Monday Feb 16, 2026

Monday Feb 16, 2026

Thursday, 4 August 2016 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

The three decades that followed the tragedy of July 1983 were perhaps the most painful years of our recent history

“Those who can make you believe in absurdities, can make you commit atrocities” – Voltaire

Much has been written about the fateful year of 1983. Most of the writings have been on the contributory factors that went to make that black event, the ferocity of the racial attacks during the rioting and the weak handling of the tragic developments by the authorities. The short and long term effects of that decisive occurrence has not absorbed the writers as much.

Such convulsions are not accidental events happening randomly. Invariably, there are long histories and social processes that precede them. As it broadly took the form of a racial riot, issues such as the complex relationship between the majority race and the main minority group, rising nationalism in a newly-independent country, a sense of exclusion on the part of the minorities in the making of the Republican Constitutions, an increasingly venal political culture, deteriorating standards in nearly every field, politicisation of the machinery of the State and the repeated failure on the part of succeeding governments to lead the country out of near systemic economic stagnation, undoubtedly played their role.

Before the traumatic convulsions of July of that year, there was an air of hope about the country. The post-1977 liberalisation had given the long-dormant economy a visible energy, the markets were active, once empty shop shelves were filled with goods, things were moving – a bus used to be a rare and irregular service, now the roads were busy with private buses competing for passengers, new ventures were coming up rapidly.

After nearly a decade of near death under Statist policies, which not only brought much of the economy under State control, but also looked askance at private enterprise, entrepreneurship was fashionable again. Small and medium businesses were opening up everywhere while the larger firms were busy supplying the ongoing Mahaweli project, originally planned for 25 years, now telescoped and accelerated. Some, carried away by the awakening economy, rushed to draw parallels with Singapore, the brightly shining economic powerhouse to the East.

Then came the July of 1983.

The three decades that followed the tragedy of that July were perhaps the most painful years of our recent history. In the number of casualties and the magnitude of destruction, Sri Lanka’s war(s) may not compare with the ferocious conflicts happening in countries like Syria and Iraq presently, yet the challenge posed by the LTTE, the seemingly invincible terrorist group, nearly undid this small country of limited resources.

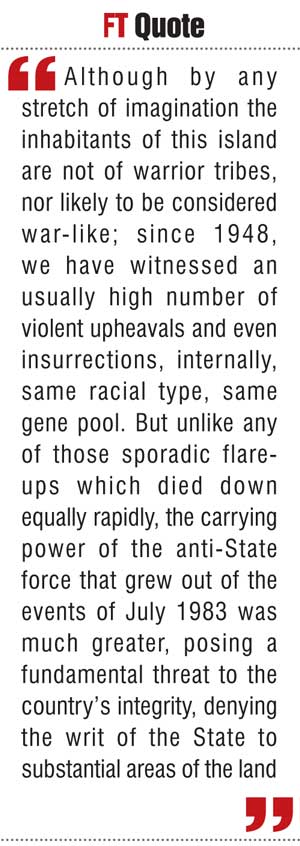

Although by any stretch of imagination the inhabitants of this island are not of warrior tribes, nor likely to be considered war-like; since 1948, we have witnessed an usually high number of violent upheavals and even insurrections, internally, same racial type, same gene pool. But unlike any of those sporadic flare-ups which died down equally rapidly, the carrying power of the anti-State force that grew out of the events of July 1983 was much greater, posing a fundamental threat to the country’s integrity, denying the writ of the State to substantial areas of the land.

What began with isolated acts of violence by a tiny group of militant youth and routine police actions to nab the offenders, eventually, and mainly after July 1983, grew into a full-scale war with an entrenched terrorist army. In 1977, power-drunk politicians, insensitive to the grievances of a sizeable minority, dared “if they want war they can have war”.

But these were not wartime leaders. When the war started in earnest the very same politicians ran around like headless chicken, rank amateurs out of their depth in the choppy waters of a brutal civil conflict. It was not a problem that could be solved by the accustomed obfuscations, threats, posturing or ponderous moralising.

No nation can go through three decades of such insecurity and violence without scars and damage. During those harrowing years, chaos, destruction, unpredictability, civil restrictions and even sudden death were the standard features of our lives. The so-called National Identity Card became a near appendage to a person, without which he dare not step out of his house.

