Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Saturday Feb 07, 2026

Monday, 2 January 2017 01:15 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

A development bill running into a messy situation

The Unity Government managed to have its Budget 2017 passed in Parliament by a two third majority. From the public pronouncements which the top leaders had made, one could infer that it had boosted their sense of security in power to an unbelievably high level. Yet, it cannot expect the same Parliamentary success for its proposed Development (Special Provisions) Bill now before the public (available at: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2016/11/141-2016_E.pdf).

Eight out of the nine Provincial Councils have already rejected the Bill. It will be a matter of time for the ninth one – the Eastern Province Provincial Council – to follow its counterparts. Some of the coalition partners of the Unity Government, including some senior Ministers, have expressed their concern about the Bill in public; the Opposition has vowed to defeat it in Parliament when it is taken up for debate later this month. Independent media too have taken a critical stand on the Bill. So have the civic rights activists. Their objection is mainly to one particular provision in the Bill: The creation of a super minister or two super ministers with absolute powers over the entire government machinery thereby relegating the President and the rest of the Ministers to an unimportant position in managing the economy. They fear that the ‘juggernaut of the two super ministers would annihilate the sense of good governance, participatory engagement in development and economic freedoms of the people.

Economic democracy requires the Government to consult people

This type of critical reviews of the Bill, done whether in good faith or with ill-motives, is a salutary development. It shows that the public is no longer a passive spectator of what is being done by those in power. It is in accord with the promise made by the present Government at the last general election that it would deliver “economic democracy” to people if elected to power.

Economic democracy means that choices are made by people and not by those in power and the rulers would engage the public in a fruitful public consultation when they propose those choices for them, as clarified by this writer in a previous article in this series (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/472845/Part-II--Delivering-Economic-Democracy-will-lead-to-controversy-unless-it-is-defined-properly ).

Yet, the Government has failed to establish a fruitful consultation process for the Bill it has proposed. The criticisms against the Bill have sprung up as a natural reaction to change and not in response to any move taken by the Government to invite public views. So far, the Government has not made any clarification on the Bill, leaving the entire electorate completely in the dark. Its unexplainable silence has enabled those who criticise the Bill with ill motives to win the public over to their side. Hence, it is another instance of communication failure by the Unity Government which has come to power promising all avenues for productive public engagement in vital policy issues.

Apparent inaction to fix the ailing economy

This Government inherited a sick economy and its duty was to fix the economy as quickly as possible (available at: http://www.ft.lk/article/587456/Economy-2017--The-alarming-signs-should-not-be-ignored ). Given the country’s perilous budgetary, external and public debt records, any program to fix the economy would have been painful to everyone, demanding ‘thrift’ on the part of all those from the very top to the bottom of society. Hence, the Government should have placed before people a rapid action program for review and approval. But, what was done in public was limited to an announcement of an economic policy statement by Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe in Parliament in November 2015 followed by a Budget for 2016 that had not taken its vision into account. Hence, the statement in the eyes of the public remained just a wish list on paper.

Then, after one year, the Prime Minister made another economic policy statement which did not have any connection to the one already made one year ago. Neither Parliament nor civil society debated the two policy statements. Hence, for all practical purposes, it seemed that the Government has been inactive in fixing the economy. As such, when the new Bill was gazetted, it shocked the electorate arousing public criticism of and concern about the proposed mechanism.

An unpublicised management mechanism

But unknown to the public, the Government had introduced an economic management mechanism immediately after it got power in August 2015. This mechanism was not made public in terms of the economic democracy principles which it had promised to establish after being elected to power. But a detailed outline of the mechanism has been presented in the first Performance Report which the Prime Minister had submitted to Parliament in early 2016 (available at: https://www.parliament.lk/uploads/documents/paperspresented/performance-report-prime-minister-office-2015.pdf ).

