Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Sunday Feb 22, 2026

Tuesday, 3 November 2015 00:23 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Sri Lanka today is considered a more closed economy than it was in 1970s. Since the turn of the century (2000-2014) its trade (exports plus imports) to GDP ratio has steadily declined from 77% to 41% of GDP. The taxes on foreign trade has significantly increased during the last decade. High taxes negatively affect productivity, innovation, investment, exports, consumer prices and consumer choice. The economic merits of bringing down taxes on foreign trade is clear.

This article shows in Sri Lanka, however, reducing trade taxes can be challenging due to the negative impact it can have on trade deficit, government revenue and domestic industry. It points out how a gradual phase out of foreign trade taxes can reduce this impact and highlights the importance of foreign exchange rate policy of the government in cushioning the impact.

Unreasonably high trade taxes have negative economic outcomes

Sri Lanka has a fairly simple import tariff regime of four bands (i.e. zero, 7.5%, 15% and 25%). Roughly about 20% of products (at 4-digit level) mainly consisting of agricultural and final consumer products are subject to the maximum tariff of 25%. In addition to the import tariff, a host of additional taxes are imposed on foreign trade such as Cess, Special Commodity Levy (SCL) and Port and Airport Levy (PAL) making total tax on imports to be significantly high.

A significant anomaly introduced to trade as of recent has been a tax known as “Cess” on imports. The number of Cess tax bands  are double that of import tariff bands. If the Cess on per unit of imports are added, the number of Cess tax bands can easily exceed fifteen. A considerable portion of imports into the country (especially final consumer products) are taxed both at maximum import duty of 25% and maximum import Cess of 30-35%. In addition, these products are also subject to PAL at 5%. This brings total import taxes on these products to 60-65% of landed value.

are double that of import tariff bands. If the Cess on per unit of imports are added, the number of Cess tax bands can easily exceed fifteen. A considerable portion of imports into the country (especially final consumer products) are taxed both at maximum import duty of 25% and maximum import Cess of 30-35%. In addition, these products are also subject to PAL at 5%. This brings total import taxes on these products to 60-65% of landed value.

These unreasonably high import taxes protecting producers serving a small market of 20 million consumers has several negative economic outcomes. First, lack of competition in the domestic market discourages domestic firms from becoming more productive and innovative. Second, lack of competition leads to domestic prices being artificially high forcing consumers to pay higher prices. Third, high taxes on imports restrict consumer choice by restricting the variety of products available at different prices. Fourth, they create an anti-export bias; ease of making profits in the local market due to low competition and higher prices discourage the domestic firms from exporting. Fifth, high cost of products (e.g. construction materials) negatively affect investments. Thus, quite rightly, there has been discussions on the importance of reducing taxes on trade, specially “Cess”.

Although economic merits of reducing trade taxes (or eliminating some taxes such as Cess) are clear, the country faces three challenges when moving forward in this direction. First is the negative short term impact this will have on the trade deficit. Second is the possible short term negative impact it can have on government revenue. Third is the painful adjustment costs imposed on the domestic industries that benefit from higher taxes on imports.

Reducing trade taxes will release pent up demand for imports

Most final consumer goods ranging from agricultural products, processed food, other final consumer items as well as construction material are subject to both high import duty and high import Cess. As a result of higher taxes leading to higher prices, the demand for these products at present is held down artificially. Reducing or removing taxes such as Cess therefore will lead to lowering of prices and release of pent up demand for imported products.

In addition to that, the foreign exchange rate, despite the fall seen in the past few months, still remains overvalued. This coupled with the low interest rate regime will provide a further boost to imports. In 2015, the impact of the expansion of expenditure on consumer goods imports (due to reduction of taxes) on trade deficit was offset to a large extent by the savings made from lower prices on oil imports. However, in future, further savings the country can make from lower oil prices will be marginal.

