Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Saturday Feb 14, 2026

Monday, 4 January 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

India’s thriving automobile industry offers Sri Lanka a viable GVC opportunity - Reuters

The roiling debates around trade agreements and the newest topic of a bridge connecting India and Sri Lanka reinforce a view I have long held, that we are afflicted by multiple forms of the island syndrome.

The first form is literal. Unlike citizens of countries with land borders, we have a sharp mental image of shape of our country. Even if we have no first-hand knowledge, in our minds we know where the country ends (or begins). This makes it difficult for us to grasp the interconnected and globalised nature of our existence.

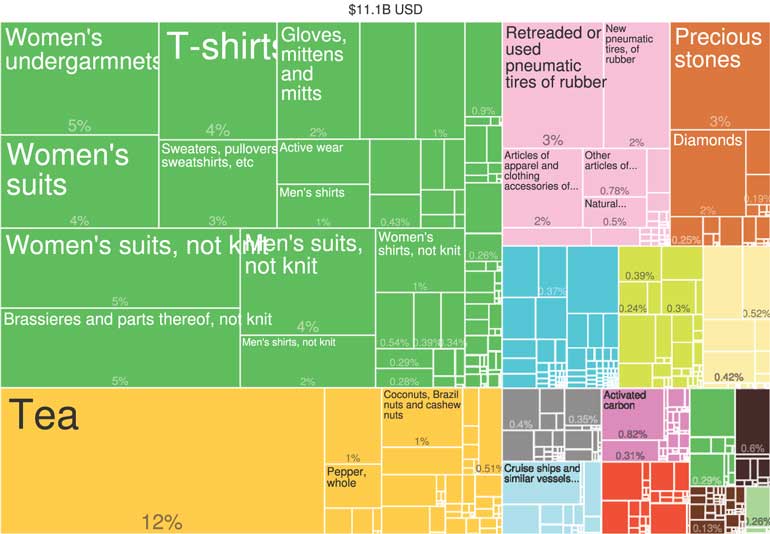

Over two million Sri Lankans work abroad. Our trade dependency ratio (total of imports and exports of goods and services as a percentage of GDP) was 53% in 2014. It has declined significantly over the past decade from around 75%, but it is still indicative of a reliance on the world for our economic wellbeing. Almost all our energy comes from abroad. The wealth of most of our people is correlated with the extent of their engagement with the outside world. In reality we are globalised; in our minds we practice juche (self-reliance, North Korea’s official ideology).

The second, and perhaps more insidious, problem is the insularity of islands. People here still think about trade using the kinds of analogies used in David Ricardo’s time (1772-1823). Actually that may be insulting to people of that time because they had a vibrant debate about Mercantilism which was more or less consigned to the dustbin of history with the repeal of the Corn Laws in Britain in 1846. We do not.

It appears they may still be teaching pre-Ricardian economics in the universities. It is the fate of some islands to become stagnant backwaters in the fast-running stream of intellectual discourse, especially when retrograde educational policies are in place as they are here.

Of course, trade policy is not simply about the contest of ideas. Industrialists, professionals and agricultural producers who benefit from protectionist measures and Indophobes play a role too; and, of course, the opinionated few who know little yet make no effort to find the relevant knowledge. I highlight the problem with the intellectuals because it is from them that one would expect some push back against the protectionists and some advocacy in favour of the future beneficiaries of sensible trade policy.

Global value chains

Global value chains (GVCs) have become a dominant feature of world trade, encompassing developing as well as developed economies. The whole process of producing goods (and services), from raw materials to finished products, is increasingly being carried out wherever the necessary skills and materials are available at competitive cost and quality. For example, the GVC for an iPhone runs through the US, Korea, Taiwan, the EU and China.

Removing frictions that hinder trade in services is essential for the efficient functioning of GVCs, not only because services link activities across countries but also because they help companies to increase the value of their products.

Investment is also a critical element. Depending on the circumstances, the firms engaged in GVCs would want to contract with independent firms, enter into joint ventures or establish affiliate entities.

GVCs are unavoidable if Sri Lanka is to escape the middle-income trap. Talk about promoting exports is obsolete. What we need to do is to reduce the frictions that make Sri Lankan firms unattractive for inclusion in GVCs. This includes policy uncertainty affecting investment and trade in goods and services. It also includes high transportation costs, time to move goods, and barriers to movement of key personnel.

Many of these issues can be addressed by actions flowing from legally binding commitments made in trade and investment agreements, usually described as comprehensive economic partnership agreements. The Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) are examples involving more than two countries. The now scuttled India-Sri Lanka Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement, if signed as originally planned, would have been a pioneering bilateral instrument.

Bridge too far?

What agreements and actions flowing from them cannot address are problems associated with transport. The volume and composition of trade between two countries may be explained using different models that include multiple factors. But common sense (and all the models) says that lower transport costs and time that are associated with proximity are a strong influence especially for trade in high-volume goods.

Many like to think that services trade occurring over telecommunication lines such as business process management/outsourcing is immune to the frictions of distance, but they neglect the importance of travel by key personnel from both buyer and seller.

It is true that services are a critical element of Sri Lanka’s economic strategy. But we cannot imagine that a services-only strategy can set Sri Lanka on a sustainable growth path to spring it from the middle-income trap. Our manufacturing firms must become integrated with GVCs. Investors must be attracted to locate GVC links in Sri Lanka.

What is a GVC with potential? The auto industry that has developed across the Palk Strait. The area around Chennai has attracted more than one third of India’s total automobile industry. Some project that it may become one of the world’s largest automobile manufacturing hubs by 2016 with an annual capacity of over 3 million vehicles.

Can the present transportation options permit Sri Lankan firms to join these GVCs, or result in Indian firms locating branch plants here that will function as links in GVCs? The very fact that this has not happened so far suggests that there may be merit in looking at ways to reduce transportation costs and time by ways including, but not limited to, a bridge connecting Talaimannar and Rameswaram.

Of course, no one builds infrastructure for a single use. I simply used the auto industry to illustrate. When the road or the railway or the port or the bridge is built, firms and entrepreneurs will come up with all sorts of uses. I am actually more interested in a cable that will interconnect the power grids, which would logically be part of the bridge. Plan B is an undersea cable.

Looking does not mean building. The numbers may not make sense. In any case, this kind of thing will take years to complete. But judging from the initial reactions of people accomplished in their own spheres, I feel this may be stillborn. Stuck in old thinking and unaware of the significance of GVCs, our opinion leaders are likely to let emotion override reason.

If in 1945, after the end of another bloody war, opinion leaders in France and Germany thought like ours, they would not have created the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to the European Union. The results of these perennial adversaries choosing to integrate their economies should give us food for thought.

In the absence of a modern economic discourse, matters are likely to be decided by atavistic fears of being overrun by Chola invaders. Not only modern transportation options, but GVCs themselves may be bridges too far for us insular island people.