Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Thursday, 6 August 2015 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In my previous article published in the Daily FT on 8 July, under the title ‘Quality Growth,’ I focused on the need to manage power and energy prudently, and promote entrepreneurship and innovation in order to achieve quality growth. This article deals with a related area which will be indispensable in our push for sustainable growth and this is none other than the promotion of exports.

Sri Lanka’s export goods structure exposes our heavy product dependence. We need to explore ways and means of diversifying our exports and move on to producing export goods and services for which there is a good demand in the international market. For the purpose of this article, I will be focusing on the promotion of manufactured exports, although export of services is also a very important area.

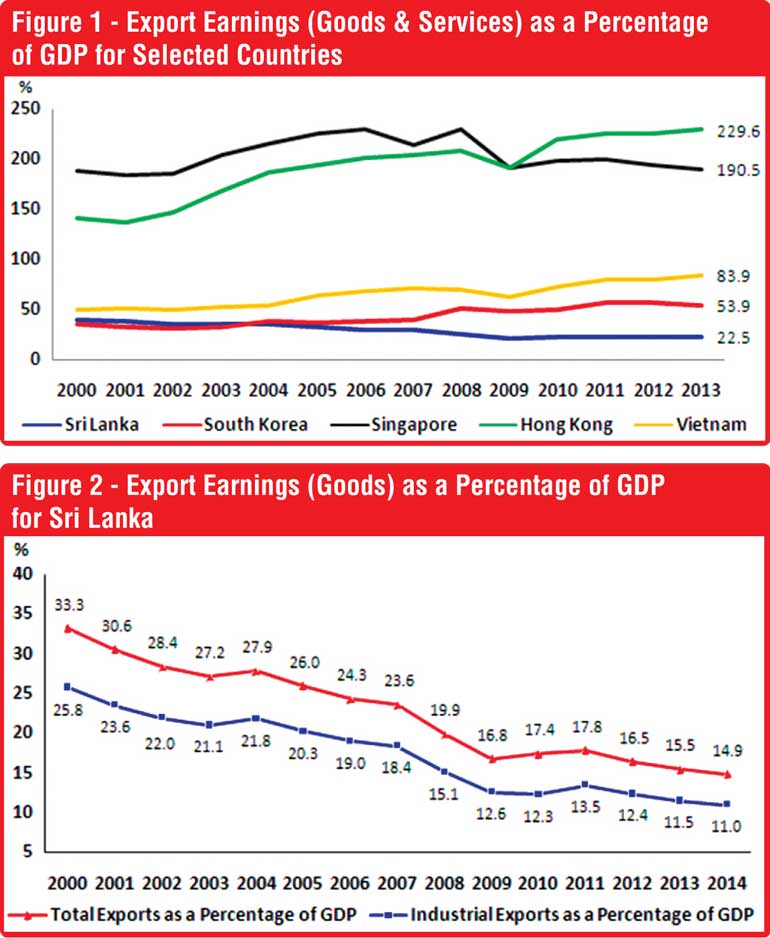

The talk of promoting exports has been going on for a long time. We have heard of the export promotion village scheme, the export promotion decade and various export- earning targets being set from time to time, etcetera. However, what has been the end result? Many other countries that had been behind Sri Lanka in terms of export earnings, have now overtaken us, and forged ahead (Figure-1).

The biggest obstacle that has prevented the country from realising her true export potential has been the lack of resolve on the part of the government to implement a highly focused and consistent export promotion drive, as part of an export-led growth model, while ensuring a conducive macroeconomic and business environment to support that drive. Sri Lanka’s export promotion efforts have been marred by policy inconsistencies and even policy reversals, while the macroeconomic environment too has been mostly unsupportive of such efforts.

By focusing on exports in this manner, I am in no way advocating that we must forget industries that mainly cater to the domestic market. On the contrary, even such industries will stand to gain from an export-oriented economy. This point is further explained below.

Export growth can stimulate economic growth in a variety of ways. A thriving export sector enables economies with narrow domestic markets to overcome size limitations and achieve economies of scale. This is particularly true for Sri Lanka whose population size of only around 21 million is indicative of the small domestic market that we are bestowed with. Additionally, foreign exchange earnings generated through exports are important as a source of funds that can be used to import intermediate goods and capital goods, thereby helping to expand the productive capacity of the economy.

Exports also help to improve economic efficiency through their exposure to foreign competition. Furthermore, export-oriented joint-ventures (foreign and local collaborating ventures) operating in Sri Lanka help to enhance productivity in the country by diffusing their technical knowledge to Sri Lankan partners. In view of these considerations, many countries worldwide had abandoned import substitution (IS) policies in favour of export promotion (EP) policies during the last quarter century.

Diversifying the export products

A primary aim of economic liberalisation strategies adopted in Sri Lanka since 1977 was to diversify the production structure through export-oriented industrialisation, thereby reducing reliance on agriculture-based primary commodity exports. Export-oriented industries, mainly the garment industry, began to thrive swiftly by the late 1970s, after the launch of liberalisation policies and establishment of an Export Processing Zone (EPZ).

This led to a dramatic increase in the share of manufactured exports in total exports, in the post-liberalisation period. However, export-led industries have failed to stimulate the economy due to a lack of dynamism. In contrast, the experience of East Asian countries, which had achieved phenomenal economic growth in the last four decades, has demonstrated the pivotal role that export-led industries can play in fostering growth.

