Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Tuesday Feb 17, 2026

Friday, 30 September 2016 00:11 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

In an ironic twist, last Saturday marked an epoch in the lifespan of two nationalist movements in the island’s north and south.

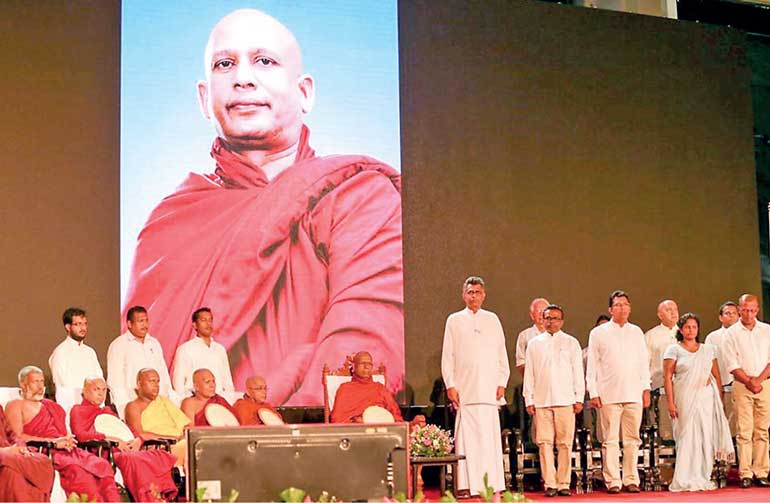

In the capital Colombo, the Jathika Hela Urumaya used its 13th National Convention at the Sugathadasa Indoor Stadium to shed its saffron image, with Omalpe Sobitha Thero stepping down as party leader. When it first won seats in the 2004 parliamentary elections, the JHU was a party dominated by monks who rode a wave of sympathy in the wake of Soma Thero’s death in 2003. Rabidly nationalist in the first 10 years of its existence, the JHU began a process of political evolution in 2014, when it backed the common candidacy of Maithripala Sirisena against Mahinda Rajapaksa, whose presidency had afforded them ministerial positions and driven their ideology into the political mainstream.

Over the past year as it ruled in coalition with the UNP, a party it has consistently been at cross purposes with, the JHU has been in quiet transformation. The Sinhala nationalist party has softened its positions on the ethnic question and even accountability. In August, the party sent a senior representative to an event to commemorate victims of enforced disappearances, who hailed the recent passage of the Office of Missing Persons Act. Nishantha Sri Warnasinghe said that while the JHU believed that the past was best forgotten, the party understood that families of the missing from all ethnic communities would feel differently.

At its convention last Saturday (24), the JHU appointed Deputy Minister Karunaratne Paranavithana co-chairman of its party, to further bolster its progressive credentials.

With the exit of Theros Omalpe Sobitha and Athuraliye Rathana, the JHU is now within the decisive control of the party’s strongman and Presidential confidant Champika Ranawaka. For some time now, the suave and articulate JHU politician has been fashioning himself as a ‘pragmatic nationalist’, setting himself apart from the pro-Rajapaksa bandwagon and Sinhala chauvinist groups like the Bodu Bala Sena and Ravana Balaya. It has long been suspected that Minister Ranawaka harbours lofty political ambitions, and that this recent shift towards centrist politics is part of a larger strategy to make give him broader political appeal.

Less clear is whether the JHU General Secretary has truly shed his ultra-nationalist ideology as he embarks upon this political transformation, or whether those inclinations will remain dormant until he wields effective control over the state apparatus one day.

Champika and the constitution

The timing of his reinvention is interesting, with political parties in hectic negotiations to hammer out a deal on the new constitution. A key facet of those negotiations is devolution, or power sharing proposals aimed at resolving an ethnic conflict that has spanned 60 years.

