Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Monday, 25 April 2016 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Source: EconomyNext

Monetary Board is the authority on monetary policy

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has issued a response (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/536676/Central-Bank-responds-to--Dilemma-in-Monetary-Policy--Monetary-Board-caught-in--The-Devil-s-Alternative-?-) to an article which this writer had published in this series (available at http://www.ft.lk/article/534654/Dilemma-in-monetary-policy--Monetary-Board-being-caught-in--The-Devil-s-Alternative-?) earlier.

This writer’s article had questioned the logic and economic rationale of the loose monetary policy being pursued by the Monetary Board at a time when there is a serious economic crisis looming over the nation.

These issues were raised with the Monetary Board because it is the board which has been incorporated and charged under the Monetary Law Act with the responsibility for pursuing suitable policies for the preservation of the domestic and external values of the rupee, the legal tender currency in Sri Lanka. The institution known as the Central Bank has no legal status under the law; it simply functions as the Secretariat to and the operational arm of the Monetary Board to facilitate the latter to adopt and implement suitable policies. Hence, if the policies adopted by the Board do fail, its members, consisting of the Governor, Secretary to Ministry of Finance and three outsiders, have to take responsibility for such failure.

The Central Bank does not have legal responsibility for such failures, though in the eyes of the public it is usually the Central Bank and not the Monetary Board, which is at the receiving end of criticism by all. In this background, it is presumed that the response under reference had had the sanction of the Monetary Board before its issue. The response does not say so, but chooses to refer to the Monetary Board as CBSL, implying that both are synonymous – an inaccurate representation of the board.

Failure of policy by the Monetary Board

Failure of policy by the Monetary Board

This writer’s article had raised several key issues relating to the performance of the Monetary Board in the field of monetary policy and government securities management in the recent past. The arguments which were presented by this writer were as follows.

Sri Lanka is in a serious economic crisis today. It has been even admitted by the Monetary Board in its monthly monetary policy review for March 2016: Growth has decelerated, core-inflation is picking up, foreign reserves have fallen and money and credit have ballooned. On the other side of the spectrum, the Government budget is in serious difficulties. This is a classic example of a macroeconomic imbalance which has to be corrected by increasing interest rates and curtailing the total demand in the economy.

This was the state of the economy pronounced by the board in its monetary policy review. To this writer, it was like a pre-obituary notice because it had documented the symptoms of a dying patient. When a patient is in a critical condition, the board as the physician should give him emergency medical care. The market expected it from the board but what it did was completely the opposite. It had decided to keep the interest rates unchanged expecting the things to become better on their own. This low interest rate policy of the board when the exchange rate was under pressure for depreciation has had several unintended consequences.

Responding to the increased borrowing requirements of the Government, the market had already increased interest rates well above the board’s policy rates. It had given arbitraging profit opportunities for market participants.

Furthermore, the low interest rate policy of the board had worked asymmetrically: it had reduced deposit rates but kept the lending rates at their previous levels. The result has been the opportunity given to commercial banks to make thumping profits in 2015.

In the same way, the manipulation of the primary issue market of government securities has provided another opportunity for market participants to corner the government securities market and make huge profits at the expense of the Government and leading institutional players in the market. This was suggestive of another bond scam, similar to the scam which the country had had in early 2015. The Monetary Board cannot just keep a blind eye on these happenings since they would cause irreversible damages to market confidence as well as to board’s own credibility.

The cherry-picking response of the Monetary Board

But the response issued by the board had made a simple ‘cherry-picking’. Instead of clarifying all the issues, it had just selected a few and attempted to justify its policy stance. The board had said that it had indeed tightened the monetary policy by increasing the Statutory Reserve Ratio or SRR in January 2016. It had alleged that this writer had seemingly been unaware of this policy tightening by the board.

But in actual practice it is the board which has been unaware of the analyses made by independent economists, including this writer, questioning the wisdom of using SRR for policy tightening when it had been proved a dead duck causing unintended consequences. This writer used one full article in this series to question the board’s wisdom on this count (available at http://www.ft.lk/article/515521/Looming-economic-crisis--policy-approaches-are-too-short-and-too-late-while-some-are-unproductive).

Contrary to the belief of the board that SRR is an effective policy tightening move, it has imposed an additional tax on banks, forced them to increase interest rate margins to the detriment of depositors and incentivised them to abandon core banking and move into non-core financial services.

Hence, a Monetary Board with foresight would not dare to resort to SRR unless it is an emergency with no other more effective measures available at its disposal to bring a disorderly market to order.

Micro-prudential measures not monetary policy measures

Micro-prudential measures not monetary policy measures

The Monetary Board in its response has claimed that two micro policy measures introduced by it to attain some other objective are equivalent to ‘tightening of the monetary policy’. One is the imposition of a loan to value ratio of a lesser magnitude so that when vehicle related loans are granted, borrowers have to keep a higher margin as their stake and banks would lend only a smaller percentage. The other is the changes introduced to vehicle import duties making vehicle imports more costly.

