Friday Feb 20, 2026

Friday Feb 20, 2026

Tuesday, 31 January 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Much of what passes for discourse in Sri Lanka is labelling. Call somebody a neo-liberal or a Marxist and you’re done. It’s lazy and it does little to advance understanding, arrive at good policy solutions or even bring the discussants closer to agreement.

I’ve been called a liberal as well as a neo-liberal, more or less at the same time. I have yet to figure what value is added by this practice other than enabling the labeller to avoid engaging with substance.

Futility of labelling

These days, some colleagues who have the good of the country at heart have taken up arms against the entering into Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) in the port sector on the ground that such policies are neo-liberal.

The labelling route is easy. The Government announces it is entering into an agreement with China Merchants Port Holdings. It is wrong and has to be opposed because such actions are neo-liberal. No concrete solution is offered for the problem of an under-utilised port built with loans that have to be paid back. No alternative is suggested for how the additional capital necessary to make Hambantota a profitable port is to be obtained other than through high-interest loans.

If pushed, the labellers will say the port should be managed by the Sri Lanka Port Authority and that, at most, a terminal should be given on a short-term lease to a private entity. In 1979, the SLPA was a significant innovation which contributed to Colombo becoming the most efficient port in the South Asian region. But what worked in the 1980s is not necessarily going to work now. The world has changed and our policy solutions must change accordingly.

If not for the efforts of people like Thilan Wijesinghe and the leadership of former President Kumaratunga in the late 1990s, the increasingly sclerotic SLPA may have led to Colombo losing its hub status. Today, it is living off the income received from its tenants, the South Asia Gateway Terminals (SAGT) and the Colombo International Container Terminals (CICT). It was in charge of all operations in Hambantota since 2010 and could not make it viable. But thanks to the construction of the deep-water facility and competition among three container operators, the Port of Colombo is flourishing.

In 2015, Colombo Port handled 5.18 million TEUs, up from 4.907 TEUs in 2014. Though volumes at SLPA terminals dropped to 2.25 million TEUs and at SAGT to 1.37 million TEUs, they increased overall because CICT handled 1.56 million TEUs. In 2015, there was a steep decline in Indian export trade, but Colombo’s volumes were not affected as in earlier years.

Even leaving aside the question of where the money for the needed improvements will come from, the track record of SLPA and changes in the world shipping market do not support the conclusion that the SLPA can make Hambantota a success. If the answer is not the SLPA, it has to be a private entity, locally owned (like SAGT) or foreign owned (like CICT). Should such a conclusion be excluded, because it is neo-liberal?

Is it not better to go through an evidence-based process of reasoning to arrive at the same conclusion that the government did when entering into a public-private partnership with CICT in 2013 (under one political dispensation) and with China Merchant in 2016 (under another political dispensation)?

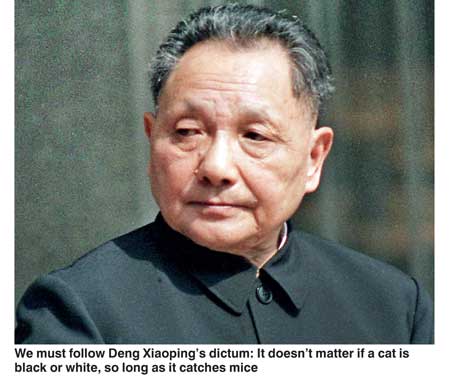

There is little value in labelling. What must be asked is whether it is the best solution when compared to the alternatives available at that particular moment. In other words, we must follow Deng Xiaoping’s dictum: It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.

If we avoid the lazy path of labelling, we will have to do more work such as actually assessing the relative merits of the available options. Once a solution has been selected, even more work is required to ensure that the legal agreements defining the roles of the government and the private entity are drafted well and to ensure that the required regulatory and enforcement mechanisms are put in place. Here again, knee-jerk objections to foreign consultants are lazy and counter-productive.

Depending on the task, the Government of Sri Lanka will save money by hiring expensive foreign consultants. What matters is not what one pays for technical expertise, but what one gets from the transaction. The previous Government spent Rs. 1 million for the feasibility study of Mattala Airport. Any half-decent feasibility study conducted by a foreign consultant would been 100 times that. The multi-million rupee savings achieved by that decision pale into insignificance in the face of the continuing losses that have been and will continue to be caused by the poorly-designed airport.

Has Deng Xiaoping’s approach worked?

In the same way, many Sri Lankan intellectuals consider trade liberalisation to be neo-liberal and therefore haram. But let us see what the leader of China said in his recent speech at Davos, a veritable den of neo-liberalism:

There was a time when China also had doubts about economic globalisation, and was not sure whether it should join the World Trade Organization. But we came to the conclusion that integration into the global economy is a historical trend. To grow its economy, China must have the courage to swim in the vast ocean of the global market. If one is always afraid of bracing the storm and exploring the new world, he will sooner or later get drowned in the ocean. Therefore, China took a brave step to embrace the global market. We have had our fair share of choking in the water and encountered whirlpools and choppy waves, but we have learned how to swim in this process. It has proved to be a right strategic choice.

And here is what he claims his country to have achieved with these “neo-liberal” policies:

Since it launched reform and opening-up, China has attracted over $ 1.7 trillion of foreign investment and made over $ 1.2 trillion of direct outbound investment, making huge contribution to global economic development. In the years following the outbreak of the international financial crisis, China contributed to over 30% of global growth every year on average…

China’s development is an opportunity for the world; China has not only benefited from economic globalisation but also contributed to it. Rapid growth in China has been a sustained, powerful engine for global economic stability and expansion. The inter-connected development of China and a large number of other countries has made the world economy more balanced. China’s remarkable achievement in poverty reduction has contributed to more inclusive global growth. And China’s continuous progress in reform and opening-up has lent much momentum to an open world economy.

So it seems that Deng Xiaoping’s economic policies have actually worked. The cat has caught mice. This is in contrast to the state-centric policies espoused by the exponents of labelling.