Minister Ranawaka is part of the 21-member steering committee that will ultimately present the new constitutional proposals to the Constitutional Assembly that was established by resolution of Parliament earlier this year. If he opposes the new arrangements being proposed, Ranawaka will no doubt use the lobbying power he enjoys with the most senior sections of the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe administration to dilute a power sharing deal or overly enthusiastic proposals to abolish the presidency, which the JHU has historically never favoured. In this endeavour he will prove more effective than the Rajapaksa lobby which is fairly certain to oppose the new proposals tooth and nail.

Ranawaka will seek to influence the process as a powerful insider, by using his access to President Maithripala Sirisena. To make President Sirisena waver on the more problematic parts of the new constitutional proposals, would put the support of the SLFP for the new draft in question almost immediately. Without SLFP support, the draft constitutional proposals will not cross the two-thirds majority hurdle at the Constitutional Assembly in the first instance and will result in the dissolution of the Assembly and mark the end of the road in this attempt to finally set things right, 68 years after independence.

Ranawaka will seek to influence the process as a powerful insider, by using his access to President Maithripala Sirisena. To make President Sirisena waver on the more problematic parts of the new constitutional proposals, would put the support of the SLFP for the new draft in question almost immediately. Without SLFP support, the draft constitutional proposals will not cross the two-thirds majority hurdle at the Constitutional Assembly in the first instance and will result in the dissolution of the Assembly and mark the end of the road in this attempt to finally set things right, 68 years after independence.

On the other hand, if the JHU in its fresh avatar backs the draft constitutional proposals, power sharing arrangements and all, its evolution would be complete and Ranawaka’s launching pad for the next phase of his political career, as the less severe nationalist alternative to the Rajapaksa coterie, will be ready.

Northern dimension

In the North the ongoing deliberations on a new constitution have also provoked a response. Last Saturday, the Tamil People’s Council (TPC) under the chairmanship of Northern Province Chief Minister C.V. Wigneswaran held the Eluga Tamil (Rise Tamil) rally, which was aimed at raising awareness about ongoing militarisation, state-sponsored Sinhala ‘colonisation’ of the North, the need for an international investigation into wartime atrocities committed against the Tamil people, the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act and a political solution based on a federal model.

The rally was backed heavily by the Tamil National People’s Front led by Gajen Ponnambalam, TNA constituent parties EPRLF led by Suresh Premachandran and PLOTE led by Dharmalingam Siddharthan, and also received tacit support in the run up to the event from Douglas Devananda’s EPDP.

Mobilising for weeks, these parties managed to bring large crowds on to the streets of Jaffna, where organisers asked shops and businesses to shut down to allow people to participate in the demonstration. Thousands of Tamils marched through the streets of Jaffna to a park in Muttraveli for a public meeting. In what appeared to be a deliberate twist, the meeting reflected the mood and décor of the Pongu Tamil (Awaken Tamil) celebrations organised by the LTTE between 2001 and 2004.

Rallying point

For most of the organisers the Eluga Tamil rally last weekend was meant to be a rallying point for Tamils of the North, irrespective of political affiliation. The idea was to muster a large enough crowd to ensure Colombo and Tamil representatives negotiating on their behalf on issues including transitional justice and the constitution with the Government in the capital, sat up and took notice. The mass mobilisation worked and even by conservative estimates the rally drew a crowd of more than 8,000 people, a significant number in the electoral district of some 500,000 registered voters.

To draw crowds in Jaffna, the TPC and its allies had to ensure they did not take a hard line against the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK), the largest party in the TNA. In the August 2015 parliamentary election, ITAK polled nearly 70% of the vote in the five districts of the North. According to Tamil political analysts, any indication that the rally was part of an attempt to split the TNA would have jeopardised the organisers’ chances of drawing public support for the rally. Rather the TPC and fellow organisers were tapping into the sections of the community that supported a pan-Tamil unity position to lobby Colombo on the issues concerning Northern Tamils. For this reason, many of the speakers who took the stage, including Chief Minister Wigneswaran, who remains a member of ITAK even though he opposes many of the party’s positions, steered clear of attacking the TNA leadership for not backing the rally and took pains to explain that the demonstration was not an attack on ITAK or the TNA leadership.