Loan to vehicle ratio is not a monetary policy

But the board may inform itself of three issues relating to a measure like the imposition of a stricter loan to value ratio.

First, countries introduce such measures not as a monetary policy but to prevent a bubble being built up in the credit markets leading to distress in financial institutions. The cause of the 2007/08 global financial crisis was the bubble built in the housing market in USA with cheaper and relaxed credit facilities.

When financial institutions lend up to 90% of the vehicle value, prospective vehicle buyers would find it cheaper to own vehicles out of purely borrowed money. Their vehicle-owning ambitions were also facilitated by cheap interest rate policies followed by the Monetary Board. Hence, there is a bubble built up in the vehicle financing markets. However, when borrowers are unable to repay their loans, as was the case in the US housing loan market, the bubble bursts and financial institutions are saddled with a higher ratio of non-performing loans.

Hence, imposition of a stricter loan to value ratio is a micro-prudential financial sector regulatory measure and not a monetary policy measure.

Secondly, the board should in its experience appreciate that vehicle loans are also granted by leasing companies and finance companies which are outside the board’s monetary policy ambit. Hence, if this micro-prudential measure is introduced by the Monetary Board as a monetary policy measure, its efficacy maybe diluted.

Thirdly, the market was well aware that when the Board introduced this measure, the Ministry of Finance unilaterally annulled it creating confusion among market participants. This was an instance where financial policymaking had been appropriated by the Ministry of Finance from the Monetary Board. The market expected a quick clarification from the board about this unsavoury ministerial intrusion into its rights. But the stoic silence it maintained over the affair displayed its total surrender to the ministerial whims.

In the same way, the change in the import duties on motor vehicle imports was not a monetary policy measure but a part of the Government’s fiscal policy measures to raise revenue.

In fact, in 2015, about a third of the Government’s tax revenue had come from import duties on vehicles. It is unfair on the part of the Monetary Board to claim credit for a measure introduced by some other authority for a different purpose.

Declining rupee liquidity is a creation of the Monetary Board

The response issued by the Monetary Board has admitted that the declining rupee liquidity in the market has resulted in most market interest rates ‘increasing substantially’. The cause for the decline in the rupee liquidity was the Monetary Board’s intervention in the foreign exchange market by selling its foreign reserves to defend the exchange rate.

When the board sells dollars in the market, the rupee liquidity gets transferred to the Central Bank and is sterilised within the bank. Then to supply liquidity, the board has to allow financial institutions to use its standing lending facility window at a rate of 8% per annum. This is where the board has erred because it causes an increase in its net domestic assets and a fall in its net foreign assets.

Thus, on one side, it has created the liquidity shortage by selling the dollars it holds. On the other side, it prints new money and permits financial institutions to borrow from the Central Bank at a cheaper rate. This has led to an increase in the market interest rate above board’s policy rates.

Monetary Board is following the market

This development made the board a follower, rather than a leader, with respect to both interest and exchange rates. When this writer pointed this out, it had been totally misunderstood by the board. In the penultimate paragraph of its response, it takes credit for the market interest rate increases due to the market distortions it has created.

When the board follows the market, it loses a powerful monetary policy instrument. In its future policy decisions, it has to continuously increase interest rates and also the exchange rate to match the prevailing market rates. This is like a policeman allowing a thief to have his gun and beg afterward that he should not be shot. The board has thus lost its powers. It has to now be a passive spectator of the events that would unfold in the market.

The bad side of this development is that the board, out of desperation, might resort even to draconian laws for salvage. The reintroduction of the repatriation of export proceeds by exporters last week by the Ministry of Finance, presumably with the board’s concurrence, is one such instance (available at: http://www.sundaytimes.lk/160424/news/move-to-rush-back-export-earnings-191070.html).

A second bond scandal?

The board has failed to respond to two vital issues raised by this writer in the article under reference. One is the arbitraging profit opportunities provided by the board by keeping its policy rates ‘substantially lower than the market rates’. The other is the inconsistent public debt management policy adopted by the board.

When the board cancels all the bids at the primary auctions for government securities, it disseminates information across the market that in the forthcoming auctions, the board would accept a higher volume of funds than the one announced to the market. Then, there is a pressure for bidding at low prices which mean at high interest rates. The board before 2014 prevented such practices by primary dealers by getting EPF to come to the primary market at appropriate yields.

The story circulating in the market today is that EPF is no more in the primary market in an effective way thereby allowing predatory companies to corner the market completely. Two independent analysts have already commented on the Board’s conniving failure on this count (available at: http://www.economynext.com/Sri_Lanka_central_bank_denies_bond_auction_manipulation_as_concerns_rise-3-4802-3.html#.VxwajrGffEM.mailto and http://www.sundaytimes.lk/160424/business-times/too-much-bonding-at-cb-auctions-greater-transparency-urged-190596.html).

