Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Monday, 24 October 2016 00:01 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Above 7% growth is needed to sustain the economy

Sustained growth is normally viewed from two different angles today. One is from the point of environment and depletion of non- renewable resources. The other is from the point of a country’s ability to sustain a high economic growth based on technological advancement, infrastructure and quality of human capital. Economic growth involves the delivery of an ever increasing high volume of material goods and services to people.

renewable resources. The other is from the point of a country’s ability to sustain a high economic growth based on technological advancement, infrastructure and quality of human capital. Economic growth involves the delivery of an ever increasing high volume of material goods and services to people.

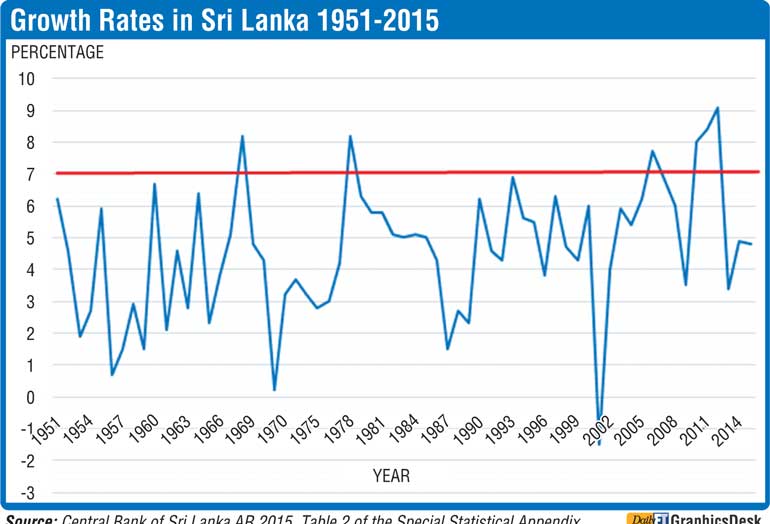

It requires an economy to transform natural resources into final goods and services by using a combination of technology, physical capital and human resources. If the rate of annual expansion of the volume of goods and services, known as real GDP, is above 7% for a significantly long period, that economy is hailed as a high growth achiever on a sustainable basis. There is a reason for using the benchmark growth rate of 7% as the minimum. This is because GDP will double roughly in every 10-year period, if growth occurs at 7% annually at a compound rate. Thus, at this growth rate, within 30 years or in a single generation, Sri Lanka will be elevated to the rich country club. The sustainability path so marked at a growth of 7% is interrupted, if the growth rate becomes volatile and falls below the minimum level for many years. A country desirous of attaining sustained growth has to take appropriate policies to avoid this possibility.

Environmental issues should be tackled at global level

Environmental issues and their consequential global as well as local manifestations eroding the welfare levels of people are in the forefront of economic policy discussion and global action today. Since it is akin to the financing and production of a global public good, it needs to be addressed by consensual global action reinforced by supportive local policies.

The global community is far away from reaching agreement on such a consensual action program. Hence, in the meantime, the most pressing problem faced by emerging economies like Sri Lanka is the elevation of the respective economies to a high growth path that would eventually uplift the welfare level of the peoples of those countries. Therefore, this address will look at how fiscal reforms are imperative for the attainment of the second aspect of sustainable growth, namely, the continuous expansion of the material goods and services produced within an economy.

A volatile growth below 5% on average

Sri Lanka’s growth numbers show, as presented in the graph, a high level of volatility since independence. From 1951-2015, the country’s growth rate has been on average at 4.7%. In this long 65-year period, spikes representing growth rates of above 7% have been recorded only in six years. Even then, they are a way apart from each other except for a brief period during 2010-2012. All others have mostly been troughs below 5%. Thus, Sri Lanka’s material growth has not been a sustainable one posing the serious challenge of lifting the economy to a continuous high growth path.

This poor achievement has been made by the country despite the avowed goal of all the governments to make it a rich country within a single generation. That goal has been elusive moving away from Sri Lanka every time it tries to reach it. The problem has become more complicated as some empirical studies have shown such as the joint study done by IMF researchers and a local economist that the country’s actual growth initiatives have been above its potential growth (available at: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=41414.0).

The implication is that the growth has been attempted through expansionary fiscal and monetary policies raising the aggregate demand above the aggregate supply causing an overheating in the economy.

The outcome has been manifested by above average inflation within the domestic economy increasing the cost of production and thereby eroding the country’s competitiveness, on one hand, and putting pressure for the exchange rate to depreciate against other major currencies, on the other. Thus, how to generate a sustained growth has been the most pressing development challenge which the country is facing today.