Every Sri Lankan when applying for a visa to travel overseas came to be viewed as a person whose protestations were worthless, lacking in any credibility, and potentially a political/economic refugee. When your own Government does not trust you one bit, and demands so much authentication and form filling for every little thing, why would we trust you with a visa to our country, was the attitude of many embassies.

Naturally, the most affected community of the conflagration was the Tamils. The areas where they predominate, the north and the east of the country, were devastated by the fighting. It is not only property that were damaged, but more crucially, the social structure of that community turned completely topsy-turvy.

Until 1977, the Tamil leadership unfailingly comprised of learned men, mainly professionals. They were a very traditional society, deeply attached to their culture and faith. With the rise of the armed bands, a different leadership, a complete contrast in attitude and background, came to the fore. Even among those with a claim to an education, a crass mercantilism dominates now.

During the long years of conflict a very large number of Tamils, generally the more educated, migrated to mainly Western countries. They have prospered in the new environment and their support has helped those left behind immensely to maintain a reasonable standard of living. But as these new immigrants in the rich countries assimilate with the adopted culture, their ties with the land of origin are bound to weaken.

For the State, the terror tactics of the LTTE posed a challenge of unusual scope and complexity. In attempting to caulk the gaps in the much-needed security net, huge investments were made in men and material. A not-so-warlike people, in fighting a war created only by the incompetence of their own politics, were pushed to a war like posture in almost every sphere of activity.

As a percentage, the number of those in uniform now; forces, police, security guards, body guards and so on would be substantial. These are the best of our youth, able bodied and capable. They are not in any economic activity or value adding service but are in what could be broadly described as providing security. Some times when you prepare too much for a war, you may end up having your wish (again), and that will be terrible for a country like this.

The Provincial Governments set up country wide were a desperate attempt at appeasing the perceived demands of the militant groups. In reality these have only added to the already cumbersome bureaucracy and the corruption of the officialdom. In relation to larger countries, our provincial entities are tiny, and run on small budgets. Each Provincial Government has important sounding offices such as Governor, Chief Minister and subject ministers, apart from the additional bureaucracy. In our protocol-burdened culture, these are heavy loads to add. When being considered for high appointments in the Provincial Councils, being a voodoo culturist or an astrologer seems a much-desired qualification.

Another most appalling by-product of the war has been the provision of bodyguards for the politicians and the convoys that accompany them. Apart from the mediocre results of their efforts, it is commonly observed that a very high percentage of our politicians abuse power, live off the State, make money in irregular ways, indulge in blatant nepotism and sometimes even collaborate in criminal activity. To provide security to them at the taxpayers’ expense, with a bodyguard constituted of disciplined, law-abiding young soldiers, is to mock the very idea of legitimacy.

It is not only the Tamils who migrated in the last 30 years. Many Sinhalese, and again, the more cosmopolitan, frustrated with life in an endlessly war-torn country, looked for greener pastures. Having seen a larger world, very different ways of thinking, better standards; they may now baulk at coming back to the uncertainties, dilapidations and the deprivations they left behind. There is little in the present political firmament to give them hope.

While we were waging war for 30 years, neighbouring countries of roughly comparable economies such as Malaysia and Thailand, to take an example, have been steadily moving forward. They have advanced to such a degree today that it is most unlikely that a Thai or a Malay would marvel at a highway or a shopping complex as definitive proofs of development. These are now very standard features of their infrastructure. They are as commonplace as electricity or pipe-borne water.

Clearly, the aftermath of July 1983 has been disastrous for us as a country. Although the war has ended now, the causes as well as the creations thereof, political, social and even psychological forces that gave rise to it as well as arose during the long war, are still very much alive. Those who followed Prabakaran, the terrorist supremo, to their doom, ultimately believed in an absurdity, a utopia created with the gun. Equally, on the other side of the divide, the extremists who see it only in majoritarian terms, the jingoists who preach intolerance and bigots who want to take the country back to an imaginary past, are also absurdities, irrational, out of harmony with the rapidly evolving world today.

It is now more than 30 years since that fateful July of 1983.

During the following 30 years, we became known as a troubled country, with dim prospects. These were troubles of our own creation; grotesque, misshapen yet unique, a product of a certain history, a particular way of thinking. What one may consider most reasonable, another may view as an absurdity. Only time can tell which is which. But, as much as we would like to think otherwise, it is still uncertain that despite all the lessons of recent history we have stopped believing in absurdities.

And that uncertainty is most troubling.