Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Wednesday Feb 18, 2026

Friday, 3 March 2017 00:00 - - {{hitsCtrl.values.hits}}

Two prominent gatekeepers of higher education in Sri Lanka are the University Grants Commission (UGC) and the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC). They have achieved this status due to an artificially created scarcity of credentials, or access to credentials, that they ‘guard’.

Two prominent gatekeepers of higher education in Sri Lanka are the University Grants Commission (UGC) and the Sri Lanka Medical Council (SLMC). They have achieved this status due to an artificially created scarcity of credentials, or access to credentials, that they ‘guard’.

UGC is the gatekeeper to the free-of-charge higher education offered by the public sector. These opportunities are limited to 20,000 or so entrants, or 4% of a given youth cohort, in any year. UGC seemingly does nothing but change the deck chairs on this public higher education ship as hundreds of thousands of other youth are left to navigate private options on their own.

Sri Lanka Medical Council or SLMC stands between the medical graduates and the medical profession on one hand, and the medical professionals and the general public on the other hand. Judging by its recent actions, the council guards the interests of medical professionals to limit the supply of doctors, while thousands of would-be medical students are struggling to find alternative educational paths, and patients suffer for lack of doctors. In contrast, professional bodies representing architects, engineers and accountants have expanded opportunities for higher education in their fields offering or facilitating non-State options.

The Minister for Higher Education in consultation with the UGC is empowered to give degree awarding status to qualifying institutions. It should be noted that S.B. Dissanayake, then Minister for Higher Education, for all his high-handed ways, was instrumental in following the procedures to open the doors to South Asian Institute of Technology and Medicine (SAITM) and NSBM as institutes awarding local degrees, increasing local degree opportunities vastly. UGC has been and continues to be more or less a bystander when it comes developing the higher education sector outside of the public university sector.

If UGC has been playing a lethargic role in the higher education sector in general, the SLMC has been playing an outright reactionary role, harming the growth of the medical sector. SLMC granted recognition to the medical degree program at the Kotelawala Defence University (KDU), literally at the point of a gun, but has put obstacles to a private initiative by Dr. Neville Fernando, acquiescing to trade union demands of the doctors.

As the Court of Appeals of Sri Lanka in its court order CA/WRIT/187/2016 (see: http://www.educationforum.lk/wp-content/uploads/2005/08/SAITM_ca_writ_187_16_2017.pdf) said, the Court does not have sufficient evidence to judge whether SLMC acted mala-fide or in bad faith, but the Court took note of the fact that SLMC investigators’ recommendation to not recognise SAITM graduates does not correspond with their detailed observations about the program, and that SLMC investigators have applied two different standards when holding investigations at SAITM and KDU, respectively.

Why are our higher education gatekeepers acting with duplicity or failing to serve a larger public interest? My guess is that it is because they are structured as ‘closed shops’ and hence destined to act in self-interest. In this column, I compare UGC and SLMC with parallel institutions the UK to make the argument that we urgently need legislation to open up the local counterparts to positive influences form outside.

Accountability in higher education presents more difficulties than primary or secondary education. Universities are on the top of the  credentialing hierarchy in a country. It is particularly difficult to assess quality in arts and science fields where there are no counter-balancing professional associations outside of the academia that could accredit the programs.

credentialing hierarchy in a country. It is particularly difficult to assess quality in arts and science fields where there are no counter-balancing professional associations outside of the academia that could accredit the programs.

An individual faculty member in arts or science may decide the flavour of a course offered, if not its full content; teach the course; and set and grade exams. Some forms of moderating or cross-checking procedures are usually available, but implementation can vary.

The decision to award a degree is often made within the confines of a small department. Whether in arts, science or professional fields it is difficult to judge from outside whether university teachers are up to date in their knowledge and their teaching is relevant to the needs of the economy and society.

In the Western world where universities have had a long history going back to the eleventh century, accountability has been built on reputations established over long periods of time. Overtime, as the state began to play a larger role in funding these institutions, the boards of governance in these institutions have been constituted to make them more participatory and hence more accountable and connected to ground realities.