A bad track record in fiscal policy

Sri Lanka’s past fiscal policy has a very poor track record. Ministers of Finance come up with budgets with ambitious fiscal targets, hail their products as ‘development budgets’ and spend more time in criticising their predecessors instead of proposing strategies for the future.

Sri Lanka’s past fiscal policy has a very poor track record. Ministers of Finance come up with budgets with ambitious fiscal targets, hail their products as ‘development budgets’ and spend more time in criticising their predecessors instead of proposing strategies for the future.

Private sector chambers too join Finance Ministers in calling those budgets development oriented and business friendly just by looking at the handouts delivered to them. However, there is no mid-term or year-end review of budgetary achievements, though it is now a requirement under the Fiscal Management (Responsibility) Act enacted in 2003.

Though these reports are published as required, they seldom conform to the requirement of presenting analyses of achievements against targets and why such targets have not been achieved, if they have failed to attain them. There is no ex post review of the budgetary achievements against the targets so that the Ministers of Finance could rectify the mistakes they have made.

Budgeting is a process which requires continuous review, identification of deviations and making amendments to current strategies to address those deviations. If this process is not followed, the fiscal situation of the country begins to deteriorate year after year, reaching a situation where the country is unable to improve the conditions without making sacrifices on a massive scale or getting external support. Today, Sri Lanka’s fiscal situation is exactly in this condition.

Problems in the fiscal sector

Sri Lanka’s weak government sector is rubbing its inefficiency on all the sectors in the economy. It is conventional to name the private sector as the ‘engine of growth’. If so, the engine should have a driver and that ‘driver’ is none other than the government sector. If the driver is inefficient and incompetent, the engine cannot move. The responsibility for making the engine driver efficient and competent devolves on the fiscal policy. It requires the government to adopt a host of policies.

First, it has to prune the government sector which has grown beyond the country’s carrying capacity. Second, it has to decide on its priorities carefully allocating funds for future growth generating sectors.

Third, it has to reform the loss making public enterprises so that they would not be a burden to taxpayers. Fourth, the Government has to improve its revenue base so that it would be able to finance its ever-growing expenditure through revenues generated from taxes, profits and other sources.

Fifth, it has to put a stop to unnecessary expenditure programs that have become a drain of the scarce resources of the Government. Sixth, the budget has to be consolidated to reduce the ever-increasing public debt driving the country to an inescapable debt trap.

Seventh, waste, corruption, and profligacy in expenditure have to be eliminated promoting thrift at every level. Eighth, the current fiscal crisis should be recognised, communicated effectively to the electorate, and the painful measures waiting for the people should be properly marketed.

Past advice not heeded to

These issues have been discussed, analysed and debated at various public forums in the past. To its credit, the themes of most of the previous annual sessions of the Sri Lanka Economic Association had covered these issues. The Presidential Addresses made by the SLEA President, Professor A.D.V. de S Indraratne from 2004 to 2014 at those annual sessions and now released as a book under the title ‘Policy Issues for Sustained Development in Sri Lanka’ have critically analysed those issues.

In addition, the Institute of Policy Studies too has analysed these issues in its annual publication, The State of the Economy, which is normally released prior to the Budget Speech by the Minister of Finance. Hence, I will focus in this keynote a few salient issues that need be addressed urgently.

Heading toward a debt crisis

One issue is Sri Lanka’s high public debt levels that have eaten up almost the entirety of the Government revenue for servicing the same. The recorded public debt as a percent of GDP has declined from above 100% in early 2000s to a level of around 72% over the last five-year period.

Apparently, this shows an improvement but behind this improvement, there are a lot more to be reckoned with. Sri Lanka’s commercial external debt is rising, posing problems for future debt sustainability. A recently made charge in this connection has been that the total indebtedness of the public sector has not been recorded in the government debt office which records only the borrowings of the central government. Thus, it is charged that it has left out a large segment of borrowings by public sector institutions.

Most of this extra-Treasury debt has been raised on the strength of guarantees issued by the Government and therefore if the public sector entities fail to repay, a contingency liability will fall on the Treasury to honour the same. The problem has been further complicated by the use of the commercial external debt raised at high costs for unproductive infrastructure projects without proper cost-benefit analyses or viable business plans. Hence, the burden of maintaining such unproductive infrastructure projects as well as servicing such debt has fallen to the country’s taxpayers.

Loss-making SOEs

Another salient issue has been how the loss-making public enterprises could be turned around to enable them to contribute to the public coffers. The leading loss-makers in the past decade have been SriLankan Airlines, Mihin Air, CEB, CPC, CWE and CTB.