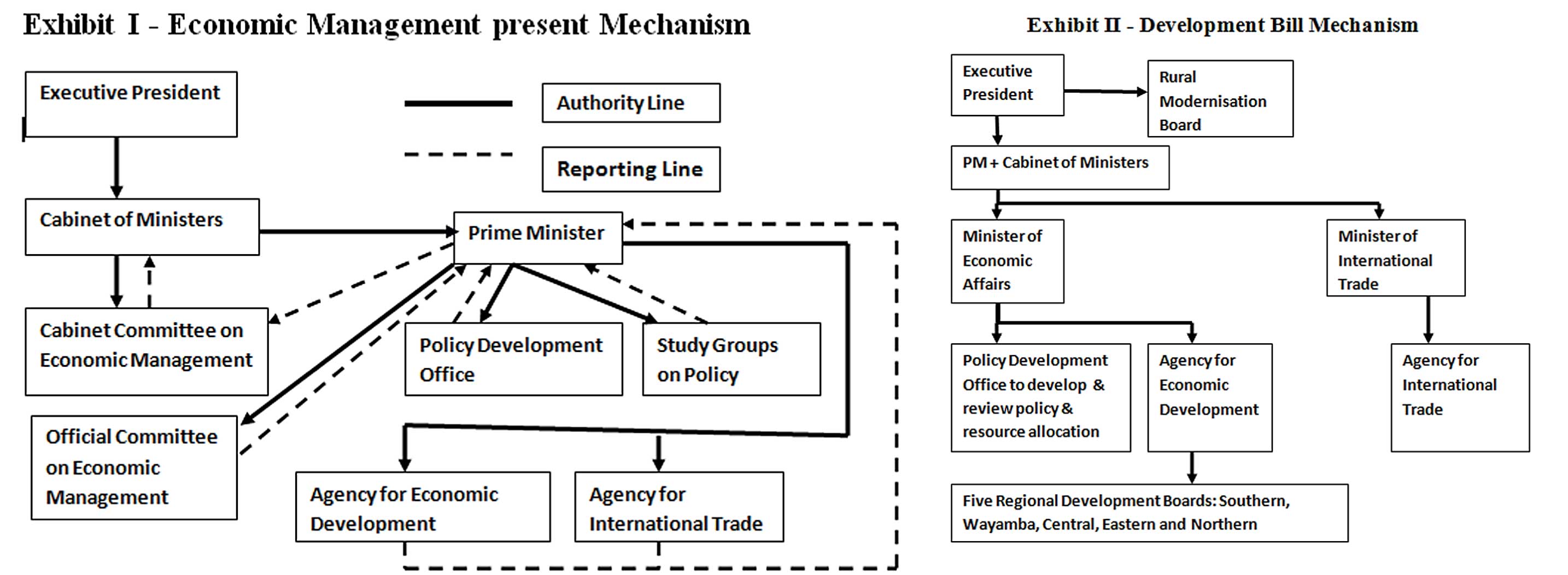

Once again, it was just another report filed away in Parliament without being reviewed, discussed or debated. Exhibit I presents an illustration of the mechanism that had been so introduced.

Cabinet Subcommittee on economic management

In terms of the mechanism in place, a Cabinet Subcommittee titled the Cabinet Committee on Economic Management or CCEM had been set up under the chairmanship of the PM by the Cabinet to make suitable recommendations regarding economic policies to be implemented by the government.

It had been made up of 11 senior Cabinet members representing all the parties in the Unity Government that have a stake in the country’s economic policy. The only exception had been the membership of the Minister of Law and Order whose role in economic policy making had not been very clear. The four functions assigned to CCEM, as given below, had in fact created not only one super minister but a team of 11 super ministers:

1. Examine Cabinet Memoranda relating to economic affairs, monetary and fiscal policy and financial affairs and submit recommendations to the Cabinet

2. Provide guidance in the preparation of the National Investment Programme, Public Investment Programme and facilitation of Private Sector Investment

3. Submit recommendations to the Cabinet on proposals involving economic and financial implications

4. Oversee the implementation of various legislations having a direct bearing on country’s investment/economic development

Thus, anyone who is opposed to the creation of a super minister under the Bill would have shown opposition to the Super Cabinet Subcommittee too.

Machinery under the Prime Minister

Under CCEM, there is an officials’ committee called Official Committee on Economic Management or OCEM again made up of five officials drawn from those who are close to PM and functioned in his office. Its duty was to assist CCEM in assessing the matters that had been referred to it for review and recommendation.

A Policy Development Office or PDO had also been set up in the Prime Minister’s Office, among others, to “to develop coherent, acceptable and equitable policies towards achieving Sri Lanka’s expansion goals”.

Its job had been very wide with functions similar to those of a traditional National Planning Secretariat. It had to formulate national policies, prepare a national policy framework, set development objectives and targets, coordinate the implementation of policies, review and evaluate the same and adjust the policy framework in light of the developments in the global economy.

Special agencies

Under the Prime Minister, a number of sector study groups had also been appointed to study and report on crucial economic issues. In addition, two agencies have been informally set up in the Prime Minister’s Office to oversee the implementation of the policies.

