Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Sunday Feb 15, 2026

Wednesday, 16 November 2016 00:08 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The education component of Budget 2017 has many positive features. Unspecified infrastructure expenditures from the previous budget have been removed. The new proposals, except for the free tabs proposal, are mostly well-targeted. The higher education spending proposals in particular show multiple approaches to increase higher education opportunities, while not shirking the Government’s responsibilities.

The school education budget is the focus of this column. The school education budget for 2016 was an ambitious one. The allocation for 2016 quadrupled to Rs. 168.5 billion from Rs. 43.6 billion for 2015. There was excitement then that the Government was committed to education and heeding the battle cry of university teachers that the amount the Government expenditure on education should be 6% of the GDP. In hindsight it was a doomed initiative from the beginning. Nobody questioned the wisdom of 6% and the Government added more money to the line item and did some strange math to meet these unexamined requirements. The center-periphery problem of a monolithic ministry trying to reach out to 9,000+ schools is another issue that spelled failure.

The school education budget is the focus of this column. The school education budget for 2016 was an ambitious one. The allocation for 2016 quadrupled to Rs. 168.5 billion from Rs. 43.6 billion for 2015. There was excitement then that the Government was committed to education and heeding the battle cry of university teachers that the amount the Government expenditure on education should be 6% of the GDP. In hindsight it was a doomed initiative from the beginning. Nobody questioned the wisdom of 6% and the Government added more money to the line item and did some strange math to meet these unexamined requirements. The center-periphery problem of a monolithic ministry trying to reach out to 9,000+ schools is another issue that spelled failure.

However, the reaction of the media, the activists and the public was kneejerk. More spending is good. Let’s celebrate was the response. Nobody had time for deeper questions such as how is the Ministry going to implement this? What is the expected outcome? How will it be achieved? How will we know whether it has been achieved, etc.?

Come Budget 2017, we see the same kneejerk reactions to education spending. There was widespread dismay in social media circles that education spending has been reduced from 2016. Nobody bothered to read the fine print which explained that the by the third quarter the Ministry of Education has not been able to spend a quarter of the amount allocated.

As the Finance Minister explains in Paragraph 88 of the Budget speech, “[W]e allocated in 2016, almost 3 times that of the allocations made in 2014. However, the Ministry of Education has been able to utilize only around Rs. 38,850 million at the end of the 3rd quarter of 2016. We took careful stock of the situation and therefore allocated almost Rs. 90,000 million for 2017. While I admit that allocation for 2017 is less than that of 2016, it is nevertheless 70 percent more than that of 2014. I will also be proposing the provision of an additional allocation of Rs. 17,480 million to further strengthen the development in the education sector.”

Nobody can be blamed for not following four hours of a monotony which we call a Budget speech, but Budget commentators should have read the pertinent paragraphs before protesting. They should have asked about the impediments to spending and whether those have been removed, etc., the more important questions.

A digital focus is evident in education spending for 2017

It takes a while to understand the Sri Lankan Budget. Allocation for each ministry head is given in the appropriation bill. An annex in the Budget speech lists a set of expenditures on programs separately. For 2017, the total of such expenditures is Rs. 140 billion for some 60 plus items. This amount is about 5% of the total budget of Rs. 2,700 billion but after paying for the upkeep of ministries and a multitude of agencies, this is probably where the Government gets some discretion in spending.

A comparison between the distribution of items in education expenditure proposals in 2015 and 2016 is revealing.

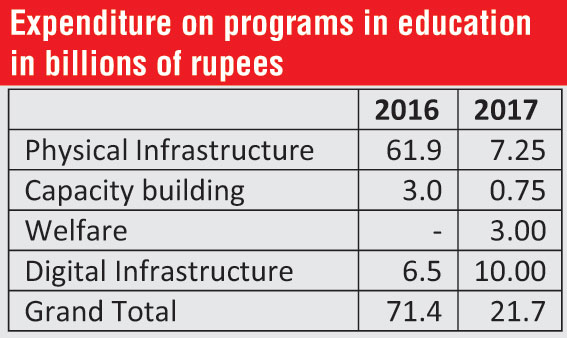

For 2016, almost Rs. 62 billion was targeted for classrooms, labs, sanitary facilities and other physical infrastructure but the amount is reduced to Rs. 7.25 billion in 2017, a more achievable target presumably.

This is a step in the right direction. Mahindodaya Labs by the previous Government were built with one single design for 1,000 or so schools across the country. The labs got built but to what effect we don’t know. There is no formal evaluation but I personally have seen labs unused several years after completion with procured computers almost obsolete.

In implementing development projects, the ministry needs to find a middle ground between efficiency of centrally controlled procurements and effectiveness of local control.

Expenditures for capacity building through teacher training are to be carried over from 2016 to 2017, but new initiatives are proposed at Rs. 750 million for management training for administrators, presumably to learn how to spend money better.

The new welfare initiatives for Rs. 3 billion include monthly grants of Rs. 2,500 for 1,000 gifted students and another similar grant for disable students. These are targeted and needed initiatives. A health insurance scheme is offered for all students at a cost of Rs. 2.7 billion. This is an initiative with the possibility of much value addition later and needs to be watched with interest.