Political observers explained this softer approach with the argument that keeping the TNA together was an important value in Tamil politics. None of the parties on the Eluga Tamil dais wanted to be responsible for promoting a split in the alliance.

Standing under an umbrella as he delivered his speech at the rally last Saturday, the Chief Minister said their differences with the TNA were “minimal”, explaining that their disagreements were mostly about timing.

A question of timing

For some time now, Wigneswaran has argued that the constitutional process to deliver a political settlement could not come before accountability had been effectively addressed. The assertion laid bare a sharp division within the TNA, with party leader R. Sampanthan promising the Tamil people on the campaign trail in August 2015 that they hoped for a negotiated settlement on Tamil rights and political autonomy before the end of 2016.

The Chief Minister has changed tack somewhat, now arguing that it was impossible to hold meaningful negotiations on the constitution until the North was completely demilitarised and the Prevention of Terrorism Act repealed. Much of the subtext of the Eluga Tamil speeches laid emphasis on the constitution-making process. Speakers at the rally called the process secretive and warned that the Tamils would not know what proposals were being negotiated until the last moment.

The message emerging from the rally and its specific timing speaks to a section of the Tamil polity led by and backing the Chief Minister getting increasingly jittery as lawmakers in Colombo get closer to reaching consensus on draft constitutional proposals that will offer a political solution to longstanding Tamil grievances. The provocative nature of the slogans used to promote the demonstration – specifically the decision to lead with claims of Sinhala colonisation and the erection of Buddha statues – created the impression that Eluga Tamil’s true aim was to disrupt a delicate process of reconciliation and constitution-making by rousing nationalist sentiment in the South.

While most of the process of negotiation on the draft constitution has taken place in the shadows, it is now widely expected that the Steering Committee led by the Prime Minister will present its Interim Report to the Constitutional Assembly by November this year. While draft constitutional proposals could be appended to the Interim Report by this Committee as set out in the resolution passed by Parliament in March this year, it is more likely that the report will set out the broad framework of the new constitution, including the contours of the devolution proposals.

Once the broad contours of the power sharing arrangements are laid out, the TNA will go back to the people in the North and East to explain that as Sampanthan promised in 2015, the process was now in motion.

Political relevance

Naturally, this would put the Chief Minister-led TPC in a bind as it struggles to discredit the TNA for its ‘disconnect’ with the issues of people on the ground in Tamil dominated regions. In the year since the TNA swept the parliamentary polls in the north, the charge by the party’s political opponents, and increasingly its own Chief Minister, is that the Tamil party’s Colombo-based lawmakers had lost touch with the growing resentment and frustration of the Northern people.

This argument would be turned on its head should the TNA campaign in favour of the new constitutional proposals and return a ‘yes’ vote with a fairly large majority in the North and the East. And the underlying reality in the aftermath of the Eluga Tamil rally is that the TPC-led alliance will begin to disintegrate at the very inception of an electoral or referendum process. The TPC remains an unelected body with no popular mandate. The TNPF led by Ponnambalam failed to win a single seat in the 2015 parliamentary election, polling slightly lower than even the wildly unpopular UPFA in the North. EPRLF is led by Premachandran, who was also defeated in the August 2015 election. That leaves PLOTE and Siddharthan, who will almost certainly back the TNA in any electoral contest, not only because his electoral fortunes lie with the Tamil alliance but also because he is a believer in the process Sampanthan has put in motion, as the only chance at a political settlement for the next 20-30 years.

Under the circumstances, it is extremely unlikely that even the TPC will oppose the new constitutional proposals outright at a referendum. To lead a ‘no campaign’ on the constitutional referendum would be to pit itself directly against the TNA and the electoral powerhouse in the North that is ITAK. The Chief Minister for all his heroics as the true saviour of the Tamil people will be vulnerable without a party machinery to back his position in such a contest.

