Friday Feb 27, 2026

Friday Feb 27, 2026

Wednesday, 17 August 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

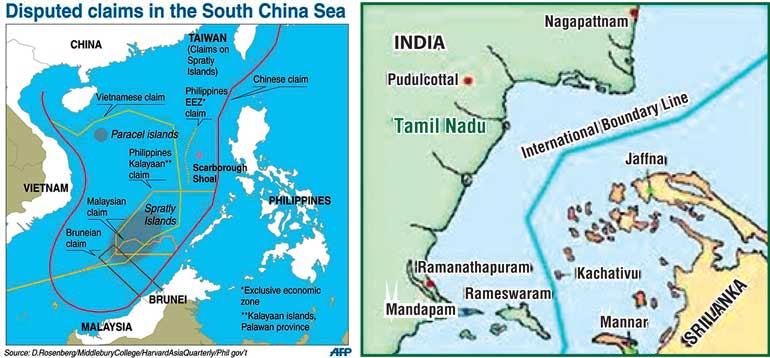

The much awaited verdict of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), which functions as a ‘special arbitral tribunal’ pursuant to Article 287 (3) of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and its Annex VII was pronounced on 12 July, 2016 in favour of Philippines. Although, the Peoples’ Republic of China abstained from the proceedings by refusing to recognise the case, the provisions of Article 287 (3) has given the mandate for the PCA to proceed until a decision is delivered. This has not only denied China’s entitlements under the ‘nine dash line’ drawn around the Spratly islands that sought an area generating an Exclusive  Economic Zone but also aroused its attention on several key points including historic rights and the nine-dash-line claimed by China; land reclamation and construction of artificial island; interference with Philippine’s rights in exploration of fishing and petroleum resources; as well as damage to marine environment. Whatever the outcome that has brought into being in this dispute, it is interesting to note the ‘relevance of historic means’, which was highly debated, with the one at hand between Sri Lanka and India.

Economic Zone but also aroused its attention on several key points including historic rights and the nine-dash-line claimed by China; land reclamation and construction of artificial island; interference with Philippine’s rights in exploration of fishing and petroleum resources; as well as damage to marine environment. Whatever the outcome that has brought into being in this dispute, it is interesting to note the ‘relevance of historic means’, which was highly debated, with the one at hand between Sri Lanka and India.

Unlike the case between China and Philippines, the maritime boundary between Sri Lanka and India in the so-called ‘historic waters’ is a settled law. By virtue of the Agreement entered between the two countries in 1974 regarding the boundary in historic waters between the two countries and related issues, the delimitation process has taken place on grounds of fairness and equity more than the application of the principle of ‘equidistance’ though the final outcome justified the latter. Article 1 of it clearly point out to the fact that the points between the Adam’s Bridge and Pork Strait have been well defined and founded in agreement between the two States thus vesting upon each of them; the ‘sovereignty and exclusive jurisdiction and control over the waters, the islands, the continental shelf and subsoil thereof, falling on its own side of the aforesaid boundary’ in accordance with Article 4.

Sovereignty and jurisdiction over the islands

While most of the islands out of around 19 in the Northern Peninsula including some famous ones such as Delft and Nainativu that has Dutch and Buddhist influence respectively been allocated to the due sovereignty of Sri Lanka; the much disputed island of Kachchativu has been vested upon the sovereignty of Sri Lanka subject however to the enjoyment of access by Indian fishermen and pilgrims without any requirement of visa or travel document as is evidence by Article 5. Granting of such an entitlement does not in any way allow the occupation nor exploration except to the fact that it can only be used as a ‘transit point’ in this uninhabited island located between 9°23’16’N and 79°31’37’E. The advantage for Kachchativu is that it is considered as an uninhabited island that does not itself generate its own maritime zones such as a territorial sea in this archipelago off the northern peninsula in contrast to the Chinese claim in the South China Sea dispute where the Chinese military presence in using Spratly island as a base though artificially constructed over the years.

However, much of the controversy that surrounds the political pressure by the South Indian Government in claiming ownership to this island has triggered over the past few years citing India’s sovereignty over it may have been on the basis of Article 5, but the purported claim is found to have no basis over a settled law as aforesaid. Furthermore, the Maritime Zones Law No. 22 of 1976 has incorporated these provisions in the national law wherein it is bestowed upon the President of Sri Lanka to proclaim the limits of historic waters between the two countries by virtue of section 9 of the said written law. Accordingly, the Republic of Sri Lanka becomes entitled to exercise sovereignty, exclusive jurisdiction and control in and over the historic waters, as well as in and over the islands. Considering all these legal circumstances, it is possible to arrive at the decision that Sri Lanka has acquired the necessary legal and legitimate entitlement to its well defined territorial sea which shall not in any way subject to the opposite claims of India.