The largest allocation of Rs. 10 billion is for digital initiatives. An attempt is made to rectify the previous practice of putting PCs in schools without a support structure by allocating Rs. 5 billion for renting computers. That too is a new idea worth watching. However, the idea of distributing free tabs for A/L students and their teachers is a disturbing one. Where did that come from?

Where is the action plan??

A search for ‘digital classroom’ on ICTA.lk produces only two results. The first says ICTA aims to “provide appropriate infrastructure and solutions to facilitate the seamless delivery of digital education and strengthen education for sustainable development,” a boilerplate statement.

A second entry is more interesting in that it has a request for proposals for an ICT use survey of schools and for developing a digital classroom strategy. With a concrete proposal to distribute free Tabs included in the Budget already, it looks like the cart has come before the horse.

The Finance Ministry too does not seem to have asked the right questions when they added the line item into the Budget. As the Finance Minister states: “Honourable Speaker, we must create the enabling environment for our students to be able to acquire knowledge easily. We must give them a ‘Smart Classroom’ for which we have already allocated Rs. 6,500 million. To supplement this venture, we will also provide free Tabs for almost 175,000 students who enter the Advanced Level (AL) classes and around 28,000 A/L teachers from 2017. I propose to allocate Rs. 5,000 million for this project. I invite the telecom service providers to support this initiative by providing Wi-Fi connections.”

What kind of knowledge? How will it be acquired? The Minister should have requested more details before allocating Rs. 5 billion for the purpose.

Digital classroom or digital youth?

The digital classroom, unless defined more broadly, is about using technology in the classroom. Mobile devices can enable learning outside the classroom too. Putting mobile devices in the hands of 16-18-year-olds is a new concept which should be more correctly called digital youth, unless the initiative is linked to the curriculum.

Has the Government thought through the outcomes of distributing tabs free of charge? First, is there sufficient education content for these tabs? Grade 12-13 in our school systems is a time when teachers struggle to ‘cover’ a heavy curriculum and students invariably seek help outside. Does the Ministry have content which can compete with what tuition masters provide?

If the aim is technology savvy youth who are able to seek information on their own, even if access is limited to Facebook and other social media, then it is a different story. What are the various ways a 16-18-year-old can use mobile device? Parents are wary of giving phones to youth. How would they feel about Tabs with internet access? If internet access is forbidden by parents or is not available at home, will we have too many freebies lying around while the public is stuck with the cost? The Parliament and the public deserve answers to these questions.

Why tabs?

A young entrepreneur who makes a living by providing IT and English training to rural youth said he bought a Kindle for Rs. 9000 and is testing that for acceptance by youth attending his classes. He is planning to test the Kindle as part of an English language program that he is providing.

He also finds laptops to be more useful than tabs for achieving learning objectives. He is also worried about cheap tabs. The designers of the free Tabs program may have experience of youth in their lives using iPads. Cheap tabs are a different story. Rs 5 billion for 200,000 students and their teachers roughly works out to Rs. 25,000 per student for the unspecified use of a cheap tablet. Is this good use of public money?

What do the research and experience tell us?

The literature on digital classrooms is very clear that the acceptance and use of technology by teachers is essential to the success of digital devices in classrooms. Our own systematic survey of the literature shows that given sufficient tech support and if teachers are convinced of the utility of the technology, they will use technology in the classroom. Digital Bangldesh’s initiative on multimedia projectors for classrooms is an initiative which has shown success.

According to the 2014 OECD report on ICT in the classroom, even with generous support from the Government to train teachers and provide the technology, the use of technology in the classroom is limited in those countries. Also, technology investments are not directly correlated with learning outcomes and neither is technology use. For example, education achievements begin to go down if students use the Internet for more than 1-2 hours in school or outside of school.

The Government’s free tabs thrust is aimed at youth aged 16-18, most likely using tabs outside of the class. I am yet to uncover research on the topic and the ICTA has great responsibility in doing some exploring before action can be taken.

Digital strategy has to be in place before doling out freebies

ICTS has done the right thing by seeking a baseline study and developing a strategy based on that as per their announcement last month. The better strategy would be to use the 2017 Budget allocation to try out several approaches, look for ways to allow more choice for youth and parents and schools, see how tabs or other devices are used and then develop a strategy. It would be gross negligence on the part of the Government to distribute devices without knowing the expected mode of use or the intended outcome.

Vouchers for ICT devices as prizes for various extracurricular competitions

Dumping technology as freebies is the easiest way out. Following up on the success of vouchers for school uniforms, ICTA should expand the choice of devices for youth, by giving them vouchers for purchase of a device of their choice.

Furthermore, instead of a freebie, youth should be given the opportunity win vouchers for their competencies that indicate readiness for responsible and creative ICT use.

In fact, why not award 1,000 vouchers, say, for each province for students selected from a competition on creativity or some other attribute/s that educators wish to cultivate but have difficulty in doing so under the current exam-intensive system.

Let the winning students decide which device they want to purchase. They can decide on a kindle, smartphones, a laptop for some top-up money or other. Next ICTA should follow up on these students to study their preferences and see how they use their device of choice. Integration technology is not flash in the pan activity. It takes patience and creativity to find the right approach.