Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Thursday Feb 26, 2026

Monday, 8 August 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

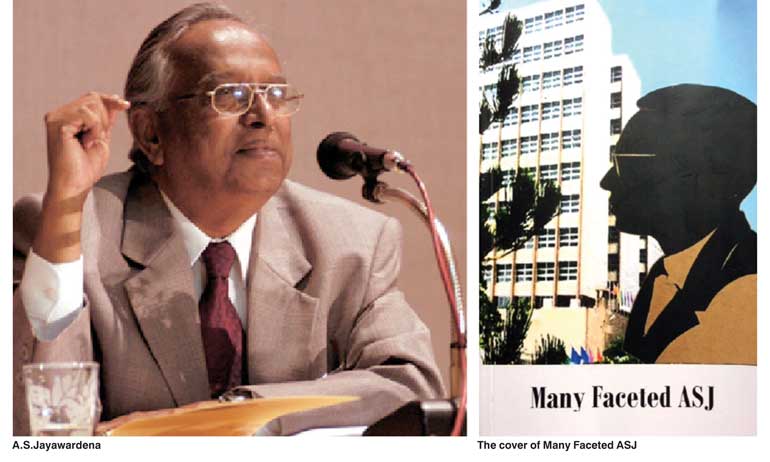

Many Faceted ASJ

Amarananda Somasiri Jayawardena, fondly addressed as AS by his friends, celebrated his 80th birthday last week. His friends, followers and disciples got an opportunity to pay tribute to this legendary man at a simple birthday party organised by his children. A booklet, titled ‘Many Faceted ASJ’, containing contributions by 19 of his friends and followers was also issued to mark the occasion.

Those contributions had looked at many aspects of his personal, family and professional life. Yet, a missing point in them was the philosophy this man was having, the challenges he faced and how he managed to overcome those challenges. Hence, this series intends to bring out the economist living inside him. It is based on my earlier writings on him and the long experience with him spanning over four decades.

The hard taskmaster with a human face

AS was a hard taskmaster with an obsession for perfection. Hence, he was not popular among his subordinates. He was noted for being hard on them whenever he observed faulty reporting. But, he was a different kind of a boss.

AS was a hard taskmaster with an obsession for perfection. Hence, he was not popular among his subordinates. He was noted for being hard on them whenever he observed faulty reporting. But, he was a different kind of a boss.

Unlike some bosses who used to throw a faulty report at your face in anger, he would sit down and improve it laboriously. In the process, he might make some uncomplimentary remarks at you. Yet, at the end, he would make you wiser and your report better. That was AS’s approach to his subordinates. He was guided by a simple philosophy on improving systems - one should not disturb a system if it worked well. However, if it was imperfect, he would painstakingly introduce improvements until it became perfect. Hence, nothing could pass through him without careful scrutiny for defects and a search for improvements.

The indefatigable man being stimulated by caffeine and tobacco

His whole career – he wore many different hats as a top economist, top civil servant, top banker, top international official and top central banker – has been characterised by his enormous drive to attain perfection in everything he could set his hands on. He would sit at his desk with a flask of coffee on one side and a packet of cigarettes and an ashtray on the other. Then he would work for hours and hours writing, editing or improving a report.

An ordinary person who is engaged in this type of work will soon exhaust himself but AS, invigorated and energised by the two stimulants on his table, would not stop his work until he was fully satisfied that he had done a perfect job.

The joint study on tea industry

I first read about AS in 1969 when I was an undergraduate at the Vidyodaya University. It was my habit to read Parliamentary Debates or Hansards and one day I came across a speech delivered by Ronnie de Mel, then an opposition legislator, extensively quoting a research paper published by two Central Bank economists, A.S Jayawardena and Nalini Jeyapalan, on Ceylon’s tea industry. The versatile legislator blamed the then Government for not heeding the wise counsel offered by the two economists.

Visiting lecturer at Vidyodaya University

Later in the same year, a senior student specialising in economics at Vidyodaya told me that one A.S. Jayawardena was taking their lectures in microeconomics. He had taught them that day a difficult topic called ‘Consumer’s Surplus’. By then, I had learned a simple treatment of Consumer’s Surplus and was puzzled why it was regarded as a difficult topic. I not only conveyed my feelings to him but also volunteered to explain it to him.

Offended by my naïve presumptuousness, he pulled out his notebook and asked me to explain to him how “compensating variation and equivalent variation” affected consumer’s surplus. The welfare aspects of consumer’s surplus underlying AS’s teaching became clear to me only when I did my graduate work decades later.

After that, I was constantly alive to many of the radical ideas he expressed in various publications.

Arguing against popular views

In a pamphlet on Public Sector Industrial Enterprises in Ceylon published by the Industrial Development Board in 1970, he argued that, treating a popular criticism at that time in a lighter vein, appointing defeated political candidates to offices in public enterprises did not necessarily mean an unsuitable choice. That was because such candidates had already displayed the spirit of competition and entrepreneurship having conducted, though unsuccessfully, difficult election campaigns. All that was necessary was to get them to maximise profits of public enterprises by using their inbuilt talents.

AS had spoken of the need for public enterprises to make profits at a time when it had been commonly accepted that their goal should be “service to the community” and “not profits”.

A new view on the first atomic bomb explosion

In another article he had written to the magazine of the Central Bank’s Sinhalese Cultural Association, Ulpatha, he had once again challenged the then accepted view that justified the US’s dropping of atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima in a bid to end World War II on the Eastern Front.

Quoting various sources, he had argued that by the time the atomic bombs were dropped, the war on the Eastern Front had ended and the only reason for dropping the bombs was to test the destructive powers of this newly-built military weapon. Hence, for him, those victims in Nagasaki and Hiroshima were just guinea pigs.

So, by the time I joined the Central Bank in 1973, to me, AS was a radical who looked at everything with an unconventional eye.

Meeting AS after he retired from active work

I have spent the whole of my career in the Central Bank spanning almost four decades with this giant of an economist. Therefore, his ideas, views, philosophy, world outlook and interests were all well known to me. But, to write this profile, I spent about four hours  with him at his residence in suburban Colombo surrounded by antique furniture, antique wall clocks, antique drums, antique brassware and many more antique items, all neatly placed in the sitting room catering to one’s aesthetical senses and representing the outcome of a hobby of a lifetime.

with him at his residence in suburban Colombo surrounded by antique furniture, antique wall clocks, antique drums, antique brassware and many more antique items, all neatly placed in the sitting room catering to one’s aesthetical senses and representing the outcome of a hobby of a lifetime.

His wife Lalitha, who has been his shadow through weal and woe, played her well-known role of pleasant and amicable hostess to us.

The ill of the tea industry

To begin the conversation, I asked him about the article on the tea industry co-authored with Nalini Jeyapalan. My question took him back to 1960s.

“Both Nalini and I met in London in the early 1960s when we were on study leave. We found that the entire tea trade in Ceylon, for that matter the tea trade in the whole world, was controlled by 10 or 12 firms in London which had extended their octopus tentacles towards every aspect of the tea industry, from cultivation to branding to shipping to trading. It was a giant cartel which could not be beaten by a small country like ours.

“But, at that time, there was a popular view that tea was ours and we should have the power to decide on its destiny. We wrote four articles which were published in the Central Bank Bulletin because at that time we didn’t have a separate publication at the Bank. The message we delivered was that the cartel was insurmountable and Ceylon should be very cautious if it tried to change the winds on its own. If we make any wrong move in haste, the cartel could destroy our whole tea industry because they had the control over everything,” he revealed.

Caution against unplanned action

His answer puzzled me. I asked him if he was an anti-colonialist. “No,” he said categorically. “Many thought that our articles had an anti-colonialist flavour. But that was not so. We simply analysed the existing situation in the world’s tea trade and cautioned against unplanned moves.” Fair enough, I contemplated. But, did this study receive the attention it merited?

“Yes and no,” he said. “No, because it was treated as yet another research study by my colleagues in the Bank. Yes, because, it had been read by Colvin R. de Silva who was the Minister of Plantation Industries in the United Front Government in 1970s. Colvin invited me to join his ministry as advisor cum head of planning and help him to restructure the newly nationalised plantation companies.”

Colvin, the leftist who supported profit-making

This puzzled me more. Wasn’t AS an advocate of capitalist economics and Colvin a diehard Marxist? How could they, holding polar views, become common bedfellows and work for a common goal? I expressed my surprise.

“Many tend to forget that Colvin was an educated down-to-earth politician. He was thoroughly knowledgeable of the destructive state enterprise system that prevailed in the Soviet Union. He didn’t want a repeat exercise of this destruction here in this country. So, he was against the then popular idea of breaking up the nationalised plantations and distributing them among the landless peasants, which was promoted by such slogans as ‘land to the tiller’. He retained many experienced and efficient planters to run these plantations. His advice to them was that they should run them profitably and pay out a bigger portion of profits to the Government. This philosophy and my own convictions matched with each other perfectly.”

AS’s role in protecting nationalised plantations

But the objective of the land reform program implemented at that time was to go for a socialist economy like one with collective farms, I recalled. That was one of the missions of the Land Reform Commission or LRC of which AS was also a commissioner representing Colvin’s interests there. Did he have to keep silent at those LRC meetings? I was curious to know.

“Colvin’s instructions were very clear. Do not break up good plantations and destroy them, because they were a part of our national wealth. But, I had to carry it out very carefully and cautiously, because except another commissioner, all others were all for it.”

AS used the tactic of continuously explaining and educating his fellow commissioners. The solid training he had got at the London School of Economics or LSE regarding the failure of such systems in the Soviet Union and in Indonesia helped him to articulate his arguments. Then, he began to reminisce once again.

An all-night Peduru Party

“There was an all-night educational session similar to a Peduru Party where we were all seated on mats in a circle and tried to educate ourselves of the virtues of setting up collective farms. There were LRC commissioners, its officials, young men and women who were potential members of the collective farms, etc.

“One official explained the virtues of collective farms, another how they are run and a third the rights and obligations of members including how the surplus is distributed. Everybody appeared to be highly excited because this was a novel idea being tested in Sri Lanka. They were all of the belief that they could develop a man pursuing only the common interests of society divorced from his personal interests. My LSE training told me that this would not work because the personal interest, sooner or later, would superimpose itself on the much praised common interest. But I couldn’t tell them so because in that excitement any counter-opinion would have been regarded a traitorous activity. So I was waiting impatiently for an opportunity to speak.”

“Did you get an opportunity?” I asked him.

Self-interest is more powerful than common interest

“Yes,” he said. “Then, there was a young man at the back and he rose to his feet. He pointed to a girl nearby and said that they were to be married soon. Then, he made the odd request at that time. He asked for a half an acre so that he could cultivate it with his wife and lead a good life. All those who were present and had been advocating the collective farming system were stunned beyond description. But, it gave me the opportunity to explain to them that collective farms had not worked either in the Soviet Union or in China or even in Cuba. I told them that personal interests always prevailed over common interests. So, we would be destroying these good estates – or national wealth as Colvin had named them – if we tried to convert them to collective farms. At the end, they all agreed that small unproductive parcels could be collectivised, while the efficient larger ones should be left intact.”

AS is an ardent free market advocate now but was he like that throughout? If it is not so, when did the change take place? I ask him.

A socialist converted to free market enterprise

“Like any young man of the day, I was inclined to socialism when I was at the University of Ceylon,” he admitted. “The real change took place at LSE. Many think that LSE is a seat of leftist orientation because of the leadership given by Sydney Webb, its founder and the fames of Harold Laski. This may perhaps be true for its political science faculty, but not for its economics stream. LSE earlier had such fierce free market advocates like Friedrich von Hayek who wrote in 1940s the famous book, The Road to Serfdom, criticising the socialist type of state managed economy system. I didn’t have an opportunity to study under him, but his legacy had been left behind and others had taken it forward.

“So, people like Lionel Robins, Jack Wiseman, Alan Peacock, Eric J Mishan, I.M.D Little and Richard Lipsey took the mission forward. They taught us and encouraged us to self-discover, as seekers of truth, that the incentive system under a state economy system didn’t work properly as in the case of a free market economy. It was an unlearning and relearning process for me. I read a lot, argued with others and was finally convinced that behavioural economics dictated that the inborn self interest in man can’t be changed by socialist type human-engineering. So, when I completed my MSc at LSE in 1965, I was a changed man.”

AS has also completed an MPA degree at Harvard University, USA, during 1974-75. How did that prestigious institution contribute to make him what and who he is today? I wondered.

Solidification of economic philosophy by Harvard

“Harvard solidified my convictions. We studied under a galaxy of great economists like Kenneth Arrow, James Dusenberry, Charles Kindleberger and Richard Musgrave. The subtle philosophical side of welfare economics and its relation to other fields like public economics and monetary economics was imparted to us by Harvard.

“Harvard like LSE encouraged us to make a self-discovery. We learnt how market failures invited government intervention. At the same time, there were government failures which were worse. Also, economic freedom, widespread information and good governance contributed to economic development.

The learning which you make by yourself is a solid foundation which is ingrained in your system forever and on which you can build up your knowledge base later. It is not like memorising and passing examinations,” he says with an enormous sense of modesty.

It makes me think of him in a different way. He is one of those who got the rare opportunity of studying at the two best institutions of higher learning on both sides of the Atlantic and then blending that knowledge into a distinct philosophy of his own.

In the next article we will look at his contribution to Bank of Ceylon, first as its General Manager and later as its Chairman, two positions he held on release from the Central Bank.

(W.A Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, could be reached at [email protected]).