Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Tuesday, 14 February 2023 00:28 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The beneficiaries of the clientelist state have been the decisive actors in Sri Lankan politics

My first column for 2023 started thus:

My first column for 2023 started thus:

“If 2022 showed us anything, it was that our political class is unable to put the country ahead of party and work together. This is unfortunate, given the massive challenges ahead. This crisis is far from over.

“The poor suffered the most in 2022, inflation and shortages compounding the effects of the pandemic and lockdowns. The effects will be felt this year by those who flourished in the patronage-centric economy that brought us to this sorry pass. They will try their utmost to safeguard their privileges and the country may become difficult to govern.”

I could have got some satisfaction about my forecasting abilities about the beneficiaries of the patronage-centric economy. Instead, what I feel is sadness. Sad for them and sad for the country. Like the country, these people have been living beyond their means, driving leased vehicles fuelled by subsidised diesel on expressways built with inflated Chinese loans. Unknowingly, they have been part of Sri Lanka’s descent to bankruptcy. Perhaps not so unknowingly, they may be part of the reason the descent continues.

The clientelist state

Sri Lanka is best described as a clientelist state, drawing from and building upon the dominant Kandyan feudal culture.

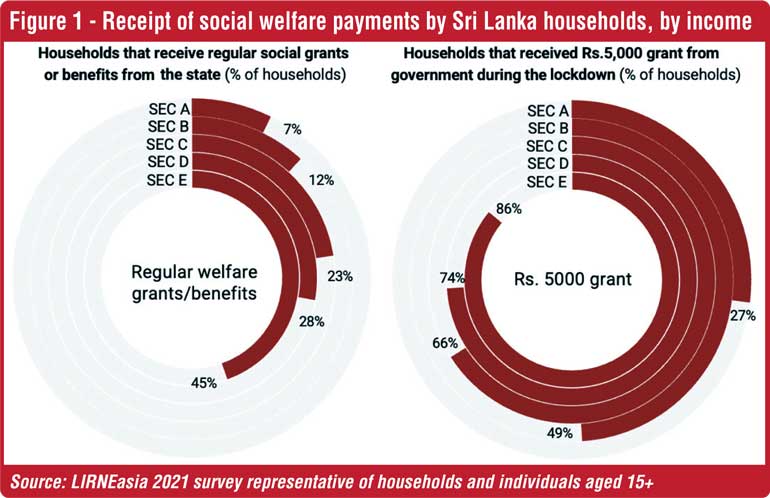

Our democratic veneer is blamed for the state-dependency culture. But in fact, the so-called welfare state serves a group that may be described as the middle class, not the poor. Research conducted by LIRNEasia in 2021 (representative of all households and age 15 and above population in Sri Lanka with a +/- 2.8% margin of error at 95% confidence interval. N = 2,501) showed that a significant proportion of households in the poorest socio-economic classification category, SEC E which is the largest in terms of numbers, do not receive regular social welfare benefits, while some in SEC A (the wealthiest and smallest category) do.

This is an outcome of the rise of the clientelist state in post-independence Sri Lanka, which fits the description of such states in the Britannica Encyclopedia:

“The expansion of interventions by states and local authorities generated new possibilities for politicians to control public resources and, in so doing, mobilise electoral support. Social policies, urban renewal, and subsidies for economic development could all be used to fuel these “political machines.” Be they in the American cities during the first half of the 20th century or in southern regions of Italy after World War II, these machines coordinated clientelistic distribution of collective goods (housing, jobs, subsidies) on a large scale in order to support local “bosses.””

The beneficiaries of the clientelist state have been the decisive actors in Sri Lankan politics. They went with Gota; Gota won. Even the JVP has figured that power is unachievable without their support. As I predicted, their resistance is fierce and focused on changes in the personal income tax (not on the increase in VAT or other indirect taxes). It cannot be proved that this group voted for Gota in 2019 solely because of the tax cuts that he promised and which the country was explicitly warned against by the then Minister of Finance at a press conference and in a memorable tweet in October 2019:

“Gota’s tax plan wants to set #SriLanka on an Express Train to bankruptcy, default and a Greek style debt-crisis. VAT change alone equivalent to Health, Defence or Pensions budgets. #LKA certainly doesn’t need advice from a PR agency conjured ‘business community’.”

This middle layer voted for Gota in the election that came a few weeks after the prescient warning. And when Gota implemented the tax changes weeks after winning the election, none protested about the destruction of the revenue base of the Sri Lankan state. They voted again in August 2020 for the SLPP based on Gota’s destructive manifesto.

When the tax cuts were identified as the trigger that led the economy weakened by perennial twin deficits into bankruptcy the apologists’ response was muted. I recall a Senior Professor of Economics from Colombo weakly responding to my criticism of the cuts on Derana talk show, saying the private sector would not have been able to respond to the challenges of the pandemic if not for the cuts.

But when the 2019 taxes were restored, the resistance was fierce. It appears that the problem is mostly about a debt-fuelled lifestyle that cannot be sustained because of increases in interest in variable-rate loans. But instead of asking lenders to restructure the loans, this group finds it easier to ask the Government to reduce taxes. They have been pandered to by all governments. This is obviously the path of least resistance. Indeed, the Government has already made concessions in the way benefits are taxed.

The auction continues

It is doubtful that the Government can hold the line. After the JVP’s proposal to raise the taxable threshold and cap the tax rate at 24%, comes the principal opposition party’s bid, presented by the former State Minister of Finance who was part of the team that gave Sri Lanka a positive primary balance in 2017 and 2018. Because the spokesperson is silent on capping of the tax rate, the analysis is presented in terms of scenarios, one where the SJB matches the JVP on capping the topmost slab at 24% and the other with the present slabs retained.

The SJB proposal is best understood as a bid at the auction of non-existent resources. The SJB is competing with the JVP for the relatively large number of potential votes of those who would benefit from the raising of the threshold from the present Rs. 100,000 a month. The JVP places its bid at Rs. 200,000 hoping to place Balthazaar in the Mayor’s seat. The SJB counters at Rs. 250,000 to safeguard Rahman’s campaign.

What to do about the JVP’s bid to cap the top tax rate at 24%? The SJB uses the oldest trick in the politician’s book: say nothing, allowing the flexibility to respond if the JVP bid attracts a lot of attention; also allow people like me to give them the benefit of the doubt.

The real questions are whether we continue the auction of non-existent resources at our periodic elections (even when the elections are for local government bodies that have no power whatsoever over taxes)? Will the clientelist state win a Pyrrhic victory, taking all of us down in their effort to safeguard their spoils?