep rise when taxes were lowered in 2019 and large fiscal deficits were monetised.

The issue with this argument is that it is based on a misunderstanding of the nature and determinants of risk premiums in financial markets. CCD do not acknowledge that risk premiums on debt fluctuate according to the confidence that buyers have in the issuer's ability to honour its financial commitments. If bond investors are concerned about inflation they will demand a correspondingly higher interest rate on all forms of debt, not just on government debt, since inflation erodes the real value of the debt and the interest payments on it. The risk premium that investors will demand for any specific debt depends on their confidence in the issuer's capability to service that debt. Prior to the enactment of the CBA and the subsequent restriction on the CBSL from purchasing government debt, such debt carried a zero risk premium because the CBSL could be relied upon to support government obligations. This is no longer the case and as a result government debt now requires a risk premium, just like any other form of debt. This premium will vary according to investor perceptions of the government's ability to fulfil its debt servicing commitments.

A related point that needs to be addressed is CCD's conflation of domestic and international debt when discussing the risk premium on government debt. While concerns about the future trajectory of inflation may influence the interest rates on domestic debt, they have little, if any, impact on the risk premiums of foreign currency-denominated private commercial debt. For holders of the latter, the issuing country's foreign exchange reserve position is what matters most. Risk premiums on Sri Lankan foreign currency commercial debt began their steep climb when the then-Governor of the Central Bank, Indrajith Coomaraswamy, borrowed over $ 4 billion in late 2019. This borrowing added to the already high level of foreign commercial debt accumulated during his tenure as Governor, raising serious doubts about the country's ability to service this debt.

Concluding remarks

The fundamental issue with CCD's attempt to refute our argument in Nicholas and Nicholas (2023a and 2023b) for the necessity of reforming the CBA by a future Government lies in their persistent commitment to a discredited theoretical framework, the quantity theory of money. This is in spite of their own contention that the theory, and the real-money dichotomy on which it is based, has no longer any credibility in policy-making and academic circles.

Even though CCD acknowledges that the interest rates set by the CBSL in pursuit of an inflation target affect other macroeconomic phenomena such as economic growth, employment, poverty, and income distribution, they maintain that the CBSL should have the freedom to set interest rates with the primary objective of controlling inflation, without being accountable to Parliament or any other entity for potential adverse impacts on these other macroeconomic phenomena.

As we have argued above, CCD insist that inflation results from the monetary financing of the fiscal deficit, hence justifying the prevention of the CBSL from financing it, notwithstanding the fact that it is precisely this relationship that has lost credibility in central banking and academic circles. Specifically, it is the link between central bank holdings of government debt and inflation, as well as the relationship between monetary aggregates and inflation, that is refuted by most central banks in advanced countries and an increasing number of academics.

Reading between the lines of the arguments advanced by CCD, one gets the impression that they are in fact arguing for the demand management of the economy to be transferred wholesale to the CBSL. Specifically, they are tacitly arguing that countercyclical policies seeking to shore up economic growth and employment in the context of an external shock should also be the responsibility of the CBSL. It alone should decide how to manage the trade-off between inflation and other macroeconomic variables such as economic growth, employment, and income distribution, even though formally it is only accountable for meeting inflation targets. As I noted above, the explicit justification given for this by CCD is that the bureaucrats staffing the CBSL know better what is in the interests of the people of Sri Lanka than their elected representatives.

References

CBSL (2023) The Central Bank of Sri Lanka Annual Report 2022. Colombo: Central Bank of Sri Lanka.

Coomaraswamy, I. (2023) ‘CBSL Amendment Act doesn’t give policy autonomy to the Central Bank’, 17 March, Debate on the CBA organised by the Sri Lanka Economics Association in collaboration with the Economics Students’ Association of the Colombo University, at the Colombo University https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0B6n33pGLLU.

Coomaraswamy, I., Coorey, S. and Devarajan, S. (2023) ‘Why the Central Bank Act should not be amended as the Nicholases suggest’, Financial Times, 5 December. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Why-the-Central-Bank-Act-should-not-be-amended-as-the-Nicholases-suggest/4-755926.

Mankiw, G (2019) Macroeconomics, New York: Worth Publishers, 10th edition.

McLeay, M., A. Radia and R. Thomas (2014) ‘Money Creation in the Modern Economy’, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 54(1): 14–27.

Nicholas, H. and Nicholas, B. (2023a) ‘Why the Central Bank Act should be significantly amended by a future Sri Lankan government Part I’, Financial Times, 23 November. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Why-the-Central-Bank-Act-should-be-significantly-amended-by-a-future-Sri-Lankan-government-Part-I/4-755488.

Nicholas, H. and Nicholas, B. (2023b) ‘Why the Central Bank Act should be significantly amended by a future Sri Lankan government Part I’, Financial Times, 28 November. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Why-the-Central-Bank-Act-should-be-significantly-amended-by-a-future-Sri-Lankan-government-Part-II/4-755659.

Senanayake, H (2023) ‘Should the Central Bank Act be amended by a future government?’, Financial Times, 12 December. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Should-the-Central-Bank-Act-be-amended-by-a-future-government/4-756191.

Wijewardena, W.A (2019) ‘Shanta Devarajan: Economist who cannot get disconnected from his motherland’, Financial Times, 19 August. https://www.ft.lk/columns/Shanta-Devarajan-Economist-who-cannot-get-disconnected-from-his-motherland/4-684113.

(Bram Nicholas is ETIS Lanka research and training company COO.)

(Howard Nicholas is a retired associate professor in economics, Institute of Social Studies (The Netherlands))