The annual losses of these five public enterprises have been more than Rs. 100 billion. The implication of such loss-making for the budget has been that its scarce resources have to be used to keep them going. Since the annual running cost of a mid-size university is about Rs. 2.5 billion, these loss-makers have forced the nation to sacrifice about 40 mid-size universities.

The Ministry of Finance had emphasised in the past that public enterprises should deliver an adequate return to the Treasury on the investments it has made. However, no concrete action was initiated by the Ministry to force these enterprises to deliver positive returns. There is an initiative made by the present Government to restructure the loss-making public enterprises. Yet, the progress has been slow and in the interim, the Treasury has been forced to fund their losses so that they could keep their balance sheets clean and continue to borrow from commercial banks.

One mistake made by the present Government is the decision to amalgamate two sick persons, SriLankan Airlines and Mihin Air as from the beginning of November, 2016. Since both are sick, the Treasury will have to pump money to keep both sick persons going. It will increase the taxpayers’ liability rather than easing the same.

Friction between monetary and fiscal policies

A third, perhaps very important, issue has been the non-coordination between the fiscal policy adopted by the Ministry of Finance and the monetary policy adopted by the Central Bank. Thus, when the Central Bank tightens monetary policy to fight inflation, the Ministry of Finance introduces measures which weaken the Central Bank’s action.

A good example was the tightening of the monetary policy by the Central Bank in July 2016 by increasing its policy rates by half a percent. The objective of this measure had been to curtail the expansion of the aggregate demand above the aggregate supply and thereby causing inflation and bringing pressure for the exchange rate to depreciate. Almost immediately, the Ministry of Finance announced the granting of the duty free car importation facility to public servants stimulating the demand and negating the action taken by the Central Bank.

Unwarranted bailouts

A fourth area of concern is the bailing out of the fraud-stricken bankrupt financial institutions by using public funds or Central Bank’s money printing ability.

One example is the money made available by the Treasury amounting to Rs. 4 billion to pay out to the alleged depositors of the bankrupt credit card operator, the Golden Key Company.

Neither the Government nor the Central Bank has an obligation to do so since it is a company that operated illegally as a deposit-taker. Then, last week, the Central Bank has outdone the Government by making available a sum of Rs. 16.5 billion to bail out a bankrupt primary dealer and three finance companies (available at: http://www.cbsl.gov.lk/pics_n_docs/latest_news/press_20161018e.pdf).

Solving Entrust issue without legal provisions

The primary dealer, Entrust Securities, has reportedly defrauded investors who have paid that company to buy government securities on their behalf. The amount involved has been estimated at Rs. 12 billion. The Bank has proposed to lend Rs. 8 billion to a Special Purpose Vehicle managed by Seylan Bank to enable the manager to accumulate interest for eight years by investing the same in a government security and pay the investors out of the interest income so earned.

SPV is required to return the original Rs. 8 billion to the Bank at the end of the eight-year period. This lending is against the Monetary Law Act or MLA which has authorised the Monetary Board to lend only to commercial banks and NSB for meeting liquidity shortfalls against the collateral of prescribed securities, only for a period at the maximum of nine months. This restriction has been introduced to prevent the Board from lending to others causing inflation, on the one hand, and leading to frauds, on the other.

Hence, the Board is exposed to possible criminal liability charges in the future. In this scenario, it is advisable that the Monetary Board re-examine this proposal before its implementation.

Opening Pandora’s Box

The three finance companies involved have been Standard Credit Finance, City Finance Corporation and the Central Investment and Finance. The Bank is expected to make out these payments out of its deposit insurance fund or DIF which has sufficient resources at present. But given the liability which will fall on it on account of other sick financial institutions, it is questionable whether this measure adopted by the Board is prudent.

Further, the Bank has opened Pandora’s Box by using its money printing machinery and funds in DIF to bail them out since it creates a bad precedent for future would-be-defaulting financial institutions. It appears that its implication on the Budget has not been properly assessed by the Ministry of Finance. These bailouts reduce the Central Bank’s transferrable profits to the Government which the Budget 2016 had estimated at Rs. 13 billion in each of the years from 2016-2019. Since the Central Bank had made losses in 2015, it could not deliver the amount earmarked for 2016. A similar fate might befall the Treasury in 2017 and beyond in view of these imprudent bailouts. Hence, in the final analysis, both these liabilities will fall on the Budget.

Fiscal reforms a must

Thus, it is necessary that the government sector should be reformed in order to facilitate it to allow the private sector to function as the engine of growth. An essential element in the reform of the government sector is the reform of the fiscal sector to enable the Government to allocate more resources for production rather than for consumption. In this case, a prudent use of scarce resources under the Government’s fiscal reforms is a must.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])