One is the Agency for Economic Development or AED and the other is the Agency for International Trade or AIT. Both function today under the powers vested with the Prime Minister by the Cabinet. Since they are two bureaus in the Government, their expenditure has to be sanctioned by Parliament in terms of the Constitution. So far, there is no evidence that Parliament has done so and therefore both these agencies it seems operate on funds allocated for other purposes.

Even today, PM is a super minister

Thus, for administrative purposes, the responsibility for managing the economy had been vested in the Prime Minister. But he had to apprise CCEM and through CCEM, the Cabinet of Ministers headed by the President of government’s economic policy framework. But this mechanism lacks provision for public consultation of key policy measures to be proposed and implemented by the Government. Despite that deficiency, it had been in place since September 2015.

Public officers should be smarter than the market

What is the economic rationale of setting up such a mechanism under the Prime Minister? First of all, it recognises that the Government is the key driver of the economy and the private sector should fall in line with what the Government proposes to implement.

In the absence of a consultation process, then, it falls on a handful of public officers, selected and led by the Prime Minister, to decide on the economic destiny of the country. Unless these officials have the market wisdom, what is being proposed by these officials through the Prime Minister would go counter to the market. It requires on their part to be blessed with triple sights – hindsight, sight and foresight – as pronounced by Frederic Bastiat when he distinguished a good economist from a bad economist as far back as 1850.

Hindsight helps a person to evaluate the successes and failures of past policies and serve as a guide not to do the same mistake again. Sight opens his eyes to what is happening today and manage the present events more tactfully and with wisdom.

Foresight enables him to identify the consequences of any policy which are not seen today but to be foreseen with wisdom. Experience shows that the public officers who work for salaries and therefore do not have to take risk on what they do but can pass it on to someone else are deficient of foresight, the most important sight out the three sights. One has to look at only how ETCA issue or rice importation issue has been bungled by the bureaucracy in the recent past for evidence.

An attempt to formalise the existing mechanism

In this background, what has been proposed in the Development (Special Provisions) Bill has been to formalise this informal economic management mechanism. Exhibit II illustrates how it operates in terms of the provisions in the Bill.

In this mechanism, there are a few departures from the existing arrangement. One such departure has been that CCEM has been substituted by two Ministers, one in charge of economic affairs and the other in charge of international trade. This has been the main issue of contention raised by those who are opposed to the Bill. Though the Bill is silent on it, there is nothing that would prevent the Cabinet led by the President to appoint a separate Subcommittee in the style of the present CCEM to review, direct and supervise what the two agencies and PDO are doing under PM’s supervision. Then, the proposed mechanism becomes identical with the present system as far as the reporting line and the authority are concerned.

Departures from the existing mechanism

Two other departures which are simply additions to the existing mechanism are the proposal to establish a Rural Modernisation Board under the leadership of the President and set up five Regional Development Boards covering Wayamba, Central, Eastern, Southern and Northern regions. There is no regional board for the Western Province since it is covered under the Megapolis project.

The existing 21 districts have been reassigned to form these five regions. Regional development will be the responsibility of the five regional boards under the direction of the two ministers concerned. Though the set up of the five regional boards has been a devolution of economic powers to the regions, eight provincial councils have rejected the Bill because in their opinion it is not a devolution in spirit since the powers are still vested in the Central Government’s Minister of Economic Affairs. This is contrary to Sri Lanka’s present plan to devolve more power to regions. Hence, it is a reasonable fear and in the name of good economic policy governance, it has to be eliminated.

Government should go for 3.0 communication strategy

As it is, the Development (Special Provisions) Bill has led to instability in the Government. That should not be the case. But the culprit is the Government itself which has failed to communicate effectively what it is planning to do and establish a mechanism to learn of the public’s views on its policy. Its communication policy is primitive, known as 1.0 communication in which it just tells what it wants to tell the people in a one way communication strategy. But modern communication policies are 3.0 policies, an advanced medium over the 2.0 policies that had replaced 1.0 policy a way back.

In a 2.0 policy, the public can respond by saying yes or no but cannot interact with the communicator. Popular web-based polls are 2.0 policies. But in the 3.0 policy, the public has the same right as the communicator and can effectively interact with him by criticising his action or presenting alternative suggestions. Social media like the Facebook are a good example for a 3.0 communication medium. Had the government had such a mechanism in place, it could have avoided the present debacle plus many other such missteps it had taken in the past. Not only that, it would help the Government to safe-sail its future economic policy measures as well.

(W.A. Wijewardena, a former Deputy Governor of the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, can be reached at [email protected])