Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Thursday Feb 19, 2026

Wednesday, 27 January 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Abolishing the executive presidency and reforming the electoral system are two key issues under consideration in the proposed constitutional reforms. During the 8 January to 19 June interregnum of 2015, a new President functioned under an old Parliament, but there was a sense of urgency for reforms as a result of President’s promise to both abolish the Presidency and reform the electoral process within 100-days of power. The two issues were to be addressed through Constitutional Amendments 19 and 20, respectively. Some Parliamentarians emphasised the importance of linking the two amendments, but their rationale may have been more political than functional. Amendment 19 was carried but short of abolishing the presidency. Amendment 20 was gazetted but not carried. Both will be reconsidered in the overarching constitutional reforms envisaged.

From a functional point of view, once an election is concluded, a Government has to be formed and the new Government has to make decisions. Even the most democratic process and the most representative result will not benefit a country if the newly-elected Government is not able to govern. It is well and good indeed that the current debates are focused on violence free and democratic election processes and a proportionality representative result that gives sufficient representation to minorities and smaller communities.

However, as I point out in this article, perfect or near perfect proportional representation in the Parliament in the absence of an executive presidency can lead to non-governable situations that we can ill afford. Unfortunately, there has been little analysis on the connection between proportionality of representation and governability. This article is an attempt to fill the gap and is based on a presentation by the author at a symposium jointly organised by the University of Peradeniya and LIRNEasia with the support from Campaign for a Free and Fair elections (CAFFE).

Need to balance proportional representation with governability

Proportional representation (PR) is the Holy Grail in electoral reforms. Understandably, the minority parties in Sri Lanka are focused on achieving result, which reflects the distribution of their communities across the island. It is in fact in the interest of all parties concerned to ensure adequate representation of minorities – ethnic or ideological, given our traumatic ethnic-conflict past and a history of violent uprising by the People’s Liberation Front or the JVP.

However, as political scientist Aurel Croissant (2002) argues, electoral reforms in a democratic system should aim at optimising the representational, integrational, and decisional capacities of the electoral system. By integration he means a party-formation process whereby a political system matures to yield a few strong political parties as opposed to a disintegration based on ethnic or religious or other narrow concerns. Since party-formation is also linked to governability, Croissant is essentially talking about balancing representation with governability. Horowitz, a professor of law and political science at Duke University takes a similar but more nuanced approach to identify six items for consideration in electoral reform. A close look reveals that those six issues too can be can be coalesced into the two major categories of representation and governability.

How has the PR system we had since 1978 affected governability and how would the proposed mixed member method system change the situation?

Mixed member method

The Constitution of 1978 transformed Sri Lanka from a ‘Parliamentary democracy with a ceremonial President’ to a ‘Parliamentary democracy with an Executive President’. The electoral system was changed at the same time from a majoritarian or first-past-the-post system (FPP) typical of a Westminster style government to a proportional representation (PR) system with a mechanism for awarding bonus seats to winning parties at each of the 22 electoral districts.

Currently, Sri Lanka is on the threshold of yet another constitutional change to abolish the executive presidency and move to a mixed member method of election. Mixed method of elections essentially combines two types of members of Parliament – those elected from constituencies on a first-past-the post (FPP) basis and additional members elected to bring the proportionality of the Parliament to the desired level.

The idea of a mixed method of electing members of Parliament (MPs) is not new. The Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC) on electoral reforms deliberated on the matter of mixed methods from 2003 to 2007. The 2012 Act to amend the local government elections was based on a 2007 interim report of the PSC.

In the 100+ days period between the election of President Sirisena on 8 January, 2015 and the dissolution of Parliament on 27 June was an active period in regard to electoral reforms. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party published a draft Amendment 20 to the constitution outlining a mixed method with 165 members elected on the basis of FPP and 90 on the basis of PR. A different model with similar numbers was discussed widely, but, the Amendment 20 gazetted by the ruling UNP was limited to 237-member Parliament. Both Drafts were critiqued, but the question of governability did not come up in these critiques. The obtuseness of the documents would have been a factor.

The Centre for Policy Alternatives (CPA), a Sri Lankan think-tank that has contributed much to the analysis of electoral reforms in Sri Lanka, strongly advocates an electoral system that yields 100% proportionality as in Germany or New Zealand (CPA, 2003 and 2015). Unfortunately CPA does not appear to pay sufficient attention to the socio-political context in Sri Lanka other than the ethnic problem.