Historic waters

Although, Section 9 evidently uses a regime called ‘historic waters’ the law doesn’t specifically provides for any clear cut definition on this phrase. Obviously, the intentions of the negotiators that led to the conclusion of the 1974 Agreement quite possibly may have been the reasons associated between these two countries for over 4,000 years where this sea area was used as a passage for movements from the epic of Ramayana to traceable history of the arrival of Prince Vijaya to Mahathittha in 543 BC, and then the much recent flows of various Indian settlers. However, a legal recognition of a historic character would certainly need a customary rule that creates a fundamental rule in international law from which no derogation is ever permitted called, ‘jus cogen’. The doctrine of historic waters was developed from that of historic bays, which had emerged during the 19th century for the protection of large bays closely linked to the surrounding land area and traditionally considered by claiming States as part of their national territory. Although this statement may constitute the legal necessity in framing the argument on historic waters in modern context, the already existed scenario in the relationships between Sri Lanka and India suggest a much broader view in upholding their mutual entitlement to the adjacent waters. Furthermore, no proper definition is thus provided by either the UNCLOS or the customary law such as the Territorial Sea Convention 1958. Nevertheless, both these conventional and the customary law so mentioned have recognised the legitimacy of any bilateral approaches in proclaiming historic waters. In wake of the absence or failure on the part of international law makers in defining the term ‘historic waters’, except the upholding of special circumstances of such nature in Article 15 of UNCLOS; there exists of a general perception as to the main requirements in setting up a historic waters regime. These include; (1) exclusive use of authority by the State concerned; (2) long usage or passage; and (3) acquiescence of foreign States.

Interestingly, the two States have agreed in view of the 1976 Agreement to respect rights of navigation through their territorial sea and exclusive economic zone in accordance with its laws and regulations and the rules of international law by the entering into of Article V(3). It transpires the fact that these historic waters that have a narrow strip of sea with the narrowest being around 18 nautical miles being equally distributed among the two opposite States by virtue of the 1974 and 1976 Agreements not only grant such rights of navigation but also impose reciprocal duties towards each of them. As a matter of law, the said international law in particular expects countries to perform their due obligations in good faith under the principle of pacta sund servanda improvised by Article 26 of the Vienna Convention on Law of the Treaties 1969 though there will exist no direct implication on the said agreements. But however, in light of both these said agreements lacking any inference as to such a cardinal principle as pacta sund servanda, their respective obligations towards the UNCLOS’s Article 300 would put both two States on track to maintain good faith and prevent from any abuse of rights.

Breach of the rules and encroachment of the other’s maritime zone: the solution been penal or diplomatic?

Issues relating to encroachment of Indian fishermen to Sri Lankan waters should not only be viewed in a much social angle, as the case has a much historic character in nature; but in a more commercial view than political. The recent incidents that took place in Sri Lanka in relation to several thought provoking disputes at both locally and internationally, there arise questions whether those can be properly based within the doctrine of ‘right of innocent passage’ or merely ‘an illegal affair with a commercial intent’. Furthermore, Article 19.2(i) of the UNCLOS makes proviso for any ‘fishing activities’ by foreign vessels to be regarded as an act of prejudice towards peace, good order or security of the coast State thereby confirming that such passage is not innocent. Although, the practice of traditional fishing that survived for many decades or rather centuries between Sri Lankan and Indian fishermen in the region being a noteworthy factor in this regard, the present scenario has overwhelmingly taken over by commercial fishermen. The Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Act No. 2 of 1996 make proviso by its section 6 of Part II that ‘no person shall engage in…, any prescribed fishing operations in Sri Lankan Waters except under the authority and…, of a license issued’ by the Director of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Any entering of Indian fishing vessels can only be allowed on grounds of ‘distress or force majeure’ as per Article 18.2 of UNCLOS in line with the international obligation of coastal States within the meaning of a possible ‘stoppage and anchoring’. It is only by general inference that Sri Lanka can argue on its entitlement as aforesaid, since, the Maritime Zones Law does not refer to y ‘stoppage and anchoring at times of distress and force majeure’.

n the decision of PCA regarding South China Sea, it is held that China had violated among other things; the sovereign rights in its exclusive economic zone by interfering with Philippine fishing, and also failing to prevent Chinese fishermen from fishing in the zone. If we apply the same determination notwithstanding any technical objections raised by China in this said arbitration, it is obvious that any intrusion into someone else’s territory is not a welcoming act recognised by the international law. According to the latest statistics, not only Sri Lanka is affected by this encroachment but also the other countries of the sub-region such as Pakistan and Bangladesh. Indian authorities have alleged that the fishermen of Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Diu, Daman, and West Bengal are continuously affected by the navies of Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, but the sad point is that all these countries including India being Member States of UNCLOS have failed to take appropriate efforts to implement the international law despite they continue to arrest or shoot each other’s fishermen and confiscate their properties at sea. Since, it is the duty and responsibility of the Governments to protect and safeguard the interests of its people and of their countries; the solution is at an arm’s length to resort to the peaceful means of dispute resolution introduced by Article 279 of UNLCOS. If in case it fails, Article 281 allows parties to the dispute to resort to any other mode agreed between them such as by way of bilateral agreement or by conciliation. In such context, the countries are at liberty to resolve the dispute through diplomatic means, and to rely upon the compulsory means of resolution such as the one resorted by Philippines in the South China Sea dispute. Article 287 has provided a wide range of choices in addition to the methods introduced under ‘peaceful means’ of resolution of the UN Charter thus disallowing States to run into hostilities by applying their own respective penal provisions against foreigners and foreign properties at sea.

(Dr. Gunasekera is an Attorney-at-Law who has obtained Master of Laws in International Law with specialisation in Law of the Sea from University of Utrecht, The Netherlands, and a PhD in Maritime Law from University of Hamburg, Germany. He was also a scholar of Int’l Max Planck Research School for Maritime Affairs, Germany and Dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, CINEC Maritime Campus. He is also a visiting lecturer of University of Colombo, Department of Economics in Marine Regulations and Standards and in International Trade)