Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 30 June 2017 00:10 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The Constitutional Assembly in the Parliament of Sri Lanka hosted Dikgang Moseneke, the former Deputy Chief Justice of South Africa and an architect of the South African Constitution, to deliver a lecture on ‘Reaching a consensus on the Constitution: The South African Experience’.

In his introduction, our Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe, briefed the gathering about the progress at the Constitutional Assembly. Modalities of devolution are mostly agreed upon he said, but issues about the nature of the executive, centre-periphery relations and electoral reforms are yet to be ironed out. He further said that the present constitutional reform process is very different from the ones in 1972 or 1978 because this Assembly will not be debating a cut and dried document, but a document with options from which to choose for some of the key issues.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the nature of the electoral systems to be adopted by the three levels of government is a key determinant of the other two key issues – i.e. the nature of the presidency and centre-periphery relations. In fact, the executive presidency, the current proportional representation system of elections and the centre-periphery power relations currently exercised through a governor appointed by the President are interdependent components of the present constitution and those should not been dismantled heedlessly.

PR systems do not typically allow majority governments. The only time Sri Lanka had a governing party with a majority in Parliament was in 1988 and 2005, both being special circumstances. The Parliamentary election of 1988 was held during terrorism in the south led by the JVP. The Parliamentary election of 2015 was held during the euphoria that followed the defeat of terrorism led by the LTTE. In all other elections since the PR system was introduced in 1978, governments secured less than the 113 seats required for a majority in the Parliament.

The provision for awarding a bonus seat for the winning party in each of the 22 districts is in place to give an edge to a party which is close to getting a majority in Parliament, but in practice, the bonus seats have been distributed between the two major parties and a regional Tamil party, making the bonus an ineffective policy instrument.

The Executive Presidency has provided stability to governments in the past, but its excessive powers has led to abuse of that power. Powers of the President have been curtailed through the 19th Amendment to the Constitution but a total abolition is also on the table.

Idealists want us to borrow ideas wholesale from Germany or New Zealand and argue for the wholesale adoption of those methods without considering the cultural or historical differences between our countries. In that regard it is heartening to see that the government has reached out to South Africa for good practices.

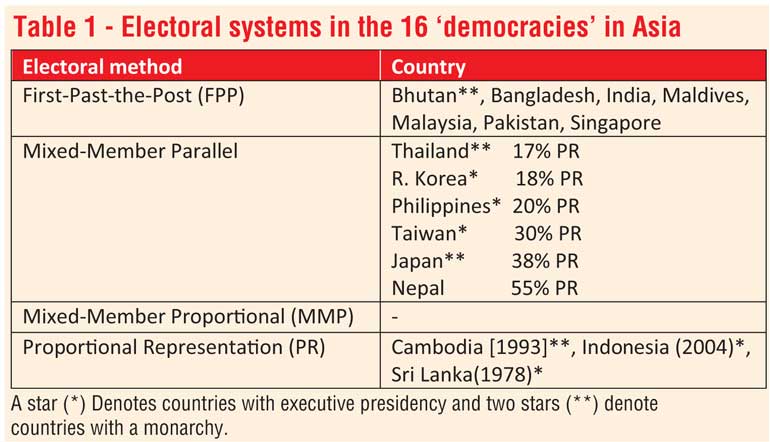

Another country to which we should pay attention is Indonesia, I believe. That country and Cambodia along with Sri Lanka are other three countries in Asia with a PR system of elections. Indonesia and Sri Lanka elect an executive president by popular vote and Cambodia has a monarchy (Table 1).

Bhutan and countries with British Commonwealth heritage (i.e. Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Malaysia, Pakistan and Singapore) continue to follow the FPP method while countries in East Asia have adopted “Mixed-Member Parallel” systems. However the PR component in such systems is nominal at ~20% in some cases. Nepal recently adopted a method where 55% of the seats are awarded on a PR basis and the other 45% returned by FPP contests at constituencies.

The author’s inquiry to IFES Chief of Party for Indonesia and Sri Lanka at the International Foundation for Electoral Systems elicited the following response regarding the electoral system in Indonesia:

“Thank you for your email to David Ennis and Beverly Hagerdon, IFES’ Chiefs of Party for Indonesia and Sri Lanka, regarding information on electoral system reform in Asia.

As you might know, Indonesia switched to an open list system (with districts of roughly the same size as Sri Lanka) with the expectation that it would foster greater control by voters. However, for various reasons, the open list system seems to have contributed to vote buying and a weakening of party discipline. The Indonesian parliament is currently debating alternatives to the open list system, but has not yet adopted changes. One of the key issues it is debating is the size of electoral districts. Indonesia has both national and regional parliaments and the national parliament has already been reduced from 3-12 to 3-10 seats per district, but regional parliaments still have 3-12 seats per district. A proposal is being considered to reduce the size from 3-10 to 3-8 seats per district for national parliament. The range is obtained through an empirical study based on the representation of the political diversity of Indonesia.”

As can be seen, Indonesia, a neighbouring country, too is struggling to replace the PR with open lists or PR with preferential voting as we call it in Sri Lanka.

According to the election guide of IFES, in the House of Representatives (DPR or Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat) in Indonesia, 560 members are elected by open list proportional representation in 77 multi-member constituencies to serve five-year terms. Parties must receive at least 3.5% of the vote to win seats in the DPR. Each voter receives one DPR ballot listing all political parties and candidates running in their electoral district. The voter then punches one or two holes to vote for one candidate or one political party or both. Parties must clear a threshold of 3.5% nationwide, increased in 2012 from 2.5%. Each party list must include at least 33% female candidates.

Interestingly, the electoral system used for regional councils is the same PR-open lists but the local councils seem to elect members on a FPP basis.

In South African elections the political parties reign supreme. Voters have one vote each at the elections to the National Assembly. Seats are allocated in 10 multi-member constituencies via party lists. One constituency is a national or ‘at large’ constituency and nine others represent each of the nine provinces.

If Sri Lanka used a similar system, voters in each province in Sri Lanka will be presented with a closed list of candidates from each political party contesting in the province and the all the voter has to do is to vote for a party. For example if three parties contest in a province and the seats are distributed proportionately as. say, 35, 30 and 3, among the three parties, the highest ranked such number of candidates from each party list are returned as MPs. Presently under discussion is such closed list system but for constituencies returning three to five MPs such that the MPs are closer to the voters.

Of the 400 members of the National Assembly in South Africa, half are selected from national lists and the remaining half are selected from regional lists. The regional elections too are held according to a ‘PR-closed list’ method, but local council elections are held according to an MMP system.

As we can see, electoral systems vary across countries and within countries they vary across different levels of government, In Germany national and provincial elections are conducted under MMP systems but local elections under the PR-closed-list method.

It is unfortunate that our Parliament has been discussing electoral systems since 2003 without seeking adequate outside expertise. Electoral reforms considerations in Sri Lanka are driven by formulas and ways of optimising formulas without a deep understanding of the concepts behind those numbers or good practices across the world.

Currently we have legal provisions for an MM-Parallel system enacted for local councils and the old PR system is still in play for Provincial Councils and Parliament. An MMP system for the Parliament is on the agenda, but the document put forward by the steering committee is just another set of numbers without an in-depth analysis situating such numbers in a larger electoral reforms framework.

To my knowledge only a Norwegian consultant secured by the Center for Policy Analysis was invited to make presentations to the committee. He advocated an MMP system having already decided it is the best method for Sri Lanka. I too have been discussing MMP method as an option since January 2015, but our Parliament and the public deserve the services of a technical committee bringing wider range of experiences and outlooks.

Following up on the visit by Moseneke of South Africa, the Constitutional Assembly should convene a team of technical experts with international experience to present to Parliament the options for electoral reforms not just for Parliament but for all three levels of government. Such reforms should take into consideration the issues that are already on the agenda for the devolution of power and the nature of the executive presidency. Such a team could include experts from Indonesia and South Africa, the consultant from Norway who has already done much work and personnel from the International Foundation for Electoral Systems, for example.

Better late than never.