Governability

v. representation outside of Asia

German Parliament of the Bundestag has a minimum of 600 seats with facilities for expanding the seats to accomplish near-100% proportionality in the final result. In regard to governability, in the 66 years under the current Constitution, there has been only one occasion (1957) when the largest party was able to govern on its own. Coalition governments is the norm in Germany. The composition of the present Bundestag, the 18th one in its history, has made even the efficient Germans to face difficulties and finally settle for a grand coalition or a coalition of two main political parties to avoid a crisis. According to a newspaper article on the 2013 general election in Germany:

“Germany’s main centre-left party (or SPD) cleared the way on Saturday for Angela Merkel (of the CDU-CSU coalition) to start her third term as chancellor, announcing that its members had voted by a large majority to join the conservative leader in government. It set the stage for Parliament to re-elect Merkel on Tuesday – ending nearly three months of post-election political limbo in Europe’s biggest economy.”

In New Zealand, the other exemplar used in electoral reform discourse, held its first mixed member election in 1996. Since then, neither the National Party nor the Labour Party have yet been able to govern on their own and have been compelled to form coalitions. The closest either party has come to governing alone was the 2014 election, when National won 60 seats, just one short of a majority.

In terms of the social-political culture, Sri Lanka cannot be more different from staid Germany or New Zealand. Those two countries may handle unstable situations, but, we Sri Lankans have to be careful about emulating their systems.

A comparison with Italy or with Spain would be more reasonable. In2005, tired of unstable governments, Italians voted to give a top-up bonus to the winning party to give it a majority. After that particular form of majority bonus was struck down by their Supreme Court unconstitutional, Italy adopted a system which guarantees a 54% majority to the winning party if it secures 40% or more of the vote in January 2015. A run-off election between the two parties would be carried if neither party has more than 40% of the votes. Once a winning party is selected, the 46% of the seats would be allocated to other parties in proportion to the votes they received in the first election.

Spain is another country where a majority bonus would be in order. In the recently concluded general election, power has been distributed among four parties with no two ideologically able to come together to form a government.

Governability

v. representation in Asia

Croissant (2002) identifies fifteen countries in Asia as being democracies. Excluded are Brunei, China, Laos, Myanmar, North Korea and Vietnam because they do not have multi-party elections held at the national level, according to him?

Of these democracies, the majority – i.e. Bhutan, Bangladesh, India, Maldives, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore – continue to use FPP-based systems leading to majoritarian results (Table 1, Line 1). Korea, Thailand, Taiwan, Japan and Nepal use the mixed member methods indented as Mixed Member Majoritarian (MMM) methods with the percent of PR allocation varying from a low of17-18% in South Korea and Thailand to 50% in Nepal. No country in Asia is yet to use the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) method that gives a result closer to proportionality. Simple PR methods are used in Cambodia, Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Indonesia and Sri Lanka both have Executive Presidents while Cambodia has a Second House, which is nominated by the Parliament and appointed by the King. Korea and Taiwan too have elected Presidents, but they are less powerful than the Executive Presidents of Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

See Table 1: All in all, Asian countries seem to tread carefully when it comes to implementing fully proportional or mixed member methods election.

Sri Lanka

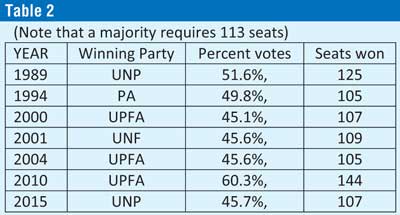

In the 26 years during which elections have been conducted under a PR plus preferential vote system, Sri Lanka has seen majority governments emerge only on two occasions, both being rather unusual. In 1989, the country was in throes of violence, in the North as well as in the South.

In 2010, the General Election was held immediately after a Presidential Election which was called shortly after the defeat and decapitation of the LTTE. In both cases, there were few constraints on the use of state machinery by the incumbent party. After 1989, the major contenders have been alliances. When alliances formed before the election proved inadequate, additional parties were brought in to ensure a majority.

It has been easier to cobble together governing coalitions after 2000, because of a Supreme Court judgment that negated the power of political parties to expel MPs who crossed over. This method was not used in latest Parliament of 2015. A peculiar form of grand coalition ensured a majority.

See Table 2

In the event the executive presidency is abolished, Sri Lanka should carefully study electoral systems used in Asia and other countries with similar ethno-socio-political contexts before committing wholesale to MMP systems used in developed and more disciplined societies like Germany or New Zealand.