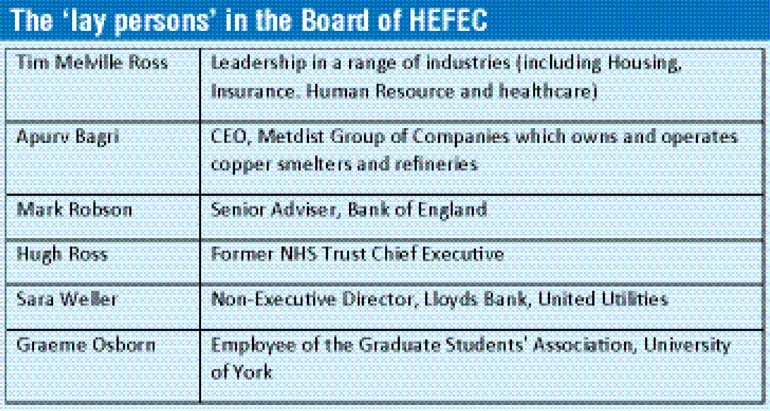

For example, the governing board of the Higher Education Funding Commission of England (HEFCE) is appointed by the Minister for Education to include six non-academics or ‘lay persons’ in addition to four academics as board members. While the academic members are those with solid academic credentials, the non-academic members or lay members have been selected such that they bring depth and breadth of experience in industries from healthcare to mining.

The public sector is the first choice in higher education for the average family in Sri Lanka. Private higher education is growing, but it will not make a dent in the demand for higher education by these families. Besides being free-of-charge, the public higher education sector offers a zone of comfort and familiarity for the average Sri Lankan youth.

Sadly, the public sector has failed to equip their students with the knowledge and skills necessary to face competition from local elites for attractive jobs outside of government. One reason for this failure is that the public university teachers themselves lack the necessary knowledge and skills.

Most public university teachers try to keep the ugly truths about our public sector under wraps, but a few dedicated individuals like Professor Sunethra Weerakoon of Sri Jayewardenepura (See ‘Institutional and cultural corruption within public universities’ – http://www.educationforum.lk/wp-content/uploads/2005/08/USJP_Symposium_2016_Sunethra_E.pdf) and Dr. Predeep De Silva of Ragama Medical Faculty (See Lankadeepa, 14 February, p. 4) have taken the initiative to discuss problems in the open, and provide constructive suggestions for improvement.

A few dedicated academics can do little unless the regulatory authorities are structured to bring external actors into the sector. Currently, the only outside actor in the University Grants Commission is the ex-officio representative from the Treasury. Six of the other seven members are all academics who have risen through the ranks in the public university sector. Dr. Wickrema Weerasooriya is the only other academic with a broader range of experiences.

In regard to the regulation of the medical profession in UK, the country’s General Medical Council is made up of 12 members, with half of them required to be lay persons or those outside of the medical profession. The lay persons in the present GMC include four individuals who have received public ‘decorations’ of Dame, Baroness, etc. for services in the public or voluntary sectors and two others with expertise in finance and actuary, respectively. The Management team of the GMC also brings together a wide range management talent, and, notably none them have medical qualifications. Appointments to the GMC are not without controversy. According Metro newspaper of UK:

“It’s just been announced that Charlie Massey will be the next CEO of the General Medical Council, an independent body set up to regulate doctors. Massey, however, is currently a director general at the Department of Health and advisor to Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt – which a lot of medics think is a little too close for comfort.”

Further, in a letter to the British Medical Journal of BMJ, an individual who is probably a doctor, has raised the issue whether Charles Massey, the new CEO of GMC has an academic qualifications and, if not, whether that is appropriate. Though such concerns are valid, the existence of a balance of academics and non-academics in the council gives it a balance of political influences v. professional self-interest.

The 25-member of the council of SLMC is exclusively made up representatives from medical profession. First, the eight deans of the seven public medical schools and dean of Faculty of Dentistry are members. It is probably a good reason why these faculties do not receive the same scrutiny as faculty of medicine at SAITM.

Of the 10 Members to be elected from the medical professions, eight of them represent doctors, one represents apothecaries, and another one represents the dentists. The Director General of Health, who is also a doctor by convention, serves as an ex-officio member. The Minister for Health can nominate the six other members including the Chairman, but all nominations have been restricted, voluntarily or otherwise, to medical professionals. The result is a Medical Council which cannot be distinguished from a trade union of medical professionals and/or the public medical education monopoly.

(The writer can be reached via [email protected].)