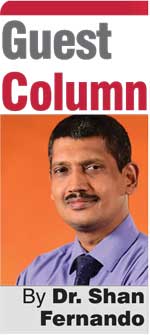

The manufacturing industries in East Asian countries had graduated from labour-intensive products such as textiles and garments, which were dominant in the 1960s to capital-intensive and high value-added industries involving dynamic products such as automobiles, computers and televisions in the 1980s. The trade of these products is growing faster than the world average for all manufactured products. Nearly four decades since trade liberalisation, Sri Lanka’s exports are mostly confined to less dynamic products of yesteryear. Failure to move into a dynamic mix of products has retarded industrial transformation and export growth in Sri Lanka. This situation has led to a continuous decline in export goods earnings as a percentage of GDP, since 2000 as shown in Figure-2. Correspondingly, industrial exports as a percentage of GDP, has also shown a similar declining trend (Figure-2).

However, during the period 2000-2014 there have been signs of a reduction in the heavy dependence on garment exports in the overall composition of export goods. Out of total earnings of export goods of Sri Lanka, textile and garment exports had accounted for 54.2% (69.9% of total industrial export earnings) in 2000. This share had however come down to 44.3% in 2014 (59.7% of total industrial export earnings). Out of total earnings of export goods, the share of industrial exports excluding textile and garment exports, which had recorded 23.3% in 2000 (30.1% of total industrial export earnings), had increased to 29.9% in 2014 (40.3% of total industrial export earnings). This easing of the heavy dependence of earnings of Sri Lankan export goods on just one sector (i.e. textile and garment exports) is a welcome development. Nevertheless, textile and garment exports still account for a high 44.3% of earnings of total export goods. Therefore, the real challenge for Sri Lankan export goods, in terms of product diversification, would be to connect to international supply chain networks and also move onto high-tech exports. Strategies such as production of pharmaceuticals using biotechnology, and the use of nanotechnology for producing a variety of goods ranging from clothing to fertiliser/paints should be actively pursued with a view to upgrading our export goods and pushing them up the value-scale. This is all the more important because empirical studies have shown that annual average growth rates of world industrial exports are higher in the case of hi-tech industries when compared to other manufacturing industries.

Moving up the value-scale through PPP

There are only a very few noteworthy examples of industry-research linkages in Sri Lanka. In this regard the establishment of the Sri Lanka Institute of Nanotechnology (SLINTEC) in 2008 through a public-private partnership, with the purpose of adding value to Sri Lankan products and thereby enhancing their competitiveness in international markets, can be considered as a very good model of such industry-research linkage. This first-of-its-kind initiative has brought together leading private sector firms and key Sri Lankan nanotechnology scientists, resulting in many useful innovations and obtaining of several patents. On another front, in a path-breaking Public Private Partnership (PPP) an MOU has been signed between the Business Management School (BMS) and Industrial Technology Institute (ITI). The MOU is in relation to forming a strategic partnership between the two institutions to further biotechnology in Sri Lanka. BMS, a premier higher learning institution in Sri Lanka, is the Regional Centre of the UK based Northumbria University for Sri Lanka and the Maldives.

ITI is the premier research institution in Sri Lanka functioning under the Ministry of Higher Education and Research. It is credited with several path-breaking research outputs for the development of the country’s industry sector. The collaboration will provide BMS students who are reading for the BSc (Hons) Degree in Biomedical Science/Biotechnology, apprenticeship and training at ITI’s modern laboratory facilities in Colombo as well as in the new complex to be opened in Malabe.

The partnership will also provide research collaboration between the faculty members of BMS and ITI researchers on one hand, and researchers of Northumbria University and ITI researchers on the other, to further knowledge in the key areas. The MOU paves the way for ITI, BMS and Northumbria University (UK) to put their collective brains together to build up a new scientific base for Sri Lanka (Source: Daily FT – 27 July).

The above two examples of Public Private Partnership (PPP) show how creative thinking and the right kind of collaboration can be harnessed to push products up the value-scale, thereby paving the way for hi-tech/higher value-added exports.

Plugging into the fast-growing supply chains

Modern production processes increasingly involve global production sharing. What is meant by global production sharing is the splitting of the production process into discrete activities which are then allocated across countries. By way of an example, the different components of a laptop computer are often produced in many countries due to the vertical specialisation of its production process. This international production fragmentation enables countries to plug into the resulting supply chains as manufacturers/service providers of the fragmented components/activities. The rise of firstly Japan, and then China transformed the prospects and performance of East Asian and Southeast Asian countries. Increased supply chain based trading has been a major part of their success story.

Sri Lanka has an unprecedented opportunity to benefit in a similar way from the accelerated growth in India, by plugging into the fast-growing supply chains of Indian companies and multinationals operating particularly in the Southern sub-region of India (Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu) and by tapping into foreign investment, where necessary.

Conclusion

An export-led growth model offers the best prospects for sustainable growth in a country like Sri Lanka which is bestowed with a small domestic market. Moving up the value-scale by migrating to hi-tech products/exports through public private partnerships (PPP), and plugging into the fast-growing supply chains that are the outcome of international production fragmentation, offer very good avenues for the country to achieve export dynamism which is integral for export-led growth.

(The writer counts over two decades of experience in economic research in the private sector. He has earned a Bachelor’s degree in Economics, an MA in Economics and a PhD in Economics at the Department of Economics of the University of Colombo. He can be reached at [email protected].)