Increase in imports will not be a concern, if export revenues can increase at the same or a higher rate at the same time. However, growth in exports have remained sluggish since 2011. In the first eight months of 2015 exports have declined by 3.4%. The likelihood of seeing a significant boost to exports in the short term is low firstly due to weak demand for exports resulting from global economic slowdown and secondly due to structural and supply side constraints faced by the export sector that cannot be fixed in the short term.

Therefore, a significant reduction of taxes on foreign trade under these circumstances can lead to a significant expansion of trade deficit. In addition, release of pent up domestic demand for imports and resulting increased competition and downward pressure on prices will impose painful adjustment costs on domestic industries that benefitted from higher taxes over a long period of time.

Reduced trade taxes: Bust or boost to government revenue?

A critical macroeconomic challenge faced by the government at present is reversing the declining trend in its tax revenue. As a ratio of GDP during 2000-2014, tax revenues have dropped from 15% to 11%. The country has failed to address structural issues and administrative inefficiencies of its tax regime over the last several decades, such as widening the tax base, simplifying compliance, improving revenue collection, removing ad-hoc and complex tax exemptions. As a result, government continues to heavily depend on  taxes on international trade (over 90% of which is on imports) for its tax revenue. Therefore, the risk of reduced trade taxes leading to a decline in revenue is a concern for the government.

taxes on international trade (over 90% of which is on imports) for its tax revenue. Therefore, the risk of reduced trade taxes leading to a decline in revenue is a concern for the government.

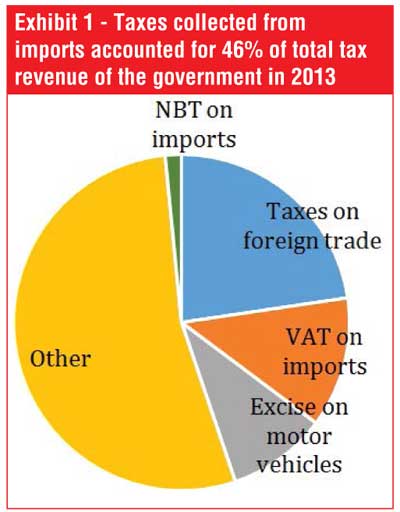

On average roughly around 50% of taxes are collected from taxing imports. As demonstrated by Exhibit 1, in 2013, 46% of total tax revenue of the country was collected from taxes on foreign trade. Out of this direct taxes purely on foreign trade (i.e. import duty, SCL, Cess, PAL) accounted for 18% of government revenue. The balance is collected from Excise, Value Added (VAT) and Nation Building Tax (NBT) on imports. The Cess on imports accounted for only 3% of the total tax revenue. The direct hit of removing import Cess therefore is a loss of roughly about 3% of tax revenue. For a country with already a low tax revenue level even this small reduction may sound alarming.

In reality however, increase in imports and resulting increase in tax revenue collected from other taxes collected from imports (e.g. import duty, VAT, NBT, PAL) can possibly offset the loss of revenue resulting from the reduction/removal of import Cess. Depending on the size of the increase in imports, it may even boost government revenue in the short run.

Gradual tax phase out will help cushion the negative impact

The impact of reduced trade taxes on trade deficit is a concern, given the likelihood of this triggering pent up demand for imports especially at a time when the prospects of boosting exports in the short term remain bleak. The overvalued exchange rate coupled with the low interest rate regime and low foreign exchange reserves makes the situation only more toxic.

The government however can reduce the impact on trade deficit by adopting several safeguards. First is allowing the exchange rate to be market determined. Attempting to maintain an overvalued exchange rate will further boost imports and lead to further depletion of already low foreign exchange reserves of the country. Second is to adopt a phased out approach in reducing taxes. This will prevent a sudden surge in imports. This will allow the government to better understand the response of demand to changes in import prices and better manage the impact on revenue. Further, it will provide space for domestic industries to gradually adjust to increased competition.

(The writer is a Senior Economic Analyst of Verité Research, a private think tank providing strategic analysis and advice to governments and the private sector in Asia.)