Friday Feb 13, 2026

Friday Feb 13, 2026

Wednesday, 19 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

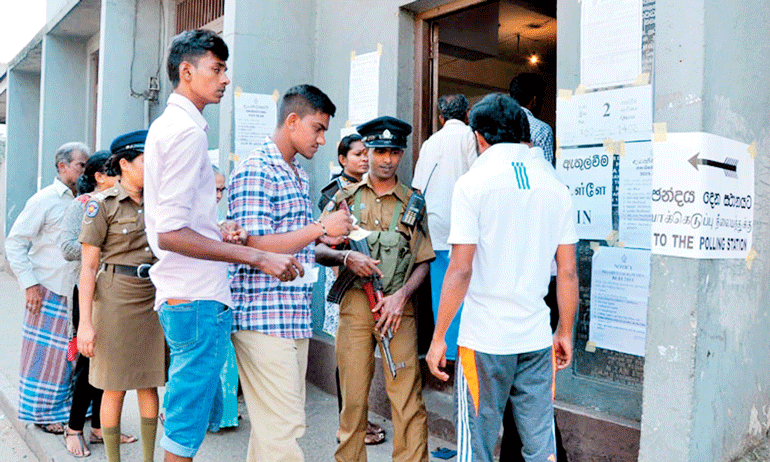

An election is an instance when we see our State apparatus at its best

An election is an instance when we see our State apparatus at its best

The distinction between the state and the government is not always clear. Strictly speaking, the government is made up of elected politicians, and the state apparatus is made up of bureaucrats with more or less tenured appointments. Politicians make laws and policy and bureaucrats implement. A healthy relationship between the two is required for good governance.

The British TV series “Yes, Prime Minister” presents a caricature of a clueless Prime Minister in the clutches of an equally clueless but cunning bureaucracy. Obviously, reality is more complex. What we have seen in Sri Lanka is a slippage of the image of the bureaucrats from larger-than-life figures in the colonial days to kowtowing fools or shameless rogues in recent times.

An election is an instance when we see our State apparatus at its best. The interregnum between the dissolution of Parliament and the returning of new members of Parliament gives the Department of Elections a chance to shine. We were beginning to lose faith even in that process when the previous Election Commissioner famously admitted to immense stress that he underwent during the 2010 presidential election.

The 2015 presidential election was a turning point in that regard, when the new Election Commissioner not only handled the pressures well, but declared that those who break the law deserve not just the stipulated minimum force, but, a gun shot in the head, if needed. Between 27 June and 17 August, with additional powers in his hands, the Election Commissioner and his staff have rallied the police and other personnel to deliver what has been the most peaceful election in our history.

Now that we have seen what our State can do, we need to ask why this performance is not the norm. For that we need to understand how we got to a place where a well-functioning state is seen as a novelty.

Glory days

During colonial times, the revenue agent was the uncrowned King of his jurisdiction. These officials were often young men on their first posting after their education at Oxford or Cambridge.

John D’Oyly, a Cambridge graduate, set sail for Sri Lanka in 1801 at the age of 27. Holding the position of revenue agent in Colombo, Matara and Kandy, respectively, during his tenure, he quickly learned the local language and customs, befriended the Chiefs and engineered the downfall of the King of Kandy in 1815.

A century later, Leonard Woolf received his BA from the University of Oxford and arrived in Sri Lanka in 1904 at age 24 to serve as revenue agent in Jaffna. Woolf is better known for his sympathetic portrayal of the Sinhala peasantry in his 1913 book entitled ‘Village in the Jungle”. HCP Bell was a contemporary of Woolf. He carried out many significant archaeological excavations from 1890 to 1912. The locals who succeeded the expatriates too made their mark. For example, Senarath Paranavithana, Bell’s successor, is still remembered with respect and fondness.

A new generation of bureaucrats rose to prominence after Independence. Many were products of the central school system. Leel Gunasekera who entered civil service in 1957 wrote an acclaimed novel about villagers in Anuradhapura, nearly 50 years after Woolf wrote about Hambantota.

Gunasekera was a part of a cadre of educated civil servants who were sensitive to the constituencies they served. The civil servants or the chiefs of local police stations were often the honoured guests at community events such as the new-year festivals, school sports meets and prize-givings. These officials were treated as the equals or betters of Parliamentarians or local councillors.

But, all was not well. Politicians felt development was impeded by overly powerful and a slow moving bureaucracy.

Overcorrection

When J.R. Jayawardena, then Minister of State, appointed Ananda Tissa de Alwis, an outsider, as the secretary to his ministry. De Alwis helped launch the tourism industry, but this appointment opened the gates of the civil service to political appointments.

The coalition-government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike came into power in 1970 promising, among other things, the establishment of People’s Committees as oversight bodies for State agencies. These committees were discredited, but the idea that politicians can and should interfere with the functioning of the State became entrenched.

The UNP Government of J.R. Jayewardene which assumed power in 1977 introduced the ‘chit’ system, where a letter from an MP was required for a government job. This made the State apparatus a patronage tool and buried any remaining semblance of independence.

Rise of the rogue bureaucrat

The bureaucracy probably reached its nadir in the last five years. After decades of brow-beating, our bureaucracy adapted to the environment and did only what they were told, legal or not. Some filled their own pockets in the process.

The chief accounting officer of a ministry or an agency is its chief bureaucrat, not the minister in charge. Therefore, for every politician accused of stealing there will a bureaucrat who would have complied. We have seen only the tip of iceberg in financial improprieties by politico-bureaucrat duos in the last administration.

Crimes of neglect too are emerging. As the Director General of the Mahaweli Development Authority recently revealed, of the 4,685 farmers settled in Mahaweli schemes in 1976, only 83 have received their deeds to date! It was a simply a matter of typing up the information in a form and placing the required signatures. But, they did not carry out this simple duty causing the farmers hardship and grief. It is noteworthy that Maithripala Sirisena was the Minster in charge of Mahaweli until 2010. Even he could not get the bureaucrats to do their duty.

8 January as a turning point

The postal vote result is like the crack of whips before a procession. The postal-voter base is largely made up of state employees who are on duty on Election Day. On 8 January President Rajapaksa must have realised his fate when he heard the postal vote from Jaffna, largely made up of Army personnel, was 70% in Sirisena’s favour.

In the final result, Sirisena received 51% of the postal votes. This is significant because from 1988 onwards the UNP never received more than 40% of the postal vote, gaining only 20% in the 2010 general election. In the 2015 general election just concluded this week, the UNP received 45% of the postal vote while the UPFA received only 40%.

Future of the public service

Why did public servants decide to cast their votes against a friendly incumbent in the presidential election of January 2015 and then again at the general election of August 2015? Rajapaksa as President doubled the size of public sector to 1.4 million and swore to protect those jobs at any cost, yet the votes of the public sector swung against him in January and stayed that way in August.

Are we seeing a sign of awakening in our State apparatus? Have our public servants finally begun to learn from our Department of Elections about duty and the dignity that comes from a duty well executed?