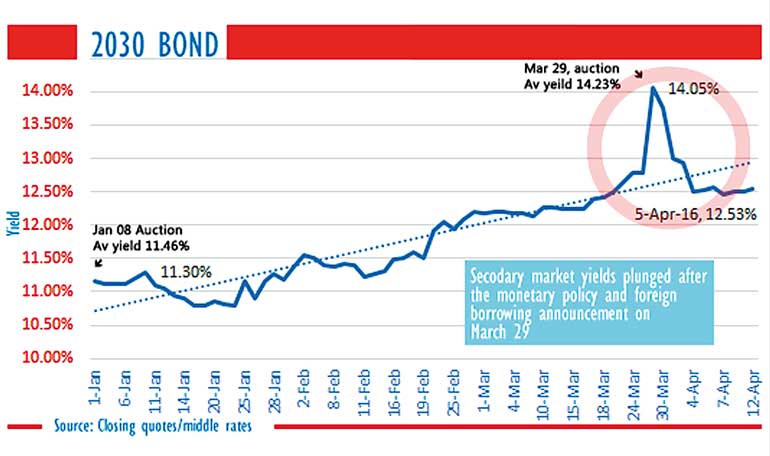

The analyst commenting in EconomyNext has documented the interest rate developments in the Treasury bond market prior to and before the Treasury bond issue in question in late March 2016. The results are shown in Graph 1.

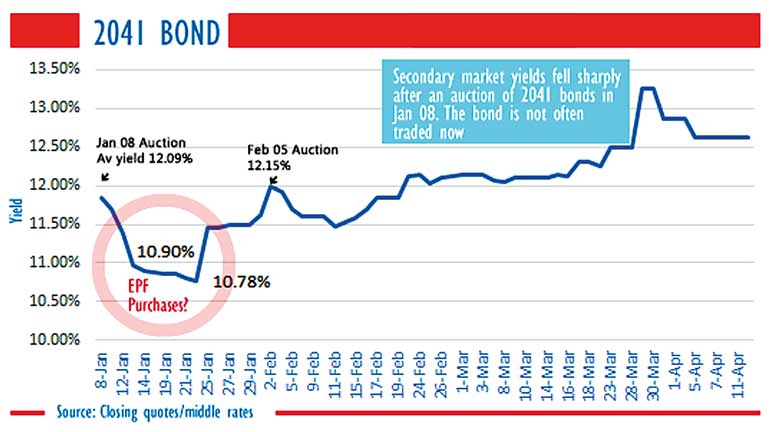

He also has graphically presented how EPF had been manipulated, perhaps without board’s knowledge, to permit some predatory primary dealers to dump their pumped-up bonds on EPF. This is shown in Graph 2.

This story maybe untrue, but since the board does not release full information to the market, such a damaging rumour gets wings to fly across the market gaining credibility at each flutter of wings. Hence, it is in the interest of the board to release full information to the market without waiting for the civil society activists to demand for such information in terms of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution.

The media has already reported one such demand for information (available at: https://www.colombotelegraph.com/index.php/chandra-demands-for-information-on-treasury-bond-issuance/). The whole market is now waiting for the response of the Board.

This writer in the first article under reference has given the details of a potential Treasury bond scam in which it is alleged that a section of primary dealers had unloaded the bonds they had bought at low prices to unsuspecting investors in the institutional sector by deliberately driving the bond yields down. Unfortunately, the cherry-picking response from the board had not dealt with that issue thereby allowing the scandal to rub on its nose.

An EFF facility of $ 1.2 billion not sufficient

The board has expressed confidence that the proposed Extended Fund Facility loan from IMF would help it to build trust among investors in the Sri Lanka rupee. This confidence of the board is only partly correct. That is because a loan of just $ 1.2 billion, released to Sri Lanka in tranches of about $ 300 million each, would be totally inadequate to meet its foreign exchange commitments over the next 12 month period.

According to the data released by the Central Bank, foreign loan repayment commitments alone in the next 12 months will be about $ 4.5 billion. Hence, the IMF facility will just give only a mental complacence to the board without delivering a sufficient quantity of hard dollars to meet the market shortfalls. Such hard dollars have to be acquired by it by borrowing from commercial markets.

The board has lost its credibility in the eyes of the market.

Getting a loan from IMF is not just sufficient for the board to build trusts among market participants. That requires the board as well as the senior officials of the Central Bank to establish unmarred credibility by both the words they utter and the deeds they subsequently commit. The feeling of market participants is that the arrogance displayed by senior officers of the bank in receiving constructive criticism has done much damage to the trust building exercise of the board.

It is common knowledge in the market today that the Central Bank, the operational arm of the board, does not answer calls or clarify the issues raised by market participants. The Monetary Board which finally has to take responsibility cannot keep a blind eye on the acts committed in certain parts of Central Bank’s operations eroding its credibility. Certainly, the Good Governance Government voted to power in 2015 too cannot remain oblivious when another major bond scandal is rubbing against its nose.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])