Monday Mar 02, 2026

Monday Mar 02, 2026

Monday, 27 March 2017 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Students claim that education is not a commodity

‘Education is not a commodity’ has been a popular view almost universally held by Sri Lanka’s student community in higher learning institutions. For them, it is non-negotiable. Even some university academics at the country’s state universities have been ardent proponents of this view.

This view held by them is now a public commodity found everywhere. It could be found on the placards which students wave at people when they stage streets demonstrations. It is also demonstrated during television discussions on education issues in which both students and academics participate. Or simply, it is stencilled in bold letters on the walls of state universities. All this points to a synthesis – now formed into a common opinion – created by those who have a stake in the country’s education system. But what is missing in this synthesis is a lack of a careful analysis of whether education is a commodity and if so why it is and if it is not a commodity, why it is not.

A society cannot supply all the commodities through a system of community funding The objection to education as a commodity comes from the general dislike which many harbour in them about markets. A commodity is demanded by its users and supplied by producers at a price in the market. Those who are unwilling or unable to pay the price are denied the opportunity for using the commodity, however much it is essential for their existence or wellbeing.

For the continued existence of societies this should be the rule, since it calls for equal sacrifice by both users and producers making it a fair exchange.

A society cannot continue to allocate resources for the production of the commodities needed by its members unless they are paid for by somebody. If the user cannot pay for it, the whole society should get together and pay for it as a community. But this cannot be done for all the commodities in use, since it amounts to collecting money from each member of society, creating a pool and then, using the resources in the pool to pay for the production of the commodities that are demanded.

To administer such a system, society has to set up systems at a cost. Money spent on those systems is a waste. This is because the resources so spent too could have been used for producing other needed commodities. But when the user pays for it, there is no need for such systems and the entire payment and exchange process is decentralised to an individual level with no additional cost to society.

Such a system is thus both effective – because it delivers what it intends to deliver – and efficient – because it is done at the minimum cost to society. Hence, societies have to decide clearly which commodities should be produced on a community basis and which commodities should be produced on a personal basis. Accordingly, the selection of community production of commodities is done after a careful analysis of the essential nature of the commodity from the viewpoint of the general welfare of the members of a society.

Community funding is necessary for public goods

For long, such community production has been done in case of commodities of which the market system fails to collect payments from users and make them available to producers. This arises in a very special situation where a person cannot be denied the opportunity for using a commodity whether he pays for it or not. A common example often mentioned is the eradication of an epidemic.

For instance, with the dengue epidemic which has hit Sri Lanka today, the eradication of the dengue causing mosquitoes will benefit everyone living in a particular area irrespective of whether they have paid for it or not. Hence, no producer will step into taking measures for eradicating the epidemic.

As a result, society should get together and finance the production of this commodity on a community basis. These commodities are known in economics as ‘public goods’ and there is no question about the Government intervening in the production of such commodities for the benefit of all citizens.

Education provides additional social benefits

But education is not such a commodity where the market system would fail. That is because the user of education can be denied the opportunity for using it if he does not pay for it. Hence, the market system can produce the commodity called education and supply it to society.

But there are some reasons for society to get together and finance education expenditure on a community basis. That is because education provides additional social benefits to societies which are not counted by individuals when they choose to spend their own money on education.

Education improves human capital

First, when everyone in society is educated, skilled and competent, it improves the production capacity of society enabling it to continue to create wealth and prosperity. Such qualities are commonly known as ‘human capital’ and the existence of quality human capital is a prerequisite for creativity, inventiveness and innovativeness of societies – a must for progress in a highly competitive global environment.

Societies that lack them, as the Sri Lankan writer Munidasa Kumaratunga once remarked, will not rise in the world. Hence, the continued advancement in societies will be dependent on the level of education attained by all members of society.

Education is a way to narrow inequality

Second, education helps societies to narrow the income gap by facilitating the members to attain what is known as ‘social mobility’. Social mobility is the opportunity afforded to members of society to break away from family, caste, ethnic or racial constraints and move up on the social and income ladder according to his desire and ability.

Hence, it is the gateway for people to move to a higher level of social stratum thereby automatically narrowing the income gap or inequality in society. If inequality persists, it breeds social, political and economic disorder leading to an eventual break-up of even strong and advanced societies.

Education creates good citizenry stocks too

Third, while improving the human capital stock, education also improves a society’s good citizenry stock as well. When educated people are numerous  in society, it boosts art and literature. It also develops more responsible citizens who are capable of self-governing and participating in democratic processes in a more effective and responsible manner. It also helps societies to keep a check on the breeding of crime. In a nutshell, education elevates a society from a primitive level to an advanced level where there is better social interaction and social collaboration. Creating such an advanced civilisation is the wish of all modern societies.

in society, it boosts art and literature. It also develops more responsible citizens who are capable of self-governing and participating in democratic processes in a more effective and responsible manner. It also helps societies to keep a check on the breeding of crime. In a nutshell, education elevates a society from a primitive level to an advanced level where there is better social interaction and social collaboration. Creating such an advanced civilisation is the wish of all modern societies.

Education is a merit good warranting public production

However, these social benefits arising from education are not taken into account when individuals decide on the level and type of education. They take into account only their private benefits which are lower than the social benefits. Hence, the demand for education by private individuals falls short of what society desires as its optimal level. Thus, though education can be produced and supplied as a private commodity, it merits being produced as a commodity financed by the community on a collective basis.

Such commodities are known as ‘merit goods’ in economics. Thus, education still remains a private commodity that could be produced by the private sector, but societies have chosen to supply it as a community financed commodity on meritorious grounds.

This is the only reason for saying ‘why education should not be a commodity’ but it is not non-negotiable as claimed by university students in general and supported by a select group of academics.

Education model is freaky

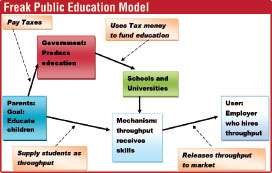

This is because education has a peculiar property when it is produced either as a commodity traded on the market or on a community basis by society. It is different from the normal commodities that are produced in an economy as shown in the chart.

In a normal commodity, the market system itself assures the quality of the commodity being traded in the market. In this case, the person who places the orders for the commodity in the market is the person who pays for it. Hence, he has an incentive to demand value for the money and if the producer supplies him with a substandard commodity, he has the right and incentive to reject it. If he continues to reject it on the grounds of substandard quality, the producer goes out of business. Knowing this risk, the producers too have an incentive to produce and supply quality products.

No incentive to ask for quality

But in the case of education, as the chart shows, the order is placed by parents for the education of their children. In the case of public education where funding is done by community, payment is made by the Government which in turn collects the needed money from members of society by way of compulsory taxation.

But the production is done by the school or university system, as the case may be, engaged by the Government for this purpose. Schools hire teachers and lecturers as inputs to produce education.

Students are a throughput anxious to get a certificate

Students are simply throughputs who go through the education machinery. They spend a given number of years inside the machinery, roughly 13 years in schools and a further three to five years at universities or technical colleges. They are expected to acquire wisdom, skills and competencies whilst going though the machinery. Since the students are simply a throughput, they have no incentive to insist on the quality of education they receive.

Similarly, though it is parents who place orders for education, they too have no incentive to ask for the required quality standards from the institutions that produce and supply education. Both parents and students just need a certificate to give signal to prospective employers who will hire those throughputs that have come out of the education machinery.

Thus, at this level, teachers and university academics have no compelling reasons for maintaining the required quality standards.

Employers too cannot ask for quality standards

The users of the output arising from education are the prospective employers who will hire the throughputs. But since they do not pay and they enter the scene only at the last lap, it is too late for them to ask for the quality standards in education. Since they will hire a substandard product, they will simply be victims who have to spend extra money for bringing the hired throughputs to the required quality levels.

Students and teachers have allowed the system to rot

Students and teachers have allowed the system to rot

Hence, in the public education system, students will do everything – demonstrating on the streets, ragging fresh students and attending funerals of relatives of colleagues and so on – except studying. And also, university academics too do not have incentive to insist that students should be in classes. Thus, a perennial epidemic in Sri Lanka’s university system has been the absence of students from classes.

This was eloquently presented by Professor Sunethra Weerakoon who retired recently from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura having served that university as a mathematics-don for 40 long years.

In a paper she presented at a seminar held at the university recently under the title ‘Institutional and Cultural Corruption within Public Universities: an Urgent Policy Challenge for the Government’, she has documented the pathetic situation at state universities in Sri Lanka as follows: “A primary indication of the flaws in the student culture is poor attendance at lectures. At my own university, the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities reported to the Senate in October 2016 that over 200 students had zero attendance at lectures. Furthermore, after perusing their grievances, 108 were permitted to sit the final examination. When asked whether it is proper to allow students to sit the examination without attending a single lecture, he said, ‘If we didn’t give permission for them to sit the examination, they wouldn’t allow other students to sit it’. Not only does this example illustrate the low levels of commitment of many students to their university education, it also illustrates the unacceptable laxity of university authorities to the problem,” (p 16).

Education as a merit good being supplied by the state has been betrayed

Thus, the production of education as a merit good in Sri Lanka has been betrayed through a destructive cultural practice adhered to by students and lecturers. The only way to bring back the required quality standards to educational institutions is by forcing them to face competition from privately produced educational institutions in where parents would place the order, pay for it and demand quality assurances from the respective institutions.

In other words, state sector educational institutions, while performing the major role in producing education, have to be supplemented by private sector educational institutions that would provide effective competition to them.

Education as a commodity is negotiable

Hence, education is certainly a commodity irrespective of whether it is produced by the state sector or the private sector. Hence, the students’ claim that it is non-negotiable has no foundation.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])