Nevertheless, the Eluga Tamil demonstration caused consternation in moderate Tamil circles, where it was seen as a culmination of extreme Tamil nationalism that has been sweeping across the North over the past few years. Gajen Ponnambalam’s hardline TNPF, which has been attempting to capture the political space in the North since the end of the war, the Tamil Civil Society Forum, which claims to be apolitical but pushes an extreme nationalist agenda and constituent members of the TNA like the EPRLF that want the party to adopt tougher positions, have found a home with the Tamil People’s Council. The protection of Chief Minister Wigneswaran, who won a thumping mandate from the Tamil people in 2013, offers these politicians, who have failed badly at recent elections, a space to create a political forum for themselves, says Political Economist and researcher Ahilan Kadirgamar.

Together, none of the parties backing the Chief Minister were able to win a single seat in Parliament, Kadirgamar says, indicating that they do not have much support from the people. “Their electoral base is very thin – comprising mostly of the professional classes within Jaffna and the Jaffna-based media. As a result, they are projected in a much bigger way than they really are. This is largely as a result of their control of the local media which is generally supportive of them,” Kadirgamar said.

Together these forces constitute a type of middle class base for the TPC that the Tamil Diaspora relates to, he explained.

Support for the rally was also largely concentrated in the peninsula other observers said, with very little interest in Eluga Tamil in the Wanni and the Eastern Province.

Leverage in negotiations?

Chief Minister Wigneswaran and his fellow travellers may believe that mass demonstrations to raise awareness and hype about the mostly legitimate concerns of Northern Tamils will give Tamil political representatives leverage in their negotiations on devolution and accountability with Colombo. But reactions to the demonstration in the South have been predictably severe.

Almost one week after the rally, Wigneswaran’s statements continue to dominate the headlines, with nearly every political party in the South strongly opposing his positions and condemning the Chief Minister for trying to create ethnic tension. Far from strengthening the TNA’s bargaining position then, Eluga Tamil has pushed even progressive sections of the Government that are sincere about delivering a political solution into a corner, forcing them to take positions against demilitarisation and federalism; greatly diminishing the chances of hammering out a meaningful power sharing arrangement that will address minority grievances especially in the North and East.

Meanwhile, the Chief Minister’s antics have unleashed a wave of nationalist hysteria in the North that will need to find an outlet.

Something very similar happened in Vaddukodai in May 1976. When moderate Tamil leaders led by S.V.J. Chelvanayakam and Appapillai Amirthalingam adopted the Vaddukoddai Resolution at the first Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) national convention, calling for the constitution of the separate sovereign state of ‘Tamil Eelam’, a Tamil youth insurgency was already on the rise. The resolution was also intended to be a clarion call to young Tamils. Youthful passions, already stirred by liberation struggles for statehood in other parts of the world in that era, found impetus in the Vaddukoddai resolution which called on the Tamil youth in particular to “come forward to throw themselves fully in the sacred fight for freedom and to flinch not till the goal of a sovereign state of Tamil Eelam is reached”. The resolution led to the launch of the Tamil militant struggle; a struggle that now had the blessings of the elder statesmen of the Tamil polity.

At the time, TULF leaders may have believed the militant youth insurgency in the North could be effectively used as leverage for negotiations on greater self-rule for the Tamil dominated provinces with Colombo. What transpired of course was a markedly different story. The militancy intensified. Prabhakaran’s LTTE would violently wipe out or subsume all other militant groups to become the main Tamil guerrilla group fighting Government forces. As the organisation grew increasingly brutal, Tamil political moderates became their first targets for assassination. One by one, the LTTE wiped out the Tamil political leadership, nearly all of them erudite cultured statesmen whose brilliantly articulated arguments for Tamil political rights were silenced by a far more brutal negotiator, one who perceived the moderates to be conceding too much.

After Vaddukoddai, the ‘boys’ Tamil political leaders had nurtured and inspired by their fiery rhetoric and impassioned appeals would silence the community’s moderates for three decades. Only once the LTTE was finished could the renaissance begin for moderate Tamil leadership. Sampanthan, who has watched the Tamil struggle come full circle, has decided to trust that moderate positions will win the day. He knows, perhaps better than anyone else alive today, what devastation the inflaming of passions in the North by movements like Eluga Tamil can bring.

Strange parallels

For independent researchers like Ahilan Kadirgamar, these parallels seem clear. Until last Saturday, the extreme nationalism taking shape in the North had been limited to rhetoric and resolutions in the Northern Provincial Council. Kadirgamar says the move to bring people on to the streets the way the Eluga Tamil demonstration did, allows the right wing political movement to take on a different dynamic.

In the Northern Province, where unemployment rates are high and alcoholism rampant, young people are constantly seeking an alternative political movement to engage with. Kadirgamar says the inability to offer an alternative socio-political vision to engage the youth is an abysmal failure on the part of the TNA and ITAK or the Federal Party.

“When you take 8,000 people on to the streets, it gives a message to the youth. This is worrying because this group has no strategy or game plan going forward but it is mobilising street protests. By failing to give proper direction to the youth you are unleashing something you can’t control,” Kadirgamar told Daily FT.

In addition to fuelling extreme Tamil nationalism, Kadirgamar says movements like Eluga Tamil led by the TPC also create anti-Muslim and anti-Sinhala feeling among the population and takes away from the possibility of rebuilding relations between the communities.

And quite clearly when such sentiments and movements take root in the North it strengthens Sinhala chauvinists in the island’s south.

Today, the Bodu Bala Sena will rally in Vavuniya, where a significant Sinhalese population is resident, to oppose positions taken by Wigneswaran last Saturday, particularly those that target the Sinhalese minority living in the Northern Province. Bodu Bala Sena rallies, recent history has demonstrated, have a tendency to go badly awry. Some political observers predicted the development soon after the Eluga Tamil rally last weekend.

“Sinhalese nationalists and Tamil nationalists are friends. They are objective allies. They need each other,” says Kadirgamar.

Researchers like Kadirgamar blame the TNA/ITAK and the Sirisena-Wickremesinghe led Colombo establishment for failing to use the political space that has opened up since the fall of the Rajapaksa regime. Rather than create a discourse and debate about reconciliation and a political solution in the North, the issues are limited to a group of experts negotiating in Colombo, the Political Economist told Daily FT.

The entire focus in Colombo is the prevention of a Rajapaksa resurgence, says Kadirgamar. Even Government members admit that fears that extreme Sinhalese nationalists led by Rajapaksa will scuttle the process to bring about peace between the communities and a political solution to end decades of ethnic strife, has driven the constitution-making and reconciliation processes into the shadows.

Kadirgamar says this is an ineffective strategy.

“It’s leaving the space wide open for extremists to capture and tap into resentment and frustration,” he said.

Over the next few months, Sri Lanka will step into a crucial phase of its constitution building process. For the better part of six months that process has flown under the radar but barring any complications details of the negotiations will be made clear within the next two to four months.

The TNA is confident it will win support for the proposals it has played a major role in negotiating in a referendum. If the national coalition of the SLFP and the UNP hold, it should be able to carry the south.

Nationalist mobilisation in the north and the south is a reaction to these developments. A settlement on the national question will threaten the political survival of both groups, so nationalist movements on both sides of the ethnic divide will launch a fight to the death to scuttle the enactment of a new constitution.

The most sustainable solution moderates in the north and the south can offer to counter this devastating brand of politics taking shape in post-war Sri Lanka is a constitution that upholds the rights of minorities and marginalised groups, effectively decentralises political power and delivers equality and social justice for all.