Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 8 May 2020 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka and India can be considered as the only two Asian countries that have chosen and followed the democratic path since independence.

The Indian National Congress which led India’s freedom struggle had a very clear democratic vision from its very beginning. It can be said that the democratic outlook of the Congress had advanced further after Gandhi took over the leadership of the Congress. The Congress appeared strongly for democratic values and played an important role in socialising them. It had a Charter of Human Rights of its own as far back as 1936 when there was no organisation of the United Nations.

In a democratic sense, Sri Lanka’s independent movement did not reach such an advanced stage. Though some leaders of the independent movement of Sri Lanka had been educated in the West, they however, did not have an advanced liberal outlook. All the leaders of the independent movement except A.E. Gunasinha were so backward in their outlook that they opposed the proposal to grant universal suffrage.

From an ideological point of view, despite the leaders of Sri Lanka being so backward compared to their Indian counterparts, the country still chose the path of democracy notwithstanding these limitations and shortcomings.

Sri Lanka faced two military coups d’état and three armed insurrections in the interim, and none of them were able to change the democratic path that Sri Lanka had been pursuing. Both President J.R. Jayewardene and President Mahinda Rajapaksa, who can be considered the two most powerful leaders that emerged in Sri Lanka since independence, attempted to establish a long-term one-party rule, but, in the final analysis, they failed to achieve their dream.

Dictatorial expectations

By the time the last Presidential Election was held, Sri Lanka’s democratic system of governance was not on a stable footing; it was in a state of extreme decay and dilapidation. Numerous factors such as the lack of a strong foundation for democratic polity, failure to maintain the system properly, violation and deformation of the Constitution by ruling parties which came to power from time to time for their power-hungry objectives and converting public administration into a system of plundering public property after 1978 caused this situation.

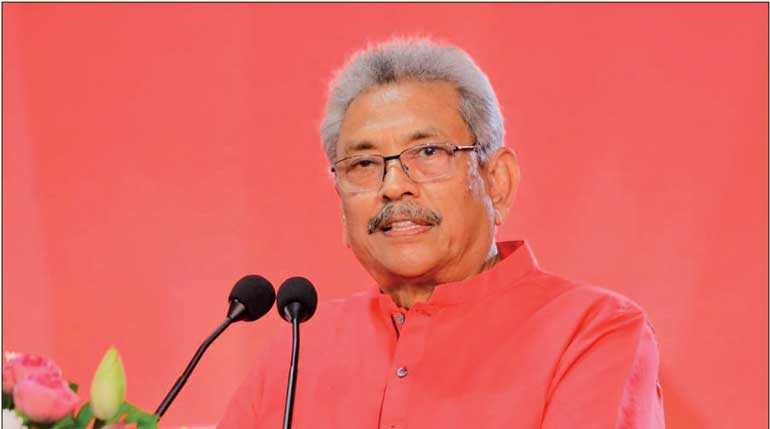

The distortions and degradation of the political system caused a major breakdown in public confidence in democracy. In this undesirable social environment an idea was spreading among the people and was also being spread subtly that the country needed a benevolent dictator, a well-deserving ruler who loves the country. Obviously Gotabaya Rajapaksa was being introduced to the country, both directly and indirectly, as the best person for the purpose.

The successful role he played as the Secretary of Defence in the war against the LTTE and in beautifying Colombo city later, after the war was over, was used to build his political image. There was a strong propaganda campaign in operation for two to three years aimed at preparing the mindset of Sinhala Buddhist majority to ensure the victory of Gotabaya. This campaign was successful in building the image of Gotabaya Rajapaksa as the only hero who could rescue the Sinhala Buddhist people and the country from the grip of Tamils and Muslims.

The knotty 19

To bring Gotabaya to the fore as the presidential candidate at a time when the 19th Amendment had deprived the Executive powers of the president, thereby reducing his status to a level of a nominal head of state, was a significant aspect inherent in the program implemented to bring him to power.

Prior to adopting a presidential system in 1978, Sri Lanka had a parliamentary system of governance based on the British Westminster model. At that time, the president’s position was similar to that of the constitutional monarch of Britain. The real centre of political power rested on the cabinet of ministers headed by the prime minister, elected by the Parliament.

With the adoption of a president-centred Constitution in 1978, the importance of Parliament in State power became secondary, with the president being its main centre. Consequently, the power of Parliament was subordinated to that of the President. Now, 37 years later, with the enactment of the 19th Amendment, the situation has been reversed and the Executive power of State held by the President removed, making him only a nominal head and the cabinet of ministers led by the prime minister being made the main centre of State power.

But this amendment did not venture to change the system of electing the president; and as such, an appropriate methodology to elect the nominal president was not prescribed. Usually, a nominal president is elected either on the recommendation of the prime minister or like in India, by the vote of a limited body exclusively appointed for the purpose.

Strangely, in Sri Lanka, provisions adopted for electing the executive president were not changed despite the 19th Amendment having already deprived him of Executive power. So the same method used for electing the executive president was continued for electing the nominal president as well, i.e. by public vote in a Presidential Election held treating the whole country as a single constituency. Needless to say, this is a serious error.

Law and power

Gotabaya Rajapaksa was able to achieve a remarkable victory in the Presidential Election 2019 on the strength of Sinhala Buddhist votes. Despite the fact that the new President had been elected by a General Election held treating the entire island as a single constituency, unlike his predecessors he doesn’t have Executive power; according to the Constitution he is only a nominal president.

Apparently the majority who voted for the new President were not aware of the changes effected by the 19th Amendment in the powers of the President. They seem to have believed that the new President had the same power possessed and exercised by his predecessors.

If Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the political mechanism that brought him to power had really wanted to gain the control of central power of the State, they should have contested for the post of prime minister on which the 19th Amendment had vested Executive powers rather than contesting for the presidency which is only a nominal post sans Executive powers.

Yet, strangely, not only Gotabaya Rajapaksa, but also the political mechanism that brought him to power were not interested in securing the major post of the central power of the State; instead they were keen on securing the post of president, which is only a nominal position.

It is not clear whether this decision to contest for the presidency was a legal misreading of the power distribution under the 19th Amendment or a deliberate strategic attempt to gradually appropriate supreme power as a sequel to the ascension of office. If the latter is true, it is not a simple error but a serious offence.

What’s the end?

It is quite clear that the coronavirus pandemic has created a situation where a Parliamentary Election cannot be held as required by the Constitution. It is very rarely that extraordinary and unforeseen situations of this nature may arise, which are not prescribed in statutes and cannot be foretold.

In such situations, the Parliament is empowered to make laws and adopt policies necessary to meet the situation. However, the Parliament finds it impossible to intervene in this situation and find a solution as it stands dissolved at the moment and the President has stated unequivocally that he is not in favour of reconvening the Parliament despite having the power to do so.

The President too, is unable to offer a solution to the problem, as he has no legislative power to enact laws. Under the circumstances, it is the responsibility of the Judiciary to offer a solution to the problem which is of great national importance.

The Election Commission had the ability and opportunity to refer the issue to the Judiciary and to find a solution to the crisis. There was also a very clear and important Court decision to guide the Commissioner of Elections on situations of this nature. Yet, the Commission refrained from referring the matter to the Judiciary, informally passing the buck to the President.

The President also did not comply with the request of the Election Commission and refrained from consulting the Judiciary or reconvening the old Parliament. The Opposition parties too were not keen in instituting legal action or consulting the opinion of the Judiciary.

Ultimately, the issue will end at the Judiciary, subjecting the latter’s independence and fairness to a litmus test. Failure to find a legitimate and practical solution acceptable to all will inevitably result in Sri Lanka entering the annals of history as a nation that plunged into a state of anarchy